Matsinaya: Backdoors to state control

— Shailesh Chitnis

The Chinese government has signalled a shift in how it plans to control big tech. This month, news reports emerged that state-owned enterprises are set to take a 1% stake in two of its most prominent tech companies, Alibaba and Tencent.

Euphemistically dubbed "golden shares," this small stake grants special privileges and gives the government an outsized role in how these companies are run. Typically, these shares come with a board seat and the right to review or veto any content decisions. The stake in Alibaba was acquired by an investment fund set up by the Cyberspace Administration of China, the country's central internet regulator and censor.

So far, the arrangement seems to target companies with a significant user base for online content. Alibaba owns social media entities, including Youku, the Chinese version of YouTube, and the web browser UCWeb. Tencent operates Tencent Video, a popular Chinese streaming service. In April 2021, the government paid around 2M Rmb (~$290K) for a percent share in ByteDance Technology, the parent of TikTok.

Golden shares, known in China as "Special management shares" have been around since 2015 as a mechanism to control online content platforms. But over the past three years, the government has preferred more direct intervention to curtail what it perceives as an overreach by some of its largest companies. In October 2020, Alibaba controlled Ant Financial's IPO listing, which valued the company at a staggering $313 billion, which was pulled at the last minute. In July 2021, the ride-hailing app company Didi was banned from accepting new users over data privacy concerns. In the same month, China's edtech sector was crushed overnight when the government announced rules preventing these companies from making profits, raising capital, or going public.

With the Chinese economy faltering and Xi Jinping's coronation completed, Beijing appears to be taking a subtler path to control its biggest technology companies. Business leaders may see this as a preferable approach to more aggressive and, at times, unpredictable regulation. Having a government representative on the board will reduce the companies' independence. But there is less scope for sudden rule changes since the insider would be privy to all content moderation decisions. However, shareholders of these companies, in particular overseas investors, won't be too happy with this arrangement. They will have less visibility and control over how the business operates.

These concerns are now playing out publicly in how TikTok is trying to operate in the US. This month, the company shared details of a proposal that would spin off the US arm into a separate entity owned by ByteDance but entirely operated by US government-approved employees. It has also offered to allow Oracle and other third-party monitors to review its video recommendation algorithm. In the absence of a deal, the company is worried that it will be forced to sell its US operations or leave the market.

ByteDance's travails highlight how difficult it will be for Chinese-owned companies to straddle both the US and Chinese markets.

Antariksh Matters: Opening the doors for redressing orbital dangers

— Pranav R Satyanath

Over the past several issues of Techopolitik, we have covered several issues surrounding the weaponisation of space and the threats faced by satellites. One topic of particular interest has been the discussions and deliberations within the Open-Ended Working Group on Reducing Space Threats (OEWG).

We began covering the OEWG back in May 2022, when the group held its first meeting in Geneva. The second meeting of the OEWG was help in September. And in 2023, we approach the third meeting of the OEWG.

Much of the deliberations of the OEWG have been covered in a discussion document released in July 2022. During the deliberations, however, it became evident that India did little to be vocal about its own preferences for space risk reduction. After months of lamenting India’s lack of proactiveness, we at the Takshashila Institution have put down our set of recommended approaches for India to pursue at the Conference on Disarmament and the United Nations. The new discussion document titled, “Redressing Orbital Dangers: Approaches to Advance India’s Interests in Outer Space,” also provides an analysis of the US-led moratorium destructive DA-ASAT testing and India’s position on space risk reduction. Here’s an executive summary:

In December 2022, the United Nations overwhelmingly adopted a resolution that called for states to commit not to carry out destructive direct-ascent anti-satellite missile tests. The proposed destructive DA-ASAT missile test moratorium does not restrict the research, development and deployment of counterspace capabilities. India, however, abstained from voting on the resolution and indicated its preference for legally-binding instruments. Moreover, India has yet to put forward its proposals for members of international fora to pursue. This document recommends four approaches which India can pursue to secure its interests. These recommendations are:

Pursue legally-binding instruments which ban the destructive testing of anti-satellite capabilities in outer space.

Advocate for mutual proximity notifications wherein states notify one another during close approaches or when one satellite operator notices unusual satellite behaviour by another operator.

Promote sharing space situational awareness data to increase the knowledge of the space environment and build transparency and confidence between states.

Advance existing norms, rules and responsible behaviours in outer space by adopting and strengthening non-legally-binding measures.

No single recommended approach can redress all the threats in space. India must therefore advocate for multiple approaches in tandem to achieve peace and prosperity in outer space.

Cyberpolitik: Closing all backdoors through open-source

— Bharath Reddy

Open-source software (OSS) can help India achieve techno-strategic autonomy, economic growth, technology leadership, and skill development. As India takes on the G20 presidency, it needs to champion the adoption of OSS and create a sustainable ecosystem around it. A pledge by G20 countries to follow an OSS-first procurement policy that opts for proprietary closed-source solutions only when OSS options are unavailable can go a long way in creating an affordable and accessible common digital future.

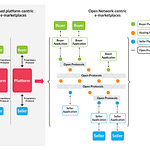

The rise of platforms and cloud-based services is a significant cause for concern in the information age. Big tech companies wield enormous power as gatekeepers of platforms. Network effects and vertically integrated services make it increasingly difficult for users to opt-out. User data often ends up being locked in silos. The need to have ownership and sovereignty over one’s data is increasingly being recognised as an essential consideration in determining our choice of software.

France and Germany have recognised the perils of having government communication on siloed big tech platforms such as Slack, Teams, WhatsApp or Telegram. They have taken the lead in moving government communication to a decentralised platform based on the Matrix open standard. France and Germany also have, to different extents, banned Microsoft’s Office 365 and Google Workspace, citing concerns around compliance with GDPR and data sovereignty.

These moves recognise that we live in an environment of increasing geopolitical risks. OSS offers a path to techno-strategic autonomy and data sovereignty. It provides unfettered access to secure, reliable and transparent technologies and ensures that data ownership stays with the users.

The ominous term surveillance capitalism accurately describes the practice followed by tech companies to exploit users' personal data for advertising-driven profit. Surveillance capitalism thrives on the power of platforms. Tech companies have convinced users to trade our privacy for convenience to such an extent that they can predict our behaviour and influence it. We need software and algorithms that are transparent and inspire trust. If we indeed want to mitigate surveillance, open-source is the way to go.

Building software using OSS components is now the de-facto model. Reusable modular OSS components can reduce costs and speed up the development process. A recent study shows that almost 97% of commercial software contains open-source code. This increased reliance on OSS puts additional strain on the communities of developers who maintain the code. Maintenance of OSS, including feature updates, bug fixes, and security updates, is a significant strain on the developers maintaining this code. Given that OSS forms the backbone of most software, a sustainable ecosystem with a contribution culture is essential.

Governments are some of the biggest purchasers of software and IT services. The union government already has a soft preference for OSS in software procurement. Current IT procurement policies, such as the e-Governance Policy Initiatives under Digital India of 2015, state that the government shall endeavour to adopt OSS in e-governance systems and that OSS should be mandatorily considered as one of the options. A stronger preference for OSS in government purchases can go a long way in creating a sustainable open-source ecosystem. IT procurement policies of the union and state governments should mandate that all software purchased through tax-payer funding be open-source. Proprietary and closed technologies should be considered only where adequate OSS technologies are not an option.

"Public Money? Public Code!" can be the guiding principle for government software purchases. In practice, this will lead to tax-payer-funded software having the freedom for everyone to use, modify, study, change and redistribute. The trickle-down effects will benefit society as a whole.

OSS is an integral part of our common digital future, and promoting it will lead to economic growth and skill development. It will promote open standards and interoperability. It will also lead to skill development, job creation and entrepreneurship. All of these benefits are aligned with the objectives of the G20 in promoting an affordable and accessible common digital future. Investing in OSS will also help countries of the global south access state-of-the-art technologies.

Adopting an OSS-first procurement policy by the G20 countries can create strong incentives for a vibrant open-source ecosystem. India must lead the way by adopting such a policy and champion other countries to pledge to do the same. In addition, G20 countries should also create a common fund which shall be used to fund critical OSS projects. The multiplier effects for the economy will far exceed the costs incurred towards maintaining these projects.

Our Reading Menu

[Blog] TikTok is a New Type of Superweapon by Gurwinder.

[Article] Trust but verify: Satellite reconnaissance, secrecy and arms control during the Cold War by Aaron Bateman.

[Report] Software Power: The Economic and Geopolitical Implications of Open Source Software by Alice Pannier

Share this post