Antariksh Matters: Shattering Space Record Myths

— Pranav R Satyanath

Earlier this week, a record was broken in the shadowy world of military space tech. At least, that’s what some of the headlines make you believe. The secretive X-37B Orbital Test Vehicle (OTV) uncrewed spaceplane, operated by the US Space Force, landed at the NASA Kennedy Space Center on November 12th after spending 908 days in orbit. It broke the previous orbital record (780 days) by a large margin. The spaceplane, which is built by Boeing, has been in operation since 2010. Its mission and purpose are largely unknown, building some sort of a myth around this mini-Space Shuttle-looking vehicle.

Let’s take a step back. From all the open-source images available, we know that the X-37B has a single liquid-fuelled engine built by Aerojet and powered by storable propellants. This means it can stay in orbit by increasing its altitude. So, one can say that spaceplanes are not very different from regular satellites, which operate for years and decades in orbit. Now compare those years and decades to 908 days. Not much, right? Well, yes. So long as the spaceplane can maintain orbital speed, it can stay in orbit as long as its operators wish.

Although we don’t know much about the X-37B’s true purpose, we know some meta details that give clues as to what the purpose might be. The programme that gave birth to the X-37B isn’t a secret. Back in the early 1990s, people in the US government got pretty worried about the costs of operating the Space Shuttle. It was reusable for sure, but it was a slow and painstaking process to get the vehicle back to space. So, the US Congress told NASA to go and look at other alternatives. The result was the Access to Space study, which outlined faster, better, cheaper and smaller alternatives to the Suttle. After pondering their heads over what to test, NASA began to fund a handful of companies to research and develop reusable spaceplanes, including Single-Stage To Orbit (SSTO) tech, which is considered the pinnacle of rocketry.

Chief among these experimental spaceplanes included Lockheed Martin’s X-33 and Orbital Science’s X-34 reusable launch vehicles, along with Boeing’s X-37 experimental space manoeuvring vehicle. By 1999, NASA saw the funds dry up and no progress to show. The US Air Force (USAF) was ready to take up the X-34 and the X-37 programmes. The X-34 programme got cancelled, and the X-37 was transferred to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Two years later, the X-37B was in the hands of the USAF.

From what we know, we can draw out two hypotheses:

The X-37B is a highly manoeuvrable vehicle used to inspect suspicious activities and objects in space.

The X-37B is a test vehicle for the US Space Force (and Air Force) which allows them to test hypersonic re-entry, autonomous capabilities and perhaps, deployment of small payloads.

A part of the second hypothesis is already confirmed. Astronomer and space watcher Jonathan McDowell reported that the X-37B launched a subsatellite named the FalconSAT-t8, an experimental payload developed by the Air Force Academy. The second hypothesis is less likely to be true, as small satellites can perform a far better (and less suspicious) job of inspecting suspicious activities and objects.

Like the US, the Chinese also have a handful of spaceplane projects. It will not be surprising that these vehicles will have both civilian and military uses. India is also testing a version of its spaceplane called the Reusable Launch Vehicle-Technology Demonstrator (RLV-TD).

Spaceplanes are interesting. But we must not get carried away by spooky headlines.

Comments on the Draft Telecommunications Bill, 2022

— Satya Sahu and Gayathri Poti

The draft Telecommunications Bill, 2022 will do more to prohibit Digital India's growth story rather than facilitate it. We outline some of its most glaring issues:

Definitional Over-breadth, Legislative Conflict and Procedural Lacunae

Explanatory Note to the Bill in para.51 reassures that provisions concerning internet shutdowns recognize citizens' rights; there is no enumeration of this safeguard in the concerned clause nor mechanisms for judicial oversight or review panels to record the legality of suspension orders à la the Telecom Suspension Rules, 2017.

The Union Government recently withdrew the Personal Data Protection Bill, 2021. In the absence of a data protection regime and an independent Data Protection Authority vested with powers to implement safeguards on the access and use of personal data by public authorities in line with the principles laid out in Puttaswamy and Shreya Singhal. , Clause 24(2)(b) contributes to the increasingly fragmented data protection framework in India, alongside the IT Act, 2000, SEBI Data Sharing Policy, 2019, Payments and Settlements Act, 2008 etc. Regulatory uncertainty and compliance costs within this framework become increasingly difficult due to the wide gamut of entities subject to the definition of "Telecommunication services" under Clause 2(2). The increased cost of compliance with implementing KYC norms and mandatory licensing regimes will result in extremely high barriers to entry for players in the OTT market. It will ensure that only market players with significant resources to meet these obligations can afford to remain in it, amplifying concerns about stifled innovation and competition in this oligopolistic sector.

Subjecting OTT platforms to DoT jurisdiction creates regulatory overlap with MeitY's powers, creating potentially conflicting laws, duplication of efforts by regulators and market players alike, ownership of implementation measures, and increasing costs of conducting business.

OTT platforms like real-time messaging services deploy E2E encryption. Currently, access to encrypted communication is governed by the 2021 Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code released by MeitY. Under this, significant social media intermediaries are only expected to enable the identification of the first originator of the information. The rules deliberately refrain from mandating access to the contents of the communication (especially since the 2015 draft rules that insisted on making available the plaintext of communications was met with heavy criticism), but Clause 24 empowers the Government to gain access to the contents of the communication as well. This conflicts with the 2021 Code and further aggravates the issue of regulatory overlap. The provision implicitly requires OTT platforms to create encryption backdoors and inevitably undermines Constitutional protection for free speech afforded by encryption.

The territorial applicability of the provisions of the Bill has not been described unlike in the Telegraph Act, 1885, and the IT Act, 2000, which circumscribe their application in terms of geography and cyber attribution. The telecom and OTT sectors depend on cross-border interconnectivity and rely on internationally administered infrastructure like satellites, marine fibre-optic cable networks, etc. It is necessary to foresee and describe the territorial limits of domestic law to avoid international conflict of laws to maintain market confidence and decrease legal costs and instances of interruption in critical services.

Clause 46 (k) of the Bill dilutes TRAI's standing to requisition information from the Government and provide recommendations before awarding licenses. Deleting the non-obstante clause and provisos to S.11 (1) of the TRAI Act eliminates TRAI's role in ensuring a level playing field for TSPs and fair and non-discriminatory treatment by the Government. Vesting TRAI with the power to investigate predatory pricing exacerbates existing overlap between the mandates of TRAI and CCI, increasing possibility of regulatory arbitrage.

Clause 24(1) vests the Central Government with the power to take temporary possession of telecommunication services, networks, and infrastructure, in the occurrence of any public emergency or in the interest of public safety. Clause 24(4) makes the exercise of this power concomitant with the duration of a public emergency or occasion. The Bill, however, does not provide any procedure for Government action nor define the terms' public safety' and 'public emergency', undermining the temporary nature of this power, inviting constitutional scrutiny and low investor confidence.

Insufficient Justifications for Overarching Policy

OTT platforms should be permitted to continue operating under the existing framework without any regulatory intervention until the ITU and similar foreign jurisdictions conclusively determine the regulation of such platforms. TRAI's 2020 recommendations propose no deviation from this approach, especially since there has been limited global progress concerning OTT regulation.

Compliance with KYC norms is mandated for the issuance of SIM Cards and broadband connections; extending this requirement for accessing OTT communication services is unwarranted. The rigours associated with KYC rules are reserved for tightly regulated sectors like banking, where identity verification systems combat the incidence of high-risk pernicious activities. Mandating adherence to the KYC process for creating an account on an IM/e-mail/video telephony platform is not only disproportionate but is likely to dissuade users from accessing critical services. In particular, KYC formalities will deter consumers from testing newer platforms which could result in market stagnation.

Clause 32 envisages framing regulatory sandboxes to enable innovation and technological development in the sector. However, it allows access to regulatory sandboxes only as part of the terms and conditions under its new licensing regime defeating the intent of a regulatory sandbox. Providing access to this environment only upon the award of a license raises the costs of introducing new technology in a fixed-capital-intensive sector like telecom and entrenches the market power of already dominant entities who can bear this cost. The extent and nature of the usage of new technology cannot always be preempted in the terms of a license at the time of licensing. This creates the future burden of bearing opportunity costs of not being able to leverage its own technology in new ways on the licensee, leading to avoidable legal costs and ad hoc renegotiation.

The authors are students of Takshashila’s GCPP (Technology & Policy) Programme.

Matsyanyaaya: Splinternet Conviction?

— Bharath Reddy

We often hear predictions about a splinter-net or a bifurcated Internet. What does this mean? And what are the incentives at play other than the obvious state control and censorship?

To get an idea of how the Internet could split and what it means, a good example would be Runet - the Russian national segment of the Internet. Russian interventions to create an independent national Internet range from state censorship to mandating ISPs to use national Domain Name System (DNS) servers (where website names are translated to addresses).

There are also forces from outside Russia incentivising the split as well. During the initial phase of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, there were appeals by Ukraine to remove Russian domains from DNS servers which would cut them off from the rest of the Internet. This request was rejected as it could destroy trust in a global internet if the DNS does not remain neutral. However, requests by Ukraine to certificate authorities that issue SSL and TLS certificates for websites have been more successful, creating barriers in the process. Lastly, the hardware sanctions and market exits following the conflict could potentially lead to a split in internet standards.

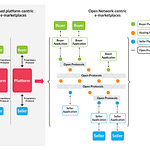

As you might know, the Internet is based on communication protocols which enable different devices to speak a common language and communicate with each other. Broadly, these protocols can be classified under - content, logic and infrastructure layers. While censorship at the content layer is quite common, a fork in the lower logic and infrastructure layers could have serious ramifications.

Network effects, protocol politics and geopolitics, come together here. The largest networks have incentives to refuse to be interoperable with competitors. In the current nature of the Internet, the US and its allies wield power to cut off competitors from critical chokepoints. This power has been exercised to an extent during the recent sanctions against China and Russia.

The threat of such actions creates incentives for bifurcated supply chains and in this world of bifurcated supply chains there would be takers for China’s vision of national internet sovereignty. In such a scenario, future network protocols such as New IP being developed by Huawei could become more widespread. The intelligence built into the protocols at the logic and infrastructure layers could enable more surveillance and control by the ISPs and the State.

The concerns around the splitting of the Internet is thus a complex interplay between technology, geopolitics, and the relation between the State and the individual.

The report titled “One, Two, or Two Hundred Internets” by the Center for Security Studies (CSS), ETH Zürich is an exciting read that covers this subject in detail. As the author hopes, it helps enable informed discussion and decision-making on splitting the Internet.

Our Reading Menu

[Opinion] Road Ahead for UPI: Free Public Infrastructure or Yet Another Payment Mechanism? by Rohan Pai and Mihir Mahajan.

[Chapter] Gene Editing and the Need to Reevaluate Bioweapons by Shambhavi Naik.

[Book] Cellular: An Economic and Business History of the International Mobile-Phone Industry by Daniel D. Garcia-Swartz and Martin Campbell-Kelly.