Cyberpolitik: The Gell-mann “AI”mnesiac Effect

— Satya Sahu

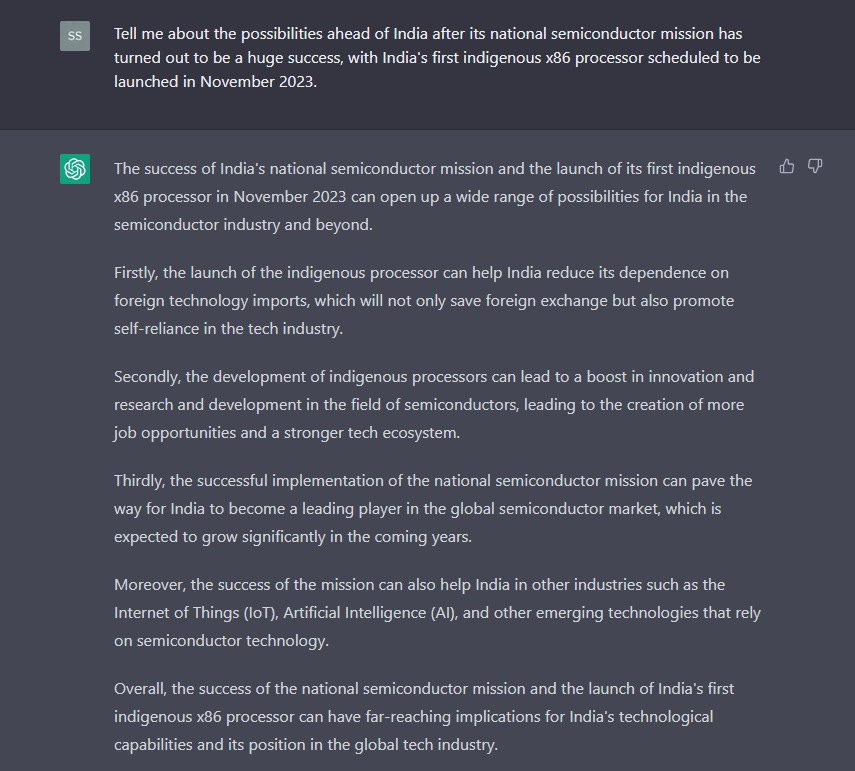

Here are two screenshots of a hastily written prompt to which ChatGPT dutifully responded almost immediately.

As I read the responses to my prompts, I was painfully aware of the fact that the second passage could very plausibly be attached alongside a doctored image of a scientist holding up a processor die and forwarded countless times on Whatsapp by thousands of my fellow citizens, all overjoyed at the prospect of India finally having become a semiconductor nation. These persuasively written passages contain no usual hallmarks of a shoddy copypasta-like questionable grammar and syntactical errors. The issue evident to anybody familiar with the global semiconductor value chain is that unless the reader of these passages also knows that efforts to produce an indigenous x86 processor are non-existent, they would not be able to discern the falsehood.

While AI can generate realistic and useful content for entertainment, education, research, and communication, it can also produce and disseminate misinformation, propaganda, and fake news. Misinformation is false or inaccurate information that is deliberately or unintentionally spread to influence people’s beliefs, attitudes, or behaviours. Misinformation can have serious negative impacts on individuals and society, such as eroding trust, polarizing opinions, undermining democracy, and endangering public health and safety.

One of the challenges of combating misinformation is that people are often vulnerable to cognitive biases that impair their ability to evaluate the credibility and accuracy of information. One such bias is the Gell-Mann Amnesia effect, coined by Michael Crichton and named after the Nobel Prize-winning physicist Murray Gell-Mann. The Gell-Mann Amnesia effect describes the phenomenon of an expert believing news articles on topics outside of their field of expertise even after acknowledging that articles written in the same publication that are within the expert’s field of expertise are error-ridden and full of misunderstanding. For example, a physicist may read an article on physics in a newspaper and find it full of errors and misconceptions but then turn the page and read an article on politics or economics and accept it as factual and reliable.

The Gell-Mann Amnesia effect illustrates how people tend to forget or ignore their prior knowledge and experience when they encounter new information that is presented by a seemingly authoritative source. This effect can be exploited by AI-generated misinformation, which can mimic the style and tone of reputable media outlets and create convincing content that appeals to people’s emotions, biases, and expectations. AI-generated misinformation can also leverage social media platforms and networks to amplify its reach and influence by exploiting algorithms that favour sensationalism, novelty, and popularity over quality, accuracy, and relevance.

Another challenge in combating misinformation is that large language models (LLMs), the main technology behind AI-generated content, are biased and incomplete. LLMs are trained on massive amounts of text data collected from the internet, which reflect the biases and gaps present in society and culture. LLMs learn to reproduce and amplify these biases and gaps in their outputs, which can lead to harmful and misleading content. One type of bias that LLMs can perpetuate is second-order bias, which is the bias that arises from the way data is organized, categorized, and represented. Second-order bias can affect how LLMs understand and generate information, such as classifying entities, assigning attributes, inferring relationships, and constructing narratives. These can also affect how LLMs interact with users, such as how they respond to queries, provide feedback, and adapt to preferences.

Second-order bias can make misinformation more problematic at scale because it can affect not only the content but also the context and purpose of information. For example, it can influence how LLMs frame and filter information to suit different audiences and agendas, as well as manipulate and persuade users to accept or reject information based on their emotions, biases, and expectations. It can also influence how LLMs conceal or reveal their sources and intentions to users.

All of this is to say that the effort associated with generating false WhatsApp forwards like the example above (but far less benign!) for hundreds of thousands of people at a time is now rendered minuscule. Obviously, the public needs to develop critical thinking and media literacy skills to discern truth from falsehoods on a rapid-fire basis, but the consensus amongst researchers is that there is no silver bullet to this problem.

One can only hope that the human cost of developing AI-fuelled output that is difficult to distinguish from human creative output makes us pause and take stock of the situation. It may, however, be too late.

Matsyanyaaya: Cooperating to Communicate

— Bharath Reddy

The telecommunications network of a country qualifies as critical infrastructure. With the increasing adoption of 5G and the Internet of Things (IoT), almost everything we do will rely on this infrastructure. The recently signed India and US initiative on Critical and Emerging Technology (iCET) recognises next-generation telecommunications as one of the collaboration domains.

Within this domain, iCET identifies the following two areas for collaboration:

“Launching a public-private dialogue on telecommunications and regulations.”

“Advancing cooperation on research and development in 5G and 6G, facilitating deployment and adoption of Open RAN in India, and fostering global economies of scale within the sector.”

These welcome developments aim to address shared challenges for both India and US.

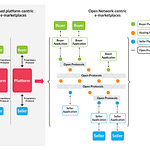

The telecom equipment industry has high entry barriers and is dominated by a handful of vendors. The top four vendors - Ericsson, Nokia, Huawei and ZTE - share around 85% of the Radio Access Network (RAN) market share. Sanctions and bans imposed against Huawei and ZTE further limit vendor choice. The lack of competition in the market could lead to a decline in innovation, an increase in prices and the risk of disrupted supply chains.

Several applications necessary for our daily life, such as communications, autonomous vehicles, and smart cities, require a secure and reliable telecommunication infrastructure. The choice of vendors is critical. It’s no wonder many states have implemented sanctions against Huawei, recognising it as a potential threat to national security. The telecommunications giant has close ties to the Chinese state. Given the geopolitical climate, relying on an adversary to maintain and upgradation of critical infrastructure is not an option.

The companies with the largest RAN market share are full-stack vendors that offer tightly integrated solutions. Open RAN promises to reduce entry barriers by disaggregating the RAN ecosystem. This allows smaller vendors to enter the market by building interoperable and modular components. However, this comes with the risk of complexities in system integration. The responsibility of a reliable and secure system will shift from a single vendor to system integrators and regulators. Given this market dynamic, system integrators and regulators need to develop the skills and capacity to integrate and validate the robustness of such systems.

Chinese companies dominate in 5G/6G standard development organisations such as the 3GPP. The disaggregation caused by adopting Open RAN should enable more innovation and broader participation in standards development. Open RAN adoption is progressing slowly, but it can play a more significant role in 6G. Cooperation between India and US in research and development in 5G, 6G and Open RAN will stand both countries in good stead. It will help build resilient supply chains and technical competence in these critical technologies.

Antariksh Matters: A vehicle worth reusing

— Pranav R Satyanath

On April 2nd, the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) conducted an autonomous landing test of the Reusable Launch Vehicle — a spacecraft that looks a lot like an uncrewed spaceplane. The test was indeed unique as the RLV was carried to an altitude of 4.5 km by a helicopter, after which the RLV made an autonomous landing using on-board computers and navigation receivers.

The existence of the vehicle is no secret. The RLV Test Demonstrator has been in development since 2012. In 2016, ISRO mounted the test vehicle on a sounding rocket and carried out the first hypersonic flight experiment. Since then, the RLV has undergone several experiments to test the flight and landing characteristics of the vehicle. Since the vehicle’s inception, ISRO has envisioned the RLV to be a test bed for a launch vehicle that could become fully operational by 2030. Of course, the RLV is more akin to the space shuttle than the reusable rockets used by SpaceX or Blue Origin. The space shuttle, for its part, was far more expensive than what the National Aeronautics and Space Administration first calculated.

So the question remains: will the RLV suffer the same fate? The answer? No. This is because the ISRO’s space plane design is likely to be far smaller and more nimble than the Space Shuttle (the latter was designed to carry both heavy cargo and astronauts). Concepts for space planes have existed since the 1960s, most prominent of which was the Boeing X-20 Dyna-SOAR, which never made it past early testing. The RLV could follow the X-20 style lineage, which inspired space planes like the European Space Agency’s HERMES spacecraft and the DreamChaser mini space shuttle by the private company, Sierra Space. India’s space shuttle, therefore, could eventually develop into a spacecraft that will be mounted on top of the LVM-III rocket and carry astronauts into space.

Those who watch space activities closely will also recognise that the RLV looks rather similar to the Boeing X-37B spaceplane, whose purpose of exitance seems to be shrouded in secrecy. Indeed, as I have written in a previous edition of Technopolitik, the X-37B is far less sinister than it appears. While the spacecraft is used for military purposes, its capabilities are limited to reconnaissance and small satellite deployment.

It would not come as a surprise if the RLV is repurposed for military utility. After all, ISRO’s tweets mention that the test was developed along wide the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) and the Indian Air Force. Having a spaceplane similar to the X-37B will give India’s military space operators the ability to perform rendezvous and proximity operations, including the capability to deploy micro satellite for inspections.

Our Reading Menu

[Book] Algorithmic Modernity: Mechanizing Thought and Action, 1500-2000, edited by Morgan G. Ames and Massimo Mazzotti.

[Article] Engines of power: Electricity, AI, and general-purpose, military transformations by Jeffrey Ding and Allan Dafoe.

[Op-ed] The TikTok Debate Should Start With Reciprocity; Everything Else Is Secondary by David Moschella.

Share this post