A happy new year to all our readers! To kickstart this year’s edition of Technopolitik, we have assembled a list of predictions for 2023 across tech sectors, ranging from online regulation, biotech and outer space. Maybe we can take stock of these predictions and see how much of it we got wrong (or right) at the end of this year!

Beginning from this edition, we also introduce a new section to our newsletter called Biopolitik, while will cover all the fascinating tidbits about the biotechnology industry and its intersection with policy and politics.

Be sure to check out our Reading Menu. This edition lists some of the best books that the authors have read from last year. With that, we wish you a great year ahead!

Cyberpolitik #1: Regulatory tech battles in India

— Shailesh Chitnis

Big tech is vulnerable. For the first time in big-tech history, technology platforms are confronting slowing growth and bottom-line pressures. Aggressive expansion during the pandemic years has given way to cost-cutting during a cooling economy.

Amazon recently announced plans to cut 18,000 workers, mostly in the retail, recruiting and devices businesses. Meta, the parent of Facebook and Instagram, has cut more than 11,000 workers, or about 13% of its staff. It's a similar story across other platforms — Salesforce, Snap, Twitter — no one seems immune.

Against this backdrop, regulators are getting more active in reigning in what they see as an overreach by these platforms. In the past, Indian regulators had given technology platforms a free hand. But increasingly, the Indian government has signalled its intention to shape the country's technology landscape.

In a series of rulings in October, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) fined Google almost Rs. 2,300 crores for abusing dominance with its Android operating system and the Play Store. The government is also getting into specifics of technology implementation with new rules around standardising chargers (USB-C) and upholding consumers' right-to-repair for devices.

In 2023, expect more activity. The gatekeeping role of Apple and Google, which they exercise through their app stores, will be challenged. But since commissions from these stores are a significant revenue source for both these companies, any moves to change this structure will be a long legal battle. With the government's active role in market design, expect more public battles between incumbent tech and the government. Adding to the tech vs regulators battle, India will also be gearing up for general elections in 2024. As the elections draw closer, we can expect the conversations and controversies on the role of social media platforms in disseminating information to be pitched even further.

Indeed, 2022 was a busy year for technology policy-making with the semiconductor manufacturing policy and a revised draft of the much-awaited digital data protection bill. But this year, the government has promised to introduce a complete overhaul of the IT Act, which governs much of the digital ecosystem. The IT Act was passed in 2000 and needs to be set up for all the complexity of the internet today - from intermediaries and platforms to AI and data privacy. We also expect the bill's first draft to cover a wide range of online platforms, including social media sites, e-commerce entities and ad-tech platforms.

This act can have far-reaching consequences for businesses and civil society since all problems are now technology problems in some form.

Biopolitik: Pandemics and regulatory politics

— Saurabh Todi

The World Health Organisation (WHO) in 2023 is expected to accelerate negotiations on a draft international pandemic treaty governing prevention, preparedness, and response to future pandemics. The World Health Assembly (WHA) in December 2021 launched the process of negotiating a historical global accord. It established an International Negotiating Body (INB) to formulate a 'WHO convention, agreement or another international instrument' to aid a united global response to any infectious disease crises in the future.

Countries felt the need for a new treaty due to various challenges made conspicuous by the experience of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. These include equitable distribution of vaccines and health services among and within countries, knowledge and data sharing, and strengthening countries' capabilities to respond to health emergencies. Although there has been a broad consensus on the ways of working and broad policies that will guide this process, there are also significant disagreements between member states.

A central sticking point is the legal nature of this treaty. While the majority of the WHO member states favour a legally-binding instrument, there are differences in how to approach this issue. For example, the WHA has agreed to adopt the global instrument under Article 19 of the WHO constitution, which enables the assembly to draw up binding agreements on a wide range of issues under its mandate. But some countries want the treaty to fall under Article 21, which limits the number of topics that can have binding agreements. Furthermore, some prefer "non-legally binding recommendations" in the draft.

In December 2022, at the third meeting of the Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB), a Conceptual Zero Draft (CZD) of the instrument was released, which has been developed by the Bureau of the INB following widespread consultation. During the meeting, the task fell on INB to develop a "zero draft" in order to start negotiations at the fourth INB meeting scheduled for February 2023. The WHO has committed itself to a timeline where INB will deliver a progress report to the 76th World Health Assembly in 2023 and; submit an outcome document for consideration by the 77th World Health Assembly in 2024.

Interestingly, India has maintained a studied silence over its position on this proposed treaty. As an advocate of the interests of the global south, it must ensure the security of the interests of the developing countries during these negotiations. Given the difference of opinion among countries on these issues, it would be interesting to see how the global community reaches a consensus on this crucial initiative.

Antariksh Matters: A Space Policy at Last?

— Aditya Ramanathan

Against my better judgement, I am going to make predictions that may be largely wrong. First, the easy part: sometime in 2023, the Indian government will release a Space Policy. While the release of this policy has been long-promised, it is more likely than not to be finally made public this year.

Now, the more difficult part: predicting some of the broad contours of the policy. I’ll start with some brief background. In 2017, the government released a draft Space Activities Bill for comments. The bill was an important step in laying down a legal framework under which space companies can operate. However, the feedback wasn’t good. The bill had vague definitions and granted excessive discretionary authority to government officials. As an example of vagueness, the bill only covered Indians or private entities registered in India, leaving foreign collaborators in a regulatory dead zone.

Similarly, it defined ‘space activity’ so broadly that even a start-up doing preliminary research and development might find itself coping with a barrage of licensing requirements. The draft bill also offers little clarity on liability. India is a signatory to the 1972 Liability Convention, which makes states liable for damage caused by space activities. The bill simply states that the government will decide the amount of money for which a private entity is liable - the sort of provision that is virtually guaranteed to scare off investors.

A lot has changed since 2017. The government has pledged to revise the 2017 draft bill based on comments received. It has also created the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe) to act as a nodal agency for private space companies. The next steps are to release a Space Policy followed by the heavily modified Space Activities Bill. So here are my three predictions for the Space Policy:

One, the policy will be genuinely oriented towards encouraging private sector space activity and will identify it as a key priority for India. There’s enough evidence that the government takes this seriously. The private space economy is (rightly or wrongly) seen as an important component of the “Atmanirbhar Bharat” vision of a self-reliant India. The space economy is also seen as a key catalyst for high-technology industries. The Indian Prime Minister’s push for the creation of the industry body Indian Space Association (ISpA) is indication enough that this support extends to the apex of the political leadership.

Two, despite this commitment to private industry, the verbiage of the space policy will still place the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) at the centre of India’s space aspirations. Indeed, it is quite likely that the policy will consider the primary role of India’s private sector to be a supporting ecosystem for ISRO rather than a dynamic entity in its own right. This is a somewhat shakier prediction to make, and it is, more than anything else, a hunch based on statements made by ISRO officials and an awareness of the influence ISRO and the Department of Space wield.

Three, the policy will likely offer a potential solution to the issue of liability. I suspect the proposal it will come up with is the creation of a space liability fund that can act as a sort of insurance pool. Typically, such funds will be built by space companies pledging a portion of their profits, but the details would probably only become clear in the Space Activities Bill.

So that’s my largely optimistic prediction for 2023. Whatever the actual outcomes, we’ll dissect them in detail for you in this newsletter.

Cyberpolitik #2: In Service of the Digital Public Infrastructure

— Bharath Reddy

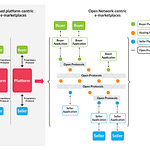

As we enter 2023, we will see increased deployment of different facets of digital public infrastructure (DPI). As we have seen with UPI, this can lead to financial inclusion and empowerment of citizens, but it comes at the cost of centralising platforms in the hands of the government.

Different facets of DPI, such as the Account Aggregator framework, Open Credit Enablement Network, UHI for health, and enhancements to Aadhaar and Digilocker, are expected to be deployed and adopted widely. These improvements will likely lead to the seamless delivery of services and unlock easy access to citizens' data across different silos.

In addition to this, as Rahul Matthan writes, DPI will also serve as a techno-legal framework for data governance. Across the world, governing how data is collected and used has proved to be a challenge. Regulations have yet to be successful. Companies have been able to circumvent the law, and the capacity required for enforcement is also relatively high. Moreover, since DPI can be encoded into the public infrastructure, they might offer a better solution for compliance. Requests for data, consent and provision of minimal purpose-specific data can be built into the infrastructure, making compliance easier to enforce.

However, these advantages come at the cost of concentrating power over the platforms in the hands of the state. The state has access to large amounts of citizens' personal data and is responsible for safeguarding it. It also has regulatory control and gatekeeping privileges for these critical platforms.

Concerns over regulatory access are critical given that we expect the Digital Personal Data Protection Bill (DPDPB) and Telecom Bill to be tabled in Parliament this year. The broad exemptions granted to government entities and the lack of independence of the proposed Data Protection Board in the draft DPDPB, 2022, are a cause for concern. The draft Telecom Bill 2022 has expansive definitions and allows for greater state surveillance.

Since both bills have received comments already, we can expect them to be passed this year. The checks and balances they will enforce will play a crucial role.

Our Reading Menu

[Book] Chip War: The Fight for the World's Most Critical Technology by Chris Miller.

[Book] 10% Human: How Your Body’s Microbes Hold the Key to Health and Happiness by Allana Collen.

[Book] Human-Build World: How to Think about Technology and Culture by Thomas P. Hughes.

[Book] The End of Ownership: Personal Property in the Digital Economy by Aaron Perzanowski and Jason Schultz.

Share this post