Matsyanyaaya #1: Opening up to open-tech

— Bharath Reddy

"Open Tech" refers to transparent, inclusive technology and embodies the freedom to use, study, modify and redistribute to the maximum extent possible. The definitions of open-source software, open standards, and open-source hardware are well understood. "Open Tech" is an umbrella term that includes all of these technology areas.

The usual arguments promoting open source technologies highlight reducing costs, avoiding vendor and technology lock-in, and the ability to customise. But, given the current geopolitical climate, access to state-of-the-art technology cannot be taken for granted. Supply chain resilience and tech sanctions are a cause for serious concern.

The acquisition of advanced technologies is not an end in itself, but a means to bring peace and prosperity to all Indian citizens. Unhindered access to state-of-the-art technology and foundational knowledge is, therefore, in India's national interest. External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar echoed this sentiment when he said India "cannot be agnostic about technology" as there is "a strong political connotation in-built into technology".

Open tech can help India achieve techno-strategic autonomy, economic growth, technology leadership, and skill development. The "openness" also helps foster trust, broaden access to technology and further democratic values.

Open tech, by its nature, is both non-rival (its use by someone does not diminish the utility to others) and non-excludable (its access cannot be denied to anyone). In economic terms, this qualifies it as a public good. As we see with other public goods, such as clean air or street lights, the incentives are weak for markets or individuals to tend to the maintenance and upkeep of public goods. This is visible in one of the main problems facing open-source software today.

A recent study shows that almost 97% of all commercial software uses open-source code. A large number of open-source projects are maintained by individuals or small communities of developers without adequate funding. This growing reliance on open-source software increases the burden on maintainers of this code to keep the software secure, bug-free and up-to-date.

Other areas, such as the open-source hardware, are in a nascent stage, and India could gain a valuable head-start given a favourable policy environment. This is especially important given the silicon geopolitics playing out between the US and China.

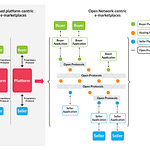

Open standards have a range of benefits, such as removing entry barriers, promoting interoperability, and lowering costs. The government needs to encourage the promotion of open standards and also represent India-specific requirements at various international Standard Development Organisations.

The existing policy landscape includes a preference for open-source software in procurement and a policy on standards for e-governance at the Union and State governments. However, given the growing importance of open tech, a comprehensive open tech strategy is indispensable.

This short essay is a preview of an upcoming Takshashila Report on an open tech strategy for India.

Apply here: https://bit.ly/pgp-jan23-nl

Antariksh Matters: Buying space power?

— Pranav R Satyanath

Earlier this week, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) launched its first rover, Rashid, towards the Moon’s surface. The rover was carried on a Falcon-9 rocket along with a miniature rover from the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA). But there’s a catch. The UAE did not build the Rashid rover, but it was built under contract by a Japanese private space venture called ispace. When we think of space-faring nations of the world, the UAE does not immediately strike a chord.

However, the desert country has big space ambitions for the next decade. It has signed the US-led Artemis Accords. It has also signed an agreement with China to collaborate on future Moon missions. This is a surprising move since China has opposed the Artemis Accords and challenged its legality in the broader context of international space law. The country also boasts a full-fledged Mars programme. In March 2021, UAE became the first Arab country to place a probe in Mars orbit as part of the Emirates Mars Mission. The probe, named Hope or Al Amal in Arabic, was built by the Mohammed Bin Rashid Space Centre in collaboration with the University of Colorado, Boulder. Furthermore, the UAE also boasts an astronaut programme in partnership with NASA’s Johnson Space Center.

But UAE is not the only Arab country to veer into the lucrative and prestigious space sector. Saudi Arabia plans to invest $2.1 billion into its space programme as part of its larger Vision 2030 mission. The country set up the Saudi Space Commission in 2018 and placed the SGS-1, a communications satellite built by Lockheed Martin, in February 2019. Earlier this year, the Saudi Space Commission and Axiom Space, a US-based private space company, also signed a deal to send the Kingdom’s astronauts into space.

Petro-states by the likes of UAE and Saudi Arabia are the newest entries into the small and often restrictive space club. Their rise is only possible due to the large-scale commercialisation of space activities. Using their large reserves of income, petro-states can buy commercial services with relative ease and break into the space club rather than spend years building a domestic space industry from scratch.

This phenomenon raises the question: what makes a country a space power? More often than not, those counties can launch rockets (or missiles), and perhaps, the ones that can build satellites are deemed as space powers. For much of the Cold War, orbital rocketry (and missile technology) captured the imagination of a space-faring nation, one that could build bigger and more powerful rockets to send payloads to the Moon and beyond. Although some of these rockets and satellites were built by private entities, their operations, for the most part, were controlled by national space agencies.

Of course, not all space powers are born equal. Space powers can be ranked based on the range of activities they carry out across their civilian and military space programmes. The United States and Russia by far carry out the most space activities, with China slowly playing catch-up. France, India and Japan could fall in the category of middle space powers due to similarities in their space capabilities.

Countries like Saudi Arabia, UAE and Turkey could be categorised under an entirely new category of space powers. Their power is drawn from their ability to redirect financial resources to attract commercial collaborators. As I point out in my discussion document on the future of India’s space station programme, commercial collaboration is a new mechanism through which countries with limited capabilities can partner with private entities to augment their overall capabilities without the need for large-scale investment.

As more private entities enter the space sector, we will likely witness more commercial collaborations in the future. Thus, making space easily accessible to many more countries.

Matsyanyaaya #2: Vibing with nuclear fusion

— Saurabh Todi

The Financial Times reported that the scientists at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL) in California had achieved a net energy gain in a nuclear fusion reaction for the first time, which promises to become a cheap and carbon-neutral source of energy. The US Department of Energy (DOE) is expected to officially announce the breakthrough on Tuesday. This significant feat was achieved by LLNL’s National Ignition Facility (NIF), which is the size of three football fields. According to the website of NIF,

“NIF is the world’s most precise and reproducible laser system. It precisely guides, amplifies, reflects, and focuses 192 powerful laser beams into a target about the size of a pencil eraser in a few billionths of a second, delivering more than 2 million joules of ultraviolet energy and 500 trillion watts of peak power, [generating] temperatures in the target of more than 180 million degrees Fahrenheit and pressures of more than 100 billion Earth atmospheres. Those extreme conditions cause hydrogen atoms in the target to fuse and release energy in a controlled thermonuclear reaction.”

Although an extraordinary milestone, the commercialisation of nuclear fusion technology will face several resources and technological constraints that are worth considering, a popular YouTube channel Real Engineering, explained these constraints in their latest video:

Current fusion reactors combine two isotopes of Hydrogen: Deuterium (2H) and Tritium (3H), to produce Helium (4He). Although the supply of Deuterium (also called heavy water) is abundant as it is found in seawater, Tritium is a relatively rare isotope sourced primarily from nuclear reactor moderator pools where heavy water gets radiated to produce Tritium. This is a major constraint as the current supply of Tritium would significantly outstrip the demand from commercial fusion reactors, with the limited scope of increasing production.

Lithium can be used as an alternative source of Tritium as it undergoes fission to produce Tritium and Helium. However, this process requires materials made of Beryllium which is a rare and extremely expensive element. There are also safety concerns due to the presence of trace amounts of Uranium in this material.

The video explains these and a few other challenges that the commercialisation of nuclear fusion would face. The path from technological breakthrough to commercialisation is a tough one, but the video ends on a hopeful note. This piece by Charles Seife in The Atlantic is also cautiously optimistic about the breakthrough while detailing the history of NIF and its several fusion experiments.

Share this post