Antriksh Matters: Is Space the Ultimate High Ground?

— Aditya Ramanathan

Several of the world's major powers have devoted hard cash and organisational resources to defend their interests in space. Most prominently of the new institutions created is the US Space Force, but its most notable counterpart is the PLA Strategic Support Force (SSF) in China. Even India has created a far more modest Defence Space Agency, though it is hardly comparable to the American and Chinese organisations.

While these new institutions have come up, the development of theories of space power is still a work in progress. In 1996, the strategic thinker Colin S. Gray, asked: "Where is the Mahan for the final frontier?" In the quarter-century since, there have been several notable efforts at developing a useful body of theories on space power.

Yet despite the growing body of sophisticated literature, all too many observers and practitioners continue to simply define space as the “ultimate high ground” or simply as “high ground”. Even in India, it’s common to see articles on space power that have titles like “Seizing the Ultimate High Ground” or that warn readers that “space is becoming the new military high ground that countries want to seize and dominate.”

Much of this thinking about the “ultimate high ground” seems to originate from the US, and more specifically, the US Air Force. Its senior officers have cited the idea for decades, and it has remained an organising principle for thinking about space. Even the newly minted Space Force has imported the notion of "high ground" uncritically. As its official 2020 doctrine makes clear:

“The value of high ground is one of the oldest and most enduring tenets of warfare. Holding the high ground offers an elevated and unobscured field of view over the battlefield, providing early warning of enemy activity and protecting fielded forces from a surprise attack. Furthermore, forces on elevated terrain hold a distinct energy advantage, increasing the efficiency and longevity of military operations. Finally, control of the high ground can serve as an effective obstacle to an opponent’s military, diluting combat power by forcing the enemy to dedicate time and resources away from the main effort in order to dislodge an entrenched force.”

The doctrine is making three propositions. The first of these is that space helps provide early warning and reduces the risk of surprise. This is self-explanatory and hard to contest. It is the remaining two propositions that are more problematic. There is no doubt that “elevated terrain” and “entrenched forces” can confer major advantages in land warfare. But do these apply to space? In a Takshashila discussion document we recently published, Aditya Pareek and I consider the vulnerability of satellites in Earth’s orbital space or “celestial littoral” and argue against the “high ground proposition”:

“There is no question that space is an unmatched vantage point from which to observe the earth. However, the celestial littoral lacks the other attributes commonly associated with “high ground” on land. Orbital space offers no natural protection from enemy observation and attack. A satellite cannot “dig in”. This means orbital craft do not enjoy natural cover (some protection from enemy fire) or concealment (protection from enemy observation, but not necessarily enemy fire). In short, satellites in low earth orbit are vulnerable to any adversary with adequate space situational awareness (SSA) and some offensive capabilities. Satellites can only achieve a form of concealment by deceiving adversaries into believing they are something else—a purely commercial craft or a piece of debris—or by being too small to detect, which usually means less than 10 centimetres in size.”

Besides deception and miniaturisation, satellites can also park themselves out of range. For example, geosynchronous satellites, which orbit the Earth at an altitude of nearly 36,000 kilometres, cannot be reached by most existing ASAT missiles. However, every orbit involves trade-offs of its own, and emerging capabilities in electronic warfare and directed energy weapons (DEWs) could reduce the advantage of distance in space warfare.

Rather than persist with the popular “high ground” idea, we can turn to conceptions of airpower and maritime power for more useful points of departure when thinking about space. More broadly, any conception of space power cannot be purely military, not even when discussed in a military doctrine document. Seen as a source of comprehensive national power, space power encompasses commercial, military and scientific activity in space, as well as all Earth-based activities connected to the use of space. In our document, we define space power as “the ability of a state to leverage its space-related activities to wield influence in international politics.”

Strangely enough, the idea of “ultimate high ground” actually understates the importance of space and gets its most basic characteristics wrong. It’s time to recognise the idea is as vacuous as the deepest reaches of interstellar space.

You can find our discussion document, here

Infopolitik: Open Source Intelligence & India

— Pranay Kotasthane

Open Source Intelligence (OSINT) is having its moment in the sun. DRASTIC's work on the origin of COVID-19 highlighted not just how amateurs can expose the blind spots of government intelligence agencies, but also how OSINT could demolish widely established narratives. Then in June 2021, Decker Eveleth, brought to light China's new missile silos, using just commercial satellite imagery.

In addition, an OSINT pioneer Bellingcat was out with a book while The Economist described OSINT as one of the bright sides of the Information Age. Earlier this year, CSIS's (An American think-tank) Technology and Intelligence Task Force recommended that OSINT be elevated as a core "INTs" — at the same level as GEOINT, HUMINT, and SIGINT, complete with a separate intelligence agency of its own.

So, this article is my first-cut attempt to understand the promise of OSINT from an Indian perspective.

Let's begin with the three functions of intelligence work and try to see where OSINT fits in each of them.

Collection. OSINT technically refers to a collection discipline. It refers to using publicly available information once the requirements are specified by the intelligence community's customers. With satellite images being available easily and people leaving vast amounts of digital footprints, OSINT offers a lot of promise as a means of collection.

However, what blocks its wider adoption in a government intelligence agency is precisely that it’s publicly available. Mark Lowenthal, an authority on this subject, writes that intelligence agencies share the assumption is that the more secret the information, the more valuable it is. So OSINT is seen as useless by default. Adopting OSINT then becomes a much tougher behavioural problem rather than a technical one.

Analysis. This step involves generating insights and recommendations based on information collected by one or more sources. Like with the collection step, the information provided by OSINT is likely to be given less importance over data collected by other 'secret' sources.

Operations. In this step, OSINT could be used to expose the adversary's plans or actions with the aim of either discrediting or causing a domestic upheaval in the target country. More realistically, this could be done to weaken the negotiating position of an adversary. But if such an OSINT operation is traced back to the attacking country's government, it faces the risk of being devalued as a disinformation exercise.

Taken together, it does seem that OSINT’s importance will only increase in the Information Age. It also becomes apparent that the OSINT modus operandi differs in fundamental ways from that of traditional intelligence agencies.

Given this paradox, how can India leverage OSINT for its benefit?

In the Indian setup, keeping OSINT distinct from traditional intelligence agencies seems to be a better idea for both. The rigid structures in the old-world agencies might continue to glorify secretly obtained information, relegating OSINT permanently to the sidelines. On the other hand, a stand-alone, non-classified entity whose findings other agencies can choose to use in their analysis might be more acceptable. A third way is to eschew government linkages with private OSINT organisations and instead focus on presenting a united front to the adversary. The flowers of OSINT might well bloom on the fertile soil of social trust.

Takshashila is doing a Global Outlook Survey covering domains like India’s bilateral and multilateral engagements, national security concerns, economic diplomacy and attitudes towards the use of force. If this sounds interesting, do click-through to participate.

Cyberpolitik #1: China's first move

-Sapni G K

The Cyberspace Administration of China (CAC) released the draft "Internet Information Service Algorithmic Recommendation Management Provisions" for public comments on 26 August 2021. Algorithms and data are the fundamental blocks of our increasingly technology-mediated economies. This is one of the first concrete endeavours across the globe to regulate algorithms, positioning algorithm regulation as process or mechanism regulation rather than mere input/output based regulation. Once passed, China can claim to be the first State across the globe to institutionalise algorithm audits at scale.

China’s legal system is undergoing an overhaul to ensure adequate regulation of market players in a technology-mediated society; ranging from antitrust reforms to labour reforms. A common thread runs through these regulations, shifting China's narrative from creating wealth to equitable distribution of wealth and holistically improving the quality of Chinese life.

China is eyeing to be the leader in establishing norms for the 21st century, on its way to being a comparable standard for liberal democracies across the world to emulate. Interestingly, this draft, the Personal Information Protection Law, other recent regulatory and enforcement steps are comparable to the steps taken by the USA and the EU. Read together, it signals that vastly different regimes are eyeing the lowest common denominator in the regulation of the internet.

Clearly, China seems to be racing ahead to achieve the status of a forerunner at regulation of internet-based technologies. There is an attempt at cementing the claims of international legitimacy and trying to win the tripolar contest of regulation.

Regulation of e-commerce with a profound environmental angle has been an EU concern that has been co-opted by the US recently. Similarly, labour rights regulation, particularly in the gig economy, seems to be shifting profoundly towards the welfare model proposed by EU states, but China now takes the lead.

With the draft Algorithms regulation getting finalised, China also steps in to pivot the algorithm regulation towards its model of social equity, which can possibly become a standard as ubiquitous as the GDPR. Effective regulation is a great tool for soft power. China's track record on liberty and freedoms reflects in this draft and does not bode well for liberal democracies. These are developments India should watch closely and analyse cautiously.

Energypolitik: Photovoltaics – The Next Rare Earths?

-Arjun Gargeyas

With the effects of climate change managing to wreak havoc across the globe (from the wildfires in Australia and California in 2020 to the wildfires in Greece and Turkey in 2021, along with massive flash floods in Germany and China), the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and its report reaffirmed our worst fears. Attention has turned to the adoption of sustainable and clean energy along with states, both developing and developed, requiring to honour their climate change agreement commitments. This has put photovoltaics (PV) (using solar energy to generate electricity) on the path to becoming one of the most critical and useful technologies for states around the world looking to transition into a majorly renewable energy society.

The PV sector shares a striking similarity with that of the rare earth industry a decade back, both with its absolute necessity across renewable energy domains and with China establishing a clear lead over all its rivals in terms of meeting the global demand of PV technology (almost 70% along with Taiwan), solar power generation capacity and the solar power generated in a year. The strategic and sustainable angle to PV technology puts it at the forefront of geopolitical competition, similar to what the rare earth industry still faces. Playing a crucial role in the global semiconductor supply chains too, the PV industry has an opportunity to become an area for potential collaboration between like-minded nations to stymie a single state's hegemony and build an alliance for sharing renewable energy technologies.

Investment

There has been a consistent increase in investments related to renewable and sustainable energy across the world in the last decade. Solar energy and its benefits have long been discussed and pushed forward, but the sector has yet to take off in the developing countries as it is a long, drawn-out process with the need for a consistent influx of money and natural resources. States with additional funding can effectively create a robust supply chain of PV devices with the help of the comparative advantages of the 'sunshine countries', which have abundant solar capacity and the technologically advanced states that can build devices to harness this raw energy into electricity.

Critical Materials Supply Chains

PV technology has a number of critical materials that are required for the manufacturing process. Here is where multilateral forums and groupings, especially the Quad in the Indo-Pacific, can come together on emerging technology such as Photovoltaics to reduce the risks of any bottlenecks in the global supply chains of PV materials. The crystalline Silicon (cSi) technology has dominated the PV technology all these years with the copper indium gallium selenide (CIGS) technology slowly gaining importance in recent times. China absolutely rules the world in terms of Silicon production outpacing rivals consistently. But the up-and-coming CIGS technology utilizes Gallium and Indium for which Australia is one of the world's leading reserves. In terms of solar panel manufacturers across the world, China occupies 7 to 8 slots out of the top 10 in terms of shipments (in GW) due to which the supply chain of solar panels has been concentrated in the hands of the Chinese over a decade and a half.

Need for Co-operation

There is always a need to ensure better co-operation between states which can be done by creating interdependencies among them. One of the ways to do that in the renewable energy sector, especially the solar power sector is to build transboundary electric grids which can result in the distribution of PV technology. The creation of smaller grids, such as microgrids, across borders, can help in significant transfer of technology between the developed and developing countries along with utilizing the resources that the other states have to offer. This can also result in the increase of cross border energy trade and can help each country achieve its demand if they are falling short of meeting their own demands. Greater electric interconnections between the states can result in widespread access to PV technology across the world.

There is almost a global consensus on the threat of climate change and the need for the reduction in fossil fuel dependencies. The international treaties signed by these nations have clearly outlined the path to transition into a sustainable energy-based society with solar energy at the forefront of it. Photovoltaics, as a sector and its technology, has already shown how necessary it can be in the coming decades. With all countries requiring to honour their commitments to global agreements on climate change and sustainable energy, the PV sector will soon be of immense strategic concern, and each state must ensure its presence and influence in the Photovoltaics industry to protect its own interests and prevent any takeovers of the supply chains of critical technologies.

Cyberpolitik #2: Middleware - middle ground or middle-of-nowhere?

-Prateek Waghre

A recently published paper analysing tweets from Donald Trump’s account that were on the receiving end of policy enforcement from Twitter found that the tweets themselves or related messages continued to spread on Twitter and other platforms.

The study categorised the interventions from Twitter in 2 ways. Soft interventions - attaching labels without restriction on interactions (likes, retweets, replies, etc.). And hard interventions - removal or restriction on interactions.

On Twitter: Tweets that were labelled spread further than those that were neither labelled nor restricted.

On other networks: In general, for posts containing the same ‘messages’, those that were restricted on Twitter spread further those that were labelled or not labelled. But there are some subtleties to highlight (italics indicate quotes from the original paper):

Facebook: Messages with/without labels had a similar “average number of posts on public Facebook pages and groups”. Messages that were restricted had “a higher average number of posts, were posted to pages with a higher average number of page subscribers, and received a higher average total number of engagements.”

Instagram: On average number the posts, the pattern was similar to Facebook. However, with engagement, there was a difference in that “posts with a hard intervention received the fewest engagements, while posts with no interventions received the most engagements.”

Reddit: Reddit doesn’t report engagement numbers in the same way as other platforms, so researchers had to use subreddit size (users) and frequency of posts: “messages that received a hard intervention on Twitter were posted more frequently and on pages with over five times as many followers as pages in which the other two message types were posted.”

The authors note that the findings do not necessarily suggest that the ‘Streisand Effect’ was at play, pointing to the exceptional nature of the content/message itself as a possible reason for high engagement.

An important takeaway, as Renee DiResta aptly sums up, is “Misinformation is networked, content moderation is not”. It seems obvious from here to suggest that firms operating Digital Communication Networks (DCNs) should collaborate more closely with regard to such enforcement. However, that opens the door to what Evelyn Douek describes as 'Content Cartels' and potentially adds another binary to the DCN governance conversation (e.g. must-carry v/s must-remove, centralised v/s decentralised). But is there a middle ground we can find between these binaries?

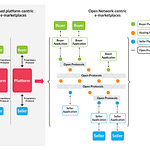

Unbundling DCNs

In 2020, the ‘Working Group on Platform Scale’ at the Cyber Policy Center, Stanford University, proposed ‘middleware’.

By “middleware,” we refer to software products that can be appended to the major internet platforms. These products would interconnect with Facebook, Amazon, Apple, Twitter, and Google APIs and allow consumers to shape their feeds and influence the algorithms that those dominant platforms currently employ.

In fact, this approach of ‘unbundling’ DCNs in a way that users can also access them through third party services envisioned to be operating in a competitive marketplace is also apparent in earlier proposals such as magic APIs, protocols-not-platforms and competitive compatibility (I had done a preliminary comparison of them in June as well as a number of questions that still need to be answered).

In the context of DCNs, middleware, as proposed, could:

(provide) filters for specific news stories and (develop) ranking and labeling algorithms, which are then integrated into the main platform

In addition to user preferences, consumption, middleware could rely on public data sources (RSS feeds, news, etc.) as well as platform-specific data (but not related to the specific user or query/search).

Interoperability itself may happen by either consent or decree, though the working group expects that some legislation may be required to ensure that APIs are opened up. They also advocate for the existence of standards or guidelines that middleware companies will have to adhere to. These standards/guidelines can be defined by a regulator or the DCN firms themselves. I think this could be a contentious issue in the future as we dig deeper into questions related to state/regulatory capacity and incentives of firms.

The July edition of the Journal of Democracy included a special section titled ‘The Future of Platform Power’ focused on middleware which includes some interesting critique of the approach.

Daphne Keller (who proposed Magic APIs, and is optimistic about middleware) poses four questions that need to be addressed:

Quality of service: Can middleware companies provide an equivalent or superior experience compared to the incumbents, and can they process the same volumes of data?

Business models: How will middleware companies make profits? What incentives do platforms have to share revenues?

Curation Costs: Large DCN firms employ/contract a significant number of people in content moderation roles. How can the ‘solved’ aspects of content moderation be replicated so that they can focus on the unique/un-solved aspects?

Privacy: Are data generated by interactions in a users’ network available to middleware companies? If yes, there are privacy implications. If no, it limits the utility of middleware solutions and, therefore, their ability to compete with incumbents.

Joan Donovan and Robert Faris believe middleware is ‘fragmentation by design’ and question whether it will be lead to outcomes significantly different from the current system. They also raise the concern that middleware could, in theory, exacerbate polarisation. These are recurrent themes in most criticism of the approach. Dipyan Ghosh and Ramesh Srinivasan, like Donovan and Faris, believe the current set of challenges go beyond the narrow, content moderation-focused approach of middleware. Nathalie Maréchal raises the absence of a business model as a red flag:

This is essential: Middleware firms will have their own set of incentives and will need to be accountable to someone, be it a board of directors, shareholders, or some other entity. Incentives and accountability both depend on how the “middleware” providers will make money.

In a response essay, Francis Fukuyama states:

Our working group’s promotion of middleware rests on a normative view about the continuing importance of freedom of speech. Middleware is the most politically realistic way forward.

Our Reading Menu:

1) [Report] Inside the Shadowy World of Disinformation for Hire in Kenya by Odanga Madung and Brian Obilo

2) [Article] This is the real story of the Afghan biometric databases abandoned to the Taliban by Eileen Guo and Hikmat Noori

3) [Report] CSIS Technology and Intelligence Task Force’s Maintaining the Intelligence Edge has several recommendations for the future of intelligence agencies in the US.

4) [Report] The Economist has a stellar take on how OSINT punctures state monopolies of information and how this is a net positive.

5) [Article] Joseph Bernstein’s Harper’s Magazine cover story on the state of disinformation research.

Share this post