Antariksh Matters: Tying commercial and military ends

— Pranav R Satyanath

Eight months after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, it is an established fact that commercial entities in space provide a vital service for enhancing military capabilities. The Ukrainian military purchased hundreds of images from companies like Maxar and Planet to monitor Russian formations. More famously, internet services provided by SpaceX’s Starlink constellations proved vital for soldiers on the battlefield. Other companies, like HawkEye 360, offer services that warn the Ukrainian military of potential GPS interference.

My colleague Aditya Ramanathan and I have extensively covered the issues of using commercial satellites for military purposes. After all, we covered Starlink and Russian attacks in the previous edition. The problem of commercial-military satellite entanglement, however, is indispensable. On Thursday (October 27), Russian officials warned that Western commercial satellites could be legally targeted if the United States and its allies continue their involvement in the war in Ukraine.

As mentioned in previous Technopolitik editions, Professor Davi Koplow has made a robust case for legally targeting space assets. He argues that any space asset that assists a country’s military operations could be legally targeted under the Law of Armed Conflict. Others have highlighted the importance of proportionality of attack under International Humanitarian Law and the need to take into consideration the possibility of indirect harm towards civilians during armed conflict.

The issue that I raise here is more novel. I ponder the connection between the US-Russia bilateral noninterference agreement with National Technical Means (intelligence-gathering assets, including spy satellites) and the Law of Armed Conflict. Let’s begin with National Technical Means (NTM)). During the Cold War, the US and the Soviet Union wished to limit the number of nuclear weapons deployed on either side. While both countries were willing to agree on some limits (starting with the 1972 Interim Agreement and the ABM Treaty under SALT I), neither side showed interest in on-site inspections for verification (this changed much later). Hence, the two sides agreed to verify the treaty using “national technical means of verification”. NTMs not only include satellites but also consist of ground-based radars and telemetry gathering devices. The definition of NTMs is ambiguous on purpose, as they help countries maintain technical secrecy while acknowledging spying tools as legitimate tools of verification.

Early arms control agreements between the US and the Soviet Union also led to the first steps towards space arms control. Article XII (2) of the ABM treaty stated the following:

“Each Party undertakes not to interfere with the national technical means of verification of the other Party operating in accordance with paragraph 1 of this Article.”

Noninterference was codified in the bilateral agreement, which continues to be a norm in the US-Russia New START agreement.

During the Cold War, commercial entities did exist to provide satellite imagery. Even when they did, governments did not use commercial images to verify arms control agreements. Things are, however, a little different today. The National Reconnaissance Office (NRO), which launches and operates US spy satellites, began purchasing images from commercial vendors, signing billions of dollars in contracts. The end-use of these images is unknown. Since one can not conclusively determine whether commercial images are being used for arms control verification, commercial satellites can be considered to be part of NTMs.

So, if companies like Maxar and Planet, which sell images to the NRO, also sell images to the Ukrainian armed forces, does the rule of noninterference apply, or does the Law of Armed Conflict take precedence? The answer, unfortunately, is that we do not know. The phenomenon of commercial-military entanglement is still unfolding. But pondering these questions is essential to keep outer space safe and secure.

Matsyanyaaya #1: What did CCI just do?

— Bharath Reddy

Over the past few weeks, the Competition Commission of India imposed penalties of ₹1,337 crores and ₹936 crores in two antitrust cases against Google.

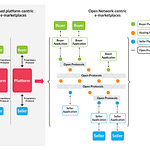

The first was related to Google abusing its market dominance in the mobile operating system and Android app store markets to gain a significant advantage over competitors in other markets. The CCI observed that Google entered into multiple agreements with OEMs that govern their rights and obligations. One such agreement assures that Google's apps, such as search, Chrome and YouTube, come pre-installed on Android devices without an option for users to uninstall them. Other agreements ensure exclusivity of its search services and even prohibit OEMs from offering devices with alternative versions of Android (forks of the open-source code), which are not approved by Google. Access to Google’s Play Store, which is essential to a smartphone, was conditional on complying with these agreements.

The second was related to Google’s Play Store policies requiring developers to mandatorily and exclusively use Google Play’s Billing System for app payments and in-app purchases. This increases costs for users due to the hefty service fees - Apple and Google take a 15 to 30 per cent cut from app developers and also stifles choice and innovation in the payments ecosystem.

These verdicts come close on the heels of Google’s failed attempt to overturn the €4.34 billion antitrust fine handed down by the European Union four years ago. The fines are a little more than rounding errors for a corporation that reported revenue of $69 billion last quarter, but the increasing antitrust cases globally might force them to reconsider their policies.

There are some ostensibly valid reasons for the restrictions imposed in the agreements with OEMs. Having multiple forks of the Android operating system could lead to fragmentation, which could delay security and feature updates. Having a single app store with a gatekeeper could keep unreliable and malicious apps out. OEMs could bundle adware and malware into essential apps such as browsers. While there is a lot of attention and scrutiny about the privacy and anticompetitive practices of big tech companies, there exists a long tail of mid and small-size tech companies which have little to no oversight. Centralisation and control help avoid these risks; however, it hands over control of the entire ecosystem to Google.

Google can leverage the network effects of the Android operating system to gain an unsurpassable advantage in other markets. This is achieved not only through the prominent placement of its apps on Android phones but also through the vast amounts of data about user preferences and behaviour which can be used to improve their offerings. Such self-preferencing and vertical integration are detrimental to competition and limit choice to the end user.

A lot of the issues discussed above are also present in Apple’s iOS and other platforms as well. Big tech companies such as Google, Apple, Meta, Microsoft and Amazon wield enormous power as gatekeepers of their platforms. The EU’s Digital Markets Act which comes into force in May next year, is expected to bring about reforms which will impose obligations on gatekeepers to ensure a level playing field.

Third-party app stores might become a reality ending Apple and Google’s monopoly in app stores, which is also one of the demands made by the CCI. There might be some trade-offs in user freedom and security when this becomes a reality. It is also quite likely that app stores will compete to find a way to balance both of these while also avoiding the exorbitant service fees currently being charged to app developers.

Matsyanyaaya #2: The CCI verdict: All bark and no bite?

— Shailesh Chitnis

It was a busy October for the Competition Commission of India (CCI), India’s antitrust regulator. In a one-two punch against Google, the CCI first fined it $161.9 million for forcing device makers to pre-install Google’s suite of apps and penalising alternate versions of Android, its “open source” operating system. Next, the CCI hit Google with a $113 million penalty for preventing app developers from using third-party payment apps.

The same week, it fined MakeMyTrip, India’s largest travel portal and OYO, a hotel aggregator, a combined $47 million for restricting market access to OYO’s competitors on MakeMyTrip’s platform. Taking all factors together, the decision represents a clear message that the CCI is looking at digital markets and platforms a lot more closely.

But do these actions have wider implications? A hot-take is to compare the penalties to the revenues of the companies and predict that it would hardly have an impact. Most companies appeal the rulings in court, and in the years that it takes for the cases to be resolved, the fines are whittled down. The CCI has also been notoriously ineffective when it comes to collections. Data shows that from 2011-2018, the CCI imposed a cumulative penalty of more than $1.3B but recovered less than 1%.

But that misses the point. The CCI rulings are important because they signal that the regulator is taking a measured approach to competition in the digital ecosystem. Until this point, India had been fair “hands off” with its approach to digital platforms. Part of the reason may have been the size of online markets when compared with offline markets. But the nature of digital markets, especially the network effects, which create outsized winners, makes an intervention in this domain timely.

Second, the CCI also recognizes the limits of its power. In the absence of supporting legislation and the fast-changing nature of this industry, the agency is nudging participants towards corrective action rather than enforcement. Even as Google will likely challenge these rulings in court, it has paused the requirement for developers to use Google Play’s billing system. Treebo and FabHotels, Oyo’s competitors, are back on MakeMyTrip. Market correction, not enforcement.

Finally, the cohort of Google, Meta and others have been used to dealing with regulators around the world. India would be no different. But, for probably the first time in their existence, big tech is vulnerable. The continued slowdown in the ad-tech supported business, coupled with fears of a recession, has created uncertainty over their growth.

Against this backdrop, the CCI’s actions couldn't have come at a worse time.

Our Reading Menu

[Opinion] The US and China are battling for semiconductor supremacy by Pranay Kotasthane and Abhiram Manchi.

[Article] Paradoxes of Intermediation in Aadhaar: Human Making of a Digital Infrastructure by Bidisha Chaudhuri.

[Book] From Mainframes to Smartphones: A History of the International Computer Industry by Martin Campbell-Kelly and Daniel D. Garcia-Swartz.

Share this post