Siliconpolitik: Ab Dilli Door Nahin

— Pranay Kotasthane

Readers would've noticed that this newsletter bats for a Quad partnership on semiconductor supply chain security for geopolitical, geoeconomic, and technological reasons.

In edition #5, we proposed what an 'announcement' on semiconductors as an outcome of the upcoming Quad leaders-level summit meeting, could look like. We wrote:

One, announce a Quad Semiconductor Supply Chain Resilience Fund. Think of this as a multi-sovereign wealth fund but for semiconductor investments across the Quad countries. This fund could focus on two areas:

create a roadmap for new manufacturing facilities across the Quad countries. One of the focus areas should be to secure supplies not just at the leading-edge nodes but also at key trailing-edge nodes, which will continue to remain workhorses for automotive, communications (5G), and AI.

Sponsor new standard developments such as composite semiconductors and create one centre for excellence in each Quad country in an area of its immediate interest. For example, Australia could host the CoE for new materials in electronics, Japan could host the CoE for silicon manufacturing equipment, while the US and India could host CoEs on specific fabless design architectures.

Two, and this one is an even more ambitious goal, facilitate strategic alliances between companies in the four quad states.

So, we were glad to read Asia Nikkei's report claiming that a draft joint statement of the Quad summit seems to have identified semiconductors and 5G as two areas for technology collaboration.

From an Indian national interest perspective, this collaboration should be used to get a semiconductor fab up and running, although at a matured node such as 65 nm. This move would minimise the risk of failures while ensuring India's core defence and strategic interests are secured.

The AUKUS defence alliance has shown that the US is willing to share sensitive technologies with key partners, something it wasn't amenable to in the past. This new technology alliance mindset should become the norm in the Quad as well. India should push for the US to lower investment barriers and reduce export controls so that companies such as a rejuvenated Intel can consider setting up mature-node fabs in India, Japan, or Australia. The geopolitical timing couldn't have been better.

We're keeping an eye on the Quad Summit. There will be another edition discussing the specific announcements on technology collaboration.

Meanwhile, for a detailed take on a Quad partnership on semiconductors, read my paper here.

If you are looking for a primer on semiconductor geopolitics, here's a recording of a session I participated in, for Ahmedabad University.

Antriksh Matters #1: Where’s India’s Space Doctrine?

- Aditya Ramanathan

In the last few years, India has set up a tri-services Defence Space Agency to manage its military space capabilities. It has greenlighted the setting up of a Defence Space Research Agency that is to be “entrusted with the task of creating space warfare weapon systems and technologies". It has also engaged in dialogue with the US, Japan, and France on space security and has sought to increase its space situational awareness (SSA) capabilities, which are crucial to ensuring the safety of space-based assets.

While these efforts are modest, they are likely to expand in the near future. What remains to be developed (at least in the public domain) is a doctrine that lays down the rationale for military space capabilities, and provides signposts for those crafting strategy or planning acquisitions.

We at Takshashila took inspiration from India’s 1999 Draft Nuclear Doctrine, and put together a succinct, five-page “A Space Doctrine for India”, following many hours of debate and discussion.

The doctrine, as we envisaged it, would be anchored in deterrence but would be flexible enough to keep India’s options open. The key objective would be to preserve India’s use of space. India’s space forces, which are meant to protect its use of space would be:

Versatile, encompassing a range of Earth and space-based non-kinetic and kinetic capabilities.

Vigilant, providing early warning of imminent attacks or identifying and attributing attacks already underway, whether during peacetime, crisis or conflict.

Effective at taking defensive and offensive countermeasures against imminent or ongoing attacks on Indian space assets or forces.

India’s terrestrial forces would also form a key component of the space doctrine since they would need to be capable of functioning in a space-degraded environment. They would also have to train to perform in such conditions and develop terrestrial back-ups for space-based capabilities that are vulnerable to enemy attack.

Our doctrine also laid out the role of command and control, and India’s objectives in pursuing arms control agreements or restraint regimes.

In a separate document, Space as a Geopolitical Environment, we sought to make explicit the assumptions that had gone into the making of the doctrine. Drawing on our discussions, as well as the works of scholars such as Bleddyn Bowen and John J. Klein, we brought it down to ten points:

1. The geography of space is determined primarily by gravitational forces and radiation.

2. Space is a distinct environment. The character of orbital space fundamentally differs from that of Earth’s stratosphere, troposphere, and so-called ‘near space’. Therefore, space power cannot be extrapolated from the military term ‘air power’.

3. Human activity in orbital space is shaped by the interaction between activities on Earth and the physical character of the celestial littoral, as defined by such phenomena as orbital mechanics and solar weather patterns.

4. Human activity in orbital space is heavily Earth-centric, with most orbital craft tasked with providing remote-sensing, communications, and navigation services on Earth.

5. Space power is the ability of a state to leverage its space-related activities to wield influence in international politics. It encompasses commercial, military and scientific activity in space, as well as all Earth-based activities connected to the use of space.

6. Celestial lines of communication (CLOCs) are the routes used for space-related activities, including orbital paths and communications links between satellites and Earth.

7. The command of space is the ability to use space, deny it to others, or to do both.

8. Space warfare is waged for the command of space. It can be waged both in space and on Earth.

9. Orbital space has always been militarised, but new technologies and the diffusion of existing technologies will make it easier to contest the use of space in the near future.

10. The battlefield of space is characterised by vast distances, the lack of natural cover and concealment, the absence of atmospheric attenuation, the presence of radiation, and the mechanics of gravitation.

If you enjoy this newsletter, please consider taking our special credit courses in Ethical Reasoning in Public Policy and Evidence-based policy-making for responding to COVID-19

Cyberpolitik:(un)Safe Harbour

- Sapni G K

The past couple of days have seen a lot of high-profile media coverage of Facebook. A few of them stand out for their arbitrariness in decision-making. The Wall Street Journal reported that Facebook favoured profitability over a finding that Instagram causes body dysmorphia in one out of five teenage girls who are users of the app. Another report suggests that Facebook followed a differential treatment for select users, not taking down content that was otherwise in violation of its community standards.

Such reports of devious practices add to the bid against safe harbour protection given to social media platforms that host user-generated content. Governments across the globe use these incidents to justify restrictive and harmful mandates on speech on these platforms. The Brazilian Supreme Court and Congress acted steadfastly against a recent ban on the removal of election-related disinformation promulgated by the Bolsonaro Government. The US state of Texas also passed a law preventing content-takedown to “protect the freedoms of conservative users." China’s recent recommendation algorithm regulations, which we covered in the previous edition, also undermine safe harbour protections in the interest of toeing the line drawn by those in power.

Safe harbour provisions have been the backbone of the development of social media platforms. They protect social media platforms from liability for user-generated content. They catalysed a new wave of ideas around the governance of these particularly positioned privately-owned public spaces. The provisions opened up new avenues for governance such as large-scale pre-legislative policy consultations.

Cyberspace - particularly the internet public sphere created by social media platforms - acted as soft power tools for countries. Russian content farms arguably meddled with the elections in the USA. However, social media popularised K-Pop culture, as it was exported across the globe giving South Korea a niche area of cultural dominance. More broadly, social media platforms also contributed to the rise of new identities.

Barlow’s Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace might be an unachievable utopia today, but social media contributed massively to a stronger sense of community in people located wide and far. Politically motivated actors maliciously meddling with safe harbour protections will not augur well for the future of cyberspace that is already inching closer to a splinternet. The shifting narratives can cause changes in the undercurrents of power in the frontier of cyberspace.

Techpolitik: After-effects of Nokia Suspending O-RAN Alliance Participation

- Arjun Gargeyas

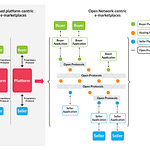

In 2018, a group of telecommunication firms and network operators came together to improve the coverage of radio access networks (RANs) across the globe. A proposal to transition into virtualized network elements and open interfaces to the RAN was the idea behind improving global connectivity systems through radio communications.

The O-RAN Alliance was conceived in the hope of providing a better platform and enhancing opportunities for small and medium-scale firms in the communications domain. This includes networking software, hardware supply and cloud computing firms collaborating to create an open and programmable RAN solution that can be deployed. Other O-RAN Alliance initiatives have focused on incorporating artificial intelligence (AI), specifying interfaces and APIs to drive appropriate standardization, and establishing the supply chain infrastructure.

The organisation is involved in defining and creating specifications for open interfaces and functions used in open radio access network architecture. Currently, the group has a total of 29 operators including telecommunication giants like AT&T and China Mobile. O-RAN specifications adhere to specific standards such as the ones created by global standard-setting bodies like 3GPP for 4G and 5G standards.

Founding operator members include AT&T, China Mobile, Deutsche Telekom, NTT DoCoMo and Orange. The O-RAN ecosystem allows for newer and smaller entrants focused on specific interoperable solutions for 4G and 5G to be included in the system. This mainly allows for mixing and matching different hardware and software solutions created by multiple vendors.

Nokia, one of the earliest champions of the O-RAN alliance, recently announced their temporary suspension of work on the O-RAN system. This was in response to the US government taking cognizance of Chinese firms’ activities and blacklisting them. A number of restrictions were placed on some of the Chinese vendors, part of the alliance, by the US authorities citing threats to national security.

Nokia officials mentioned that the smooth functioning of the alliance needs the support of Chinese vendors, who form a fifth of all the members of the alliance. Some of these Chinese companies, which are part of the O-RAN alliance, were added to the Entity List of the US, which serves as the list of all blacklisted companies in the country. Nokia has categorically said that these firms hold considerable clout in the industry and cannot be ignored.

This has put the objective of the O-RAN alliance becoming the next global standard for communications operations in a limbo. It is not known if Nokia will eventually pull out of the alliance or continue to work without the involvement of blacklisted Chinese firms.

This can also mean that there might be parallel development of O-RAN technology both by the alliance and other Chinese firms, which goes against the tenet of the technology being an international standard facilitating interoperability between different vendors. Some operators and vendors are pushing ahead on Open RAN irrespective of the status of activities at the O-RAN Alliance.

Heads of technology companies believe that if the O-RAN alliance is accorded the status of an international standards body, which has a considerable global reach, then the frictions between the members of the alliance and a single government will not result in the breakdown of the entire group. The whole point of the O-RAN alliance is to break the oligopolistic telecommunications market by providing opportunities for smaller firms to succeed in this space. Political nitpicking is going to derail that effort and ensure that dependencies still exist.

Antriksh Matters #2: Russia Seeks a Favourable Anti-counter Space Future

- Aditya Pareek

Weaponisation in space is a major concern that has become increasingly important to the global arms control discourse. The advantages of basing weapons systems in space are hardly lost on major world powers. The same also goes for their anxieties about similar capabilities wielded by adversaries.

Russia has been curiously signing joint statements on the non-placement of first weapons in space (NPOK) with countries that don’t have any counter space capabilities. According to this BBC Russian Service report, which also has a nice rundown of the matter, Russia has signed such agreements with

“Venezuela, Cambodia, Togo, Uruguay, Burundi and a dozen other countries”.

While this Kommersant report mentions that Russia has

“accumulated 25 such interstate joint statements. And there is also a multilateral one - within the framework of the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO)”

According to this brief on the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, which makes it clear that, although closely related to similar multilateral initiatives introduced via the Conference on Disarmament, NPOK is a unilateral Russian initiative.

As the Kommersant article argues, the pragmatic purpose of signing these agreements is to have leverage in multilateral fora where Russia can count on the signatory nations’ support on counter space and anti-counter space agreements that may address its concerns and keep its shared interests with these nations in mind.

Our Reading Menu

[Research Article] The capricious relationship between technology and democracy: Analyzing public policy discussions in the UK and US by Bridget Barrett, Katharine Dommett and Daniel Kreis

[Facebook Files] An investigation by the Wall Street Journal

[Book] The Routledge Companion to the Makers of Global Business

[Commentary] Geopolitics and Technology – US‑China Competition: The Coming Decoupling?

[Book] Undersea Geopolitics: Sealab, Science, and the Cold War

Book by Rachael Squire