Infopolitik: A Military Withdrawal in the Information Age

— Pranay Kotasthane

A month-and-half ago, I had tweeted this:

I had further written that:

“in the Industrial Age, such suppression could be covered up; that’s no longer the case in radically networked communities. The difference between the Afghanistan of 2001 and 2021 is mobile phones plus internet. Given these factors, the use of force against non-combatants is almost certain to receive instant condemnation from other countries. We can expect some backlash in US domestic politics as well. Such conflicts are global by default in the Information Age. The strength of these reactions might not be enough to change the overall decision (of the US). But it will be interesting to keep a watch from this angle.”

Little did I know that this assessment will play itself out within a matter of three weeks. Over the last ten days or so, the humanitarian crisis at the Kabul airport — more than the Taliban’s atrocities — has made it to phone screens across the globe. At the margin, this has had a positive effect of pushing national governments to allow more Afghan refugees in their countries. At the same time, the negative perception of the 2015 Syrian refugee influx has meant that the increase in refugee intake, at least in Europe, is unlikely to be significantly higher.

The Afghan situation is a subset of how a conflict will play out in the Information Age. Putnam’s classic two-level game framework describes the general case of conflict quite well. He argued that the politics of many international negotiations can be imagined as a two-level game.

At the national level, domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring the government to adopt favorable policies, and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among those groups. At the international level, national governments seek to maximize their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures, while minimizing the adverse consequences of foreign developments. Neither of the two games can be ignored by central decision-makers, so long as their countries remain interdependent, yet sovereign.

Here’s my illustration to describe this setup.

The politics of this setup operates as follows:

Each national political leader appears at both game boards. Across the international table sit his foreign counterparts, and at his elbows sit diplomats and other international advisors. Around the domestic table behind him sit party and parliamentary figures, spokespersons for domestic agencies, representatives of key interest groups, and the leader's own political advisors. The unusual complexity of this two-level game is that moves that are rational for a player at one board (such as raising energy prices, conceding territory, or limiting auto imports) may be impolitic for that same player at the other board. Nevertheless, there are powerful incentives for consistency between the two games. Players (and kibitzers) will tolerate some differences in rhetoric between the two games, but in the end either energy prices rise or they don't.

The key insight is this:

The political complexities for the players in this two-level game are staggering. Any key player at the international table who is dissatisfied with the outcome may upset the game board, and conversely, any leader who fails to satisfy his fellow players at the domestic table risks being evicted from his seat. On occasion, however, clever players will spot a move on one board that will trigger realignments on other boards, enabling them to achieve otherwise unattainable objectives.

In the Information Age, there’s a Level 3 game as well — the radically networked communities of the two negotiating parties can directly interact with each other. Given that groups can talk to each other directly, such interactions often affect what Level 1 and Level 2 negotiations can achieve. In the current refugee crisis, the level 3 connections are forcing a re-evaluation of hardened stances against migration at Level 2, at least in a few western countries.

As the situation at the Kabul airport improves, the focus will shift to the Level 3 interactions focusing on the Taliban’s repression. To what extent these interactions will affect the Level 1 & 2 games, I’m not sure. Nevertheless, this model provides a useful frame to parse the events that will unfold in Afghanistan in the coming months.

If the content in this newsletter interests you, consider taking up the Takshashila GCPP in Technology Policy. It is designed for technologists who want to explore public policy. By the end of this course, you will be able to use a #ResponsibleTech framework to systematically understand the ethical dimensions of technology advancements. Here’s a Twitter thread explaining the motivation behind the course.

Intake for the 30th cohort ends on 28th August. To know more, click here.

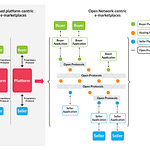

Cyberpolitik: The Taliban Question for Platforms

— Sapni GK

The Taliban's takeover of Kabul last week left many commentators and experts surprised. The quick capture of the elected Afghan government has caused great worry to social media platforms and their users in Afghanistan, wary about the digital footprints and the online lives of millions. When the Taliban was in power two decades ago, they had banned the internet in the country. However, today's landscape is different with an internet penetration of over 20% and four million social media users. In bigger cities like Kabul, people have been using the internet for the myriad conveniences it provides, including the use of social media platforms to voice opinions and concerns. For companies, content moderation, data handling practices, and a host of other digital rights are a cause of concern. For individual users under Taliban rule, these digital traces may be matters of life and death.

The uncertainty around the future government has left social media platforms in a fix. Currently, Facebook Inc. and YouTube ban Taliban content on their platforms. However, Twitter and LinkedIn continue to allow the use of their platforms, provided the content policies are not violated. Additionally, many of these platforms have limited the visibility of the networks of users in Afghanistan.

The Taliban has learnt the art of managing social media platforms. These platforms are an ideal tool in their arsenal to create noise and build narratives that drown dissident voices from within the country. They have also used technologies such as biometric identification to target members of the armed forces, which now stokes the fear of misuse of the World Bank-supported national digital identity card system, Tazkira.

Internet access opened up social and economic opportunities in Afghanistan, including the development of a nascent startup ecosystem in Kabul. These benefits now stand to be obliterated as the structure of most of these platforms is dependent on data collection. At the design level, they are structured to keep users continuously interacting and glued to the platform. The process of reclaiming the data held by these platforms, and removing one’s personal information is tedious, even in the presence of enabling legislation. This difficulty in erasing digital traces may aid the Taliban in identification and targeting. The organisation is reported to have used Facebook to identify targets in the past. At times like these, an easier exit out of the digital ecosystem of these platforms - a kill-switch - seems a legitimate ask.

These companies have a lot of important decisions to make. Currently, the account of the President of Afghanistan remains suspended and inactive on Twitter, with no clarity on what happens if and when the Taliban is recognized as a legitimate government. Bigger questions arise in the absence of the 2006 constitution and a new regime based on a rigid interpretation of Sha'aria Law. Law enforcement, which may or may not follow the international norms of liberal interpretation of rights, would be a challenge for these platforms. To operate legitimately in the state, they might have to hand over incriminating evidence for acts previously not designated as crimes, contributing to the violation of otherwise accepted human rights such as free speech. It is a slippery slope for platforms on counts of privacy, data protection, content moderation, and free speech. Much depends on the stance taken by the international community and ensuring that these companies are not pushed to take calls denting the fabric of international political order.

Antriksh Matters #1: GSLV, Do Not Go Gently into the Night

— Aditya Pareek

The cryogenic upper stage of a Geosynchronous Satellite Launch Vehicle (GSLV) failed barely five minutes into its ascent. According to media reports, the failed mission also took out an expensive and essential advanced Earth Observation Satellite, EOS-03/GISAT-1 along with it. ISRO expected the mission to be a success and even published detailed specs of the mission on its website.

The loss comes after the launch of EOS-3 was delayed for nearly a year and a half following the pandemic. It’s a blow to India’s Earth-imaging capabilities, at least in the short term.

According to this New Indian Express editorial:

GISAT-1 was planned to be the first of two such identical satellites to be put into space to relay back crucial data. The two satellites were planned to image in the multispectral and hyper-spectral bands to provide near real-time pictures of large areas of the country—selected field images every five minutes and entire Indian landmass images every 30 minutes at 42-metre spatial resolution.

As this piece in The Print by Sandhya Ramesh explains, when compared to the failure rate of missions undertaken by space programmes and agencies of other nations, ISRO still fares very well.

Although ISRO has attributed the failure to a technical anomaly, more details if they are ever revealed, will only come out after an investigation. It may be too early to judge if the latest failure of the GSLV platform will result in delays and further setbacks for big-ticket India space programme missions like Chandrayaan II or Gaganyaan.

Antriksh Matters #2: Artemis and India’s Moonshot

— Aditya Ramanathan

In late July, the government of the Isle of Man, a self-governing British Crown Dependency with a population of less than 100,000, announced that it had agreed in principle to join the Artemis Accords.

The Accords are a series of bilateral agreements between the United States and other countries. First announced in October 2020, the Accords lay down norms for lunar exploration. They are a prerequisite for joining NASA’s Artemis lunar exploration programme.

At present, 11 other states have signed the Accords with the US.

The Isle of Man sought to become a hub for the global commercial space industry. If it signs the Accords with the US, it will join the United Kingdom, Brazil, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, the UAE, Canada, Ukraine, Italy, and Luxembourg.

The Artemis Accords pose a dilemma for India: signing them and joining the Artemis programme will greatly aid India’s own lunar ambitions. However, the Accords also potentially open up the moon and other celestial bodies to unregulated mining, and de facto assertions of ownership of the celestial real estate.

Despite these risks, it makes sense for India to sign up to the Accords while maintaining its flexibility by pursuing other options, including space cooperation with Russia, and pushing for a new set of multilaterally accepted rules for space activity.

The Promise and Peril of Artemis

The Artemis Accords list 10 principles that seek to lay down norms for operating on the Moon.

These are: the use of space for peaceful purposes, transparency, interoperability, emergency assistance, registration of space objects, release of scientific data, protecting heritage in space, allowing the extraction and use of resources in space, deconflicting activities, and managing orbital debris and ensuring the safe disposal of spacecraft.

Most of these principles are innocuous and in line with the 1967 Outer Space Treaty (OST), to which all spacefaring states adhere. The provision for protecting heritage in space is primarily meant to protect areas of historical significance like the site of the 1969 Apollo 11 Lunar Module landing in the Sea of Tranquility.

The provision that raises the greatest concern is the one allowing the extraction and use of resources. While the OST bars states from asserting sovereignty on celestial bodies, it leaves open a loophole wide enough to allow two things: for states and private entities to claim ownership over resources extracted from celestial bodies, and for private entities to claim ownership or stewardship of celestial real estate (without an associated claim of state sovereignty). Indeed, the innocuous provision for deconfliction could allow states or private entities to declare ‘exclusion zones’ with no time limit, making possession nine-tenths of the law.

The Artemis Accords appear to be well designed to take advantage of this loophole.

It is not surprising that the US would seek such provisions. It dominates the commercial space industry and stands to accrue the greatest benefits. In 2015, the US Congress passed a bill that allowed private entities and citizens to use the resources of celestial bodies. Later, in April 2020, President Donald Trump signed an executive order instructing the Secretary of State to pursue diplomatic agreements that enable “commercial recovery and use of space resources”.

India’s Imperfect Options

Why should India care? Unregulated mining and claims of ownership, whether de facto or otherwise, could lead to negative externalities and deny smaller spacefarers opportunities.

The greatest potential negative externalities from mining would be the spread of lunar dust, which would be propagated quickly across the Moon’s low gravity, zero-atmosphere environment. This extremely fine dust can hamper and endanger lunar operations.

These externalities will become even more evident when the principles of the Accords are extended to the Asteroid Belt, where mining could create debris fields and even dangerously modify the orbits of smaller asteroids.

Finally, the finders-keepers model of lunar governance could allow larger spacefarers to monopolise the Moon’s resources, leaving smaller spacefarers like India at their mercy.

India has three options: one, it can sign the Artemis Accords (and thus join the Artemis programme), two, it can join rival programmes such as the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) programme led by Russia and China, and three, it can pursue multilateral agreements through the UN or other bodies.

As a medium-rung spacepower, India cannot fulfil its lunar ambitions on its own. It can only do so in cooperation with others. That means eschewing both the Artemis and ILRS programmes is not a viable option for India. While India must continue to pursue bilateral space cooperation with Russia, its prospects with the ILRS programme may be limited because of the presence of a hostile China. The Artemis programme, which includes the other three members of the Quad, as well as other friendly spacefarers, offers better prospects in the short term. India would benefit from signing up for it.

However, over the longer term, India must seek to maintain its flexibility and leverage by seeking to participate in all multilateral lunar exploration programmes, whether they be Artemis, ILRS, or other future projects. Simultaneously, India must also nudge spacefaring states towards multilateral norms regulating activities on celestial bodies, whether through UN-based mechanisms or independently. The best outcome for India isn’t to pick one option, it is to pursue all of them.

Check out Takshashila’s paper on India and the Artemis Accords here.

Antriksh Matters #3: Satellites for Climate Change Research

-Ruturaj Gowaikar

Two recent events highlighted the importance of satellite-based sensors in climate change research. The first being an announcement about BRICS Remote Sensing Satellite Constellation and data sharing. And the second being the publication of the 6th assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

BRICS agreement on Remote Sensing satellites

This agreement was signed at a meeting chaired by India on 17 August and saw the presence of the respective chiefs of the space agencies of BRICS states. The chairman of ISRO and Secretary in the Department of Space, K. Sivan, was the signatory on behalf of India.

This agreement paves a way to form a virtual constellation of six satellites already in orbit, and their respective ground stations at Cuiaba of Brazil, Moscow Region of Russia, Shadnagar–Hyderabad of India, Sanya of China, and Hartebeesthoek of South Africa. The satellites are CBERS-4 (jointly by Brazil and China), Kanopus-V type (of Russia), Resourcesat-2 and -2A (of India) and GF-6 and ZY-3/02 (of China).

The CBERS-4 is a second-generation satellite of the China-Brazil Earth Resources Satellite Series. It is equipped with a MUXCam (Multispectral Camera), PanMUX (Panchromatic and Multispectral Camera), IRS (Infrared System) or IRMSS-2 (Infrared Multispectral Scanner-2), and WFI (Wide-Field Imager). All these sensors make it ideal to carry out its mission objectives of monitoring forest and water resources.

The Russian Kanopus-V is a minisatellite launched with an aim to monitor the Earth's surface, the atmosphere, ionosphere, and magnetosphere and study the probability of strong earthquake occurrence. Sensors on it are PSS (Panchromatic Imaging System), MSS (Multispectral Imaging System), MSU-200 (Multispectral Scanner Unit). These sensors enable it to monitor land surfaces, sea surfaces, and ice sheets as well.

Indian satellites Resourcesat-2 and -2A have a mission objective to provide remote sensing data for integrated land and water resources management at the micro-level. On-board sensors allow them to acquire images in four spectral bands ranging from Visible and Near-Infrared (VNIR) to Shortwave Infrared (SWIR) wavelengths. These sensors are Advanced Wide-Field Sensor (AWiFS), Linear Imaging Self-Scanning Sensor-3 (LISS-3), and Linear Imaging Self-Scanning Sensor-4 (LISS-4).

The Chinese GF-6 (Gaofen-6) is an optical satellite developed under China’s High-definition Earth Observation System (CHEOS). It is the first precision agriculture observation satellite of China, with capabilities of ultra-wide imaging. It can capture images in the NIR spectra. The second Chinese satellite is of the ZiYuan series. The ZY-03 is a civilian satellite with high resolution and stereoscopic mapping capabilities. Stereoscopic imaging is possible due to the offset of 22º between its three in-line telescoping cameras. ZY-03 can also capture images in NIR.

Reports indicate that the idea for a BRICS constellation had its origin in a 2016 meeting under the auspices of the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs. The successful signing of this agreement between India and China is an important milestone for the two countries with little history of formal cooperation in the space sector.

IPCC report of 2021

The 1st part of the 6th IPCC report has data and analysis on recent improvements in the field of climate science. This includes data on heatwaves, the effect of clouds on climate systems, and data on extreme events like droughts and precipitation at a local level. Such studies were possible as climate models have become accurate due to the incorporation of data obtained from satellite-based sensors. The contribution of data from satellite sensors in IPCC reports is steadily increasing after the 4th report in 2007.

Satellite-based sensors have advantages over land-based sensors to monitor essential climate variables (ECVs). They can provide high-quality, continuous data of a region, and the instruments aren’t affected by local weather conditions. Moreover, certain ECVs like gravitational effects of continental ice sheets can only be monitored by satellite-based sensors. The Global Climate Observing System (GCOS) currently specifies 54 ECVs, of which about 60 per cent can be addressed by satellite data.

Another factor in the improvement of climate models is the standardization of data processing, sharing, and reporting parameters between space agencies, governments, and scientists of various countries. Organisations and agreements like the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) of the World Research Climate Programme and the Office for Outer Space Affairs of the United Nations promote cooperation in this area. Thus, satellites will continue to provide an ideal platform for climate monitoring and international cooperation.

Our Reading Menu

1) [Paper] The use of remote sensing to support the application of multilateral

environmental agreements by Nicolas Peter

2) [Paper] Reimagining Social Media Governance: Harm, Accountability, and Repair by Sarita Schoenebeck and Lindsay Blackwell

3) [Paper] Escaping the 'Impossibility of Fairness': From Formal to Substantive Algorithmic Fairness by Ben Green

4) [Infographics and Article] How satellites are used to monitor climate change

Share this post