Matsyanyaaya: Insights from recent OEWG discussions on Information and Communications Technologies

— Anushka Saxena

The militarisation of cyberspace is a reality. And to enable states to discuss and adopt common rules for global governance of cyberspace, on 31 December 2020, the United Nations General Assembly adopted resolution 75/240 establishing an Open-ended Working Group (OEWG) on the security of and in the use of Information and Communications Technologies. The mandate for the Group extends from 2021 to 2025.

The Group recently concluded its informal, inter-sessional meetings on 26 May, and deliberations put forth by various states give us some insights into the kind of talking points we could look out for during the fifth Substantive Session of the Group, scheduled for July 2023.

To summarise, various stakeholders, ranging from governments and representatives of UN bodies to scholars from think tanks and technology corporations, submitted ideas about what the 2023 Annual Progress Report (APR) should entail. All of their ideas either build on or expand what has already been discussed in the previous substantive and informal sessions in 2023 or the 2022 APR. Some interesting ideas are as follows:

Iran submitted a Working Paper on establishing a provisional directory of 'Points of Contact' (PoCs) on ICT and cybersecurity.

● The first proposal to develop such a global directory was tabled in the UN Governmental Group of Experts Reports of 2013 (A/68/98). Now, every GGE and OEWG discussion notes progress on the directory.

● The aim of this directory shall be for states to appoint field experts in technical or diplomatic positions (or both), which would be a part of a global PoC network debating everything from responsible state behaviour in cyberspace and the applicability of international law to defining threats to ICT.

● As we know, the current Indian government has quite a knack for portals, and to formalise the creation of a PoCs global directory, India, too, has proposed the creation of a Global Cyber Security Cooperation Portal. The proposal, submitted by India's Permanent Representative in New York in July 2022, states that such a Portal shall be voluntarily updated by states and maintained by the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs.

The UNOCT/UNCCT and the UN Counter-Terrorism Committee Executive Directorate presented proposals for 'capacity building'. The proposal by the former was basically about glorifying the successes of its Global CounterTerrorism Programme on Cybersecurity and New Technologies. But the latter proposal, presented by the UNCTED, emphatically highlights the challenge of malicious online activity by rogue non-state actors and how existing counter-terrorism infrastructure can be leveraged to deal with it.

● The important recommendation is to develop comprehensive training programmes for law enforcement personnel and criminal justice practitioners working with digital evidence. The mention of the latter may be an important signal of more private sector participation in navigating the legalities of what constitutes 'terrorism' in cyberspace.

Submissions from the private sector mainly highlighted which governmental proposals are the most crucial for focus on in the next substantive session and how they can be expanded or narrowed down:

● Stimson Center's submission iterated that the two major emerging technologies states should agree on are common threats to ICT Security are ransomware and Artificial Intelligence.

● It should be noted that both El Salvador and Czechia had made statements during the last substantive session in March on the need for developing standards on 'responsible state behaviour' in new and emerging tech like AI and Quantum. But these efforts would be futile until states can first agree on what harmful use of AI/ Quantum is, given the dual nature of such technologies, and then move on to standard-setting.

● DCX Technologies presented anecdotes on how to avert a ransomware attack and engage with the attacker. Two suggestions stand out from their four-page intervention – one, that knowledge of critical infrastructure is essential to know how to protect it (such as by using enterprise security tools to detect malicious behaviour), and second, that any response to a large-scale ransomware attack such as the one DCX faced in 2020 requires a transparent, multi-stakeholder mitigation model.

If adopted and developed, these ideas could provide meaningful direction for the next set of discussions at the OEWG-ICT. However, if we look at some of the concerns governments presented during the fourth substantive session of the Group earlier in March, we can safely conclude that some of these ideas are a massive jump ahead of the tide. For example, India's primary concern during the session was as fundamental as something can be – for states to converge on their definitions and interpretations of international law! Similarly, Kenya's proposal entailed that states at least converge on how to define 'common threats in the cyberspace'.

This is, however, not to say that there exist no agreements whatsoever – states at the OEWG have now come to agree that the UN Charter is readily applicable to cybersecurity (especially provisions under Articles 2(1), 2(4), and 33). In doing so, they have cemented the idea that existing global governance institutions like the International Court of Justice can be utilised even to resolve cyber-incident disputes peacefully. This has not stopped countries like Russia and Syria from proposing a new legally-binding mechanism to govern state behaviour in ICT, citing the inability of existing mechanisms to do so.

Overall, some convergence exists on building capacity, creating a global knowledge base involving both state and non-state actors, and creating a due diligence mechanism for states to respond to malicious activities originating from their territory. The next Substantive Session would be vital to understand how states respond to these ideas and whether they can agree to resolve some of the fundamental challenges facing the OEWG's ambitious goals.

Cyberpolitik : A “broadly” unclear Light-Touch Regulation for India’s Online Gaming Industry.

— Satya Sahu

Online gaming is one of the fastest-growing segments of India’s digital economy, with millions of users playing various games on platforms ranging from smartphones, consoles and PCs. India’s gaming population is pegged to reach 700 million by 2025, with a significant portion of players spending real money on games. (current conversion rate is about 24% or 120 million players. It is a good bet that this trend will comfortably allow the Indian online gaming industry's ambitions of growing to USD 8.6 billion by 2027.

However, online gaming also comes with challenges and risks, because it can serve as a pathway to gambling using real money, addiction, an easy target for cybercrime, and exposure to illegal illicit content.

So of course, the Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY) notified amendments to the Information Technology (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Rules, 2021, related to online gaming in early April 2023. The amendments aim to enforce greater due diligence by online gaming intermediaries, such as platforms, websites, and apps that offer online games, and to protect users from illegal betting and wagering online. The amendments also envisage the creation of self-regulatory bodies (SROs) that will register and certify permissible online games and resolve complaints through a grievance redressal mechanism.

In most regards, the amendments have garnered applause from the gaming industry for being an unusual example of a light-touch regulation and promoting the idea of a trustworthy self-regulating market. It is a rare example of an enabling legislation meant to promote regulatory certainty without much in the way of prescriptive mandates. But with the lack of prescription, also comes uncertainty, particularly in the matter of definitions involved in deciding what constitutes "online gaming", "betting”, or "gambling. While jurisprudence across the country is settled on the distinction being whether the game in question has an element of skill or an element of chance (with the latter legally prohibited), the Rules do not provide any assistance in making that distinction clear.

There is also a significant issue about the implementation of these regulations due to the fact that gambling is a state list subject under the Indian constitution; however, the discussion on federalism in this context is beyond the scope of this post.

This post’s focus, however, is the definition of “user harm” in the context of online gaming. As per the explanation to Rule 3(1)(b)(ii), “user harm” and “harm” mean any effect which is detrimental to a user or child, as the case may be.

Even at a cursory glance, this definition is unusually broad and vague, leaving much room for interpretation and discretion by the government and the SROs. For instance, would considerations of obscenity, defamation, hate speech, discrimination, harassment, cyberbullying, cyberstalking, phishing, hacking, identity theft, addiction, or compulsive behaviour etc be relevant while defining “harm” in the context of online gaming?

How will these terms be defined and measured? Who decides whether an online game is likely to incite any of these harms? What are the criteria and standards for such decisions? How will the users be informed and educated about these harms and their consequences?

Moreover, a definition of user harm that does not take into account the diversity and complexity of online gaming genres, formats, modes, and audiences would be woefully limited. Online gaming is not a monolithic phenomenon, but a rapidly evolving one, with different types of games catering to different players.

In games, the depiction of drug use, violence, and sexually explicit content is handled by certification and age-rating systems like ESRB and PEGI in the US and the UK respectively, with generally consistent decision-making. In the case of India, the Rules mention the objective of tackling content-related concerns in terms of depiction of violent or inappropriate content. However, Rules 4A(8) and 4C have imposed an obligation on the SRO to ensure that the verification process to determine a game’s permissibility be based on a self-devised framework which assesses whether an online game contains adequate safeguards against user harm. The only considerations to be used while formulating said framework, are “self harm and psychological harm”, which do not do much to circumscribe our definitional woes.

The idea of the SROs to also act as a classification and age-rating body is a possible step in the right direction assuming that multiple SROs will not create conflicting frameworks for verification. While India’s approach may end up as a beefed-up version of the US and the UK (with legal liabilities on the online gaming intermediaries, and direct oversight of the Union Government etc.) , the case of Australia’s National Classification Code should serve as a warning of the kind of distortions that can be created in a regulatory regime when overbroad concepts are used to define what constitutes “harm” to the player. Australia’s Office of Film and Literature Classification, bound by their legislative regime, can reject certification for a game if its depiction of sex and drug use is potentially portrayed “positively”. Because age-ratings and classifications directly impact the commercial success of games (as well as movies, which is usually used as a counterpoint against controversial classification systems which do not keep up with the changing nature of multimedia consumption), the Indian gaming market can potentially find themselves reworking key aspects of their games just to be able to get them onto the market. It is a costly endeavour to say the least.

As all these teething questions abound, one only hopes that a consistent framework is proposed to guide interpretations regarding the ambit of "user harm" before dispute redressal and adjudication processes inevitably commence in the future.

Antariksh Matters : China’s in a Hurry to Get to the Moon

— Aditya Ramanathan

China has announced an official deadline of 2030 for landing humans on the lunar surface. On Monday, Lin Xiqiang, the deputy head of the China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) said the mission to put humans on the Moon was underway and would include a programme of research during short visits.

Lin’s announcement confirms a public comment in April by Wu Weiren, a scientist with China’s lunar exploration programme, who said putting humans on the Moon by 2030 was “not a problem”.

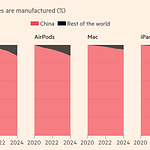

China has been steadily developing its crewed lunar programme. In 2022, it unveiled a model of a 90-metre-long moon rocket scheduled to undergo a flight test in 2027. Earlier in 2019, a promotional video showed off what appeared to be a crewed vehicle for deep space travel being developed by the China Academy of Space Technology (CAST).

China’s ongoing pursuit of sustained human presence in low Earth orbit will contribute to its ability to send people to the Moon. Lin’s official confirmation came at a press conference in which he also presented the new three-person crew for the Tiangong space station, which will launch into orbit this week, replacing three others who have been inhabiting the space station for six months. The experience with Tiangong will especially come in handy if China manages to proceed to the next stage of its lunar project: setting up a permanent base on the Moon.

Lunar Living

In 2021, China and Russia entered into an agreement to establish a permanent presence on the Moon. Eventually dubbed International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), the project was meant to be a direct counterpart to the United States’ Artemis programme, which, as of this writing, still intends to return humans to the Moon by 2025 and eventually set up a permanent presence on the lunar surface and in orbit.

In April, Wu publicly discussed a multi-stage plan for the ILRS up to 2050. This would include uncrewed missions and the setting up of a “basic version” that will be followed by a “full version” put together by 2040. Other stages include setting up a nuclear power source and research infrastructure. As with Artemis, China plans to support all this by putting a large constellation of satellites into lunar orbit for position navigation and timing (PNT), relay communications to the dark side of the Moon, and remote sensing.

Earthly Constraints

ILRS may have begun as a Russia-China collaboration, but since the outbreak of the war with Ukraine, Russia has been conspicuous by its absence from recent Chinese statements. Instead, China has focused on its own plans and has sought other foreign partners for its upcoming Chang’e uncrewed missions to the Moon.

China’s lunar ambitions are also evidently fuelled by its rivalry with the United States. However, China does not have the option of blending competition with a bit of cooperation. In 2011, the US introduced the so-called ‘Wolf Amendment’, which effectively bans US government funding to be used in cooperation with any Chinese entity without clearance from the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). While this is not technically an outright ban on space collaboration with China, its effect is much the same.

Indeed, it seems clear that NASA is determined to keep away from China. NASA’s administrator Bill Nelson has made alarmist remarks about China appropriating lunar territory, presumably to bolster support for the Artemis programme. However, if China and the US are engaged in a space race to the Moon, it is a relatively muted affair at the moment. Top politicians have not expended political capital on the issue, and space agencies have not seen an explosion in their budgets. The lunar ambitions of great powers will continue to be subject to Earthly constraints like economic downturns, wars, stubborn technological challenges, and myriad other pressing issues.

Our Reading Menu

[Podcast] - A Day in the Life of a Cop, a new limited series on 'policing' on All Things Policy, by Shrikrishna Upadhyay and Javeed Ahmed.

[Op-ed] Rs 2,000 Note Withdrawal: No demonetisation redux but RBI could have done it better, by Anupam Manur.

[Report] Defense Primer: U.S. Policy on Lethal Autonomous Weapon Systems, by Kelly M. Sayler.

Share this post