Antariksh Matters #1: India’s Space Policy under IN-SPACe

— Pranav R Satyanath

On 10 June, 2022, Prime Minister Narendra Modi inaugurated the headquarters of the Indian National Space Promotion and Authorisation Centre (IN-SPACe) in Ahmedabad, Gujarat. The setting up of IN-SPACe promises to usher in a new era for India’s commercial space sector, as the organisation is geared to function as a one-stop institution for regulating space activities and providing entities in the private sector access to facilities run by the Department of Space (DOS) and the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO).

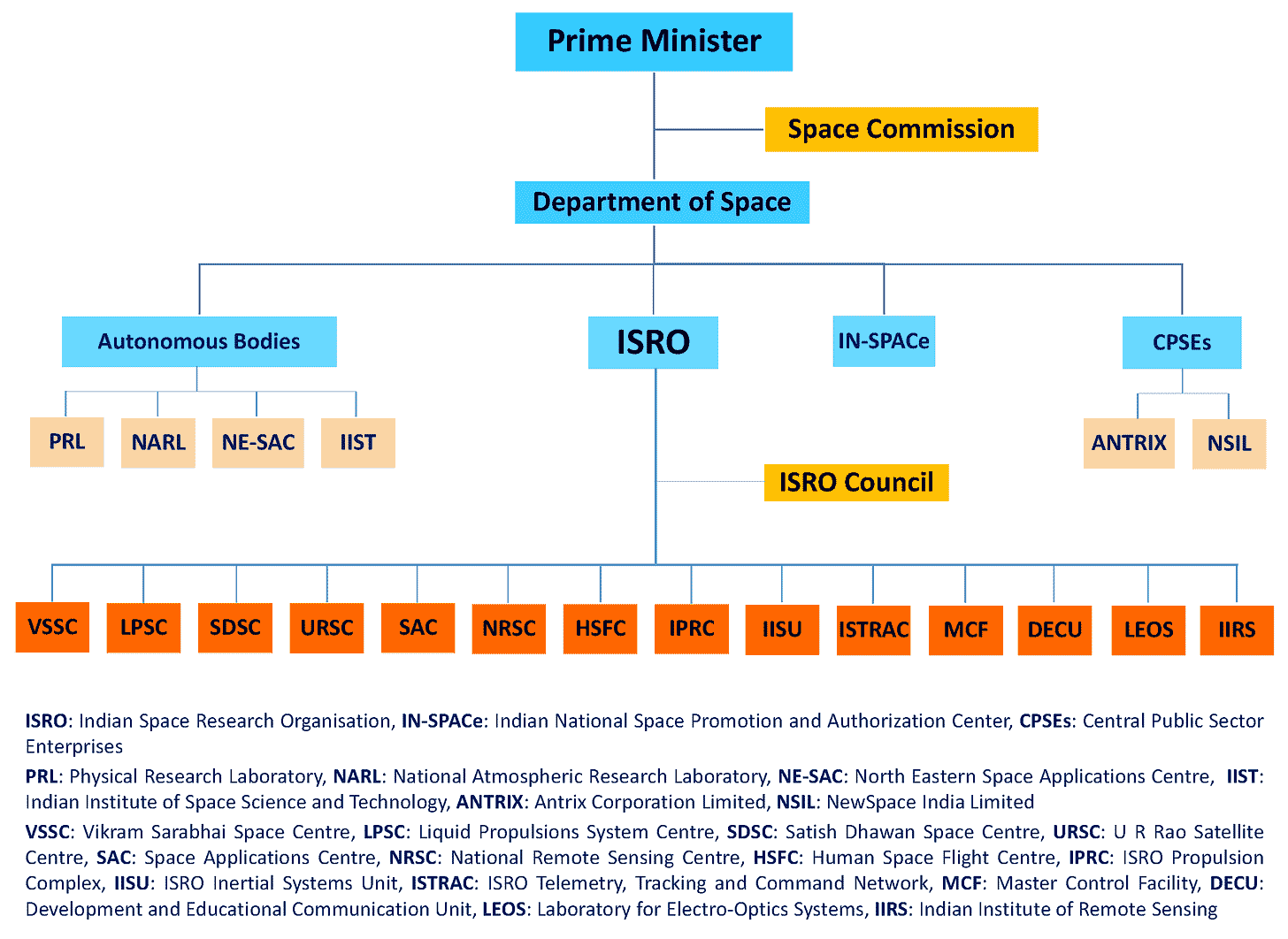

The creation of IN-SPACe was announced in June 2020 within the pages of the Draft National Space Transport Policy published in June 2020, in light of the growing importance of commercial entities for driving innovation in the space sector. IN-SPACe is structured as an independent body within the DOS, and as of this writing, IN-SPACe has authorised two private companies to launch their payloads onboard the PSLV-C53. The structure of INSPACe’s regulatory mechanism is shown below.

Before IN-SPACe

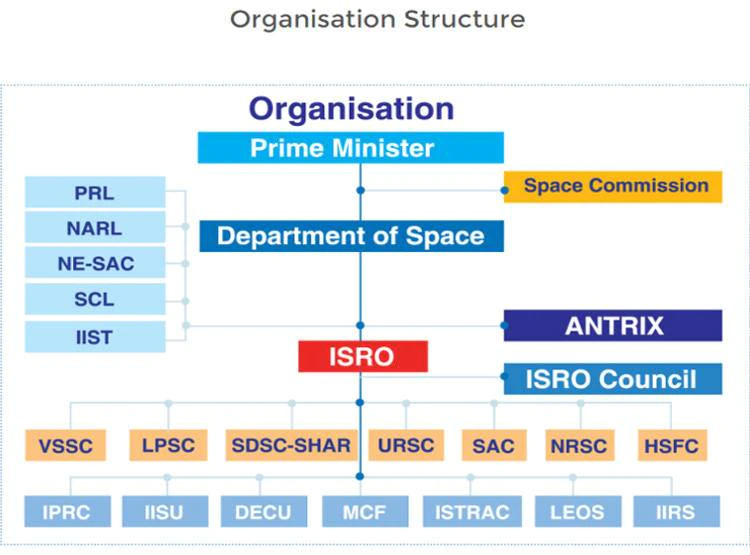

To fully appreciate the significance of a regulatory body like IN-SPACe and identify its shortcomings, we must first see the regulatory arrangement present in India before the coming of this new autonomous body. The image below shows the structure of India’s space enterprise run by the DOS. Under this arrangement, it is clear that the DOS did not have any straightforward mechanism to interact with private space companies or regulate their activities. Since ISRO operated all of India’s launch facilities and a large number of research laboratories, it became a single point of contact for private companies, and therefore, a de facto space activities regulator.

The Structure of India’s space ecosystem prior to IN-SPACe Source: ISRO

As the private space industry in India began to grow, the difficulty of gaining access to gaining critical facilities and services made it all too evident that India desperately needed a new space policy. Further, the international regulatory environment on space sustainability also began to take shape under the Long-term Sustainability (LTS) Guidelines of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (UNCOPUOS). India desperately needed a coherent domestic space policy to keep up with the international standards of regulating private entities and ensuring the safety and security of India’s own space assets. Within this context, the necessity of a new regulatory body for space activities was born.

The Current Structure of India’s space ecosystem Source: ISRO

IN-SPACe now and in the future

The existing structure of IN-SPACe promises a smooth process for private entities to:

Be granted permission to operate.

Be given access to facilities operated under DOS.

Be granted permission to run their own facilities.

IN-SPACe also promises to share technologies and remote sensing data with private companies through a new remote sensing policy. The substance of these promises can only be analysed once the IN-SPACe begins operating in full-swing.

Some of the unintended consequences of IN-SPACe may be that it might act more as a gatekeeper than an enabler. Such risks can be avoided by maintaining the autonomy of IN-SPACe and reducing the role of other stakeholders in the decision-making process. Second, the DOS must eventually ensure that ISRO becomes a scientific research institution and cedes control of its legacy space launch vehicles to New Space India Limited, which must function as a fully private launch entity that competes with other domestic players.

Cyberpolitik: India Needs a Fortified Computing Ecosystem

— Arjun Gargeyas

The advent of the Information Age and the digital economy has brought the concept of computational capacity into the limelight. Advanced computing mechanisms such as high-performance, quantum, and cloud have taken over the field of computing. Nation-states (and even private companies) are embroiled in a high-stakes race to increase indigenous computing power for several strategic purposes. Harnessing this pivotal technological resource remains a priority for a rising technological society like India. With the country’s data generation at an all-time high, there is a need for improving the computational capabilities of the state by utilising emerging advanced computing technologies.

The announcement of the National Supercomputing Mission (NSM), in 2015 by the government of India, was the first step taken by the state in the field of High-Performance Computing technologies. A jointly funded programme between the Department of Science and Technology (DST) and the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MeitY), a total outlay of Rs 4500 crore has been allocated for the mission over a period of 7 years (2016-2023). The main objectives of the mission were to spearhead research in the development of supercomputers and build a National Supercomputing Grid across the country.

The implementation of the mission was divided into three phases. The first involved assembling supercomputers in India (till the end of 2018) and the second was meant for designing these high-performance computing solutions in the country (completed by September 2021). The final phase, which has officially commenced, involves the indigenous design and manufacturing of supercomputers in the country.

Till the end of February 2022, there have been 10 supercomputers installed at various host institutions under the mission. However, considering the distribution of the top 500 most powerful supercomputers in the world, India accounts for just 0.6% of the total. While the national mission has kick started work in the field, there is a long way to go before India can develop its own interconnected structure of supercomputers.

The other major advanced computing technology dominating the market is quantum computing. While India has a dedicated supercomputer programme in the form of NSM, there has been no dedicated government policy towards the field of quantum computing specifically. However, the domestic private sector has gotten involved in the development of quantum computing hardware, software, and algorithms. The government has relied on partnership deals with major private firms to advance the quantum computing landscape in the country.

In 2021, the government of India announced tie-ups with technology giants, Amazon Web Services and IBM India to improve access to a quantum computing development environment for the industrial and the scientific community. This led to the establishment of the Quantum Computing Applications Laboratory to build small-scale quantum computers. The establishment of the Greater Karnavati Quantum Computing Technology Park (GKQCTP), by the government of Gujarat and a research firm, Ingoress looks to house the country’s first-ever quantum computer.

Recent progress by the state in the computing domain has showcased the government’s intent to view computational capacity as a strategic tool to possess. However, the headway has been slow and adequate measures have to be taken to ensure India does not fall behind the pack. A holistic strategy is needed to facilitate the advancement in the computing field.

First, the ability to build advanced computing devices and facilities rests on a wide range of components and raw materials. It would be impossible for any state, let alone India, to indigenously manufacture the whole system from scratch. This is where the reliance on high-tech imports kicks in. Trade barriers such as export control mechanisms and import restrictions that still exist can hamper access to the building blocks of these systems. For example, advanced processors for supercomputers and cryogenic cooling systems for quantum computers are a necessity. But with existing export controls, indigenously developing them will take time for India. Cutting down on import tariffs, especially in the electronics sector, along with embracing multilateral trade agreements like the Information Technology Agreement (ITA 2015) must be the government’s priority. Moving towards a liberalised trade policy that embraces tech imports can help the country accelerate its computing programmes.

Second, there needs to be a more holistic vision for developing a nationwide computing grid. China’s recently announced National Computing Network can serve as a blueprint for India to scale up its computing infrastructure. The Chinese plan talks about a geographical approach to building data centres and computing clusters across the mainland. The concept of ‘Data from east, Computing in the west’ has been proposed, which involves the setting up of computing architecture in the less developed western regions of the country to handle the data stored in centres already established in the tech-aligned eastern region. A computing grid in India can follow a similar pattern with computing clusters scattered across the country. Till now, the government has focused on academic and scientific research institutions as hosts for large-scale computing systems. Dispersing these facilities across other locations can enhance and coordinate regional development also. Creating a better network can improve the functioning and efficiency of an advanced computing grid as well as handle large-scale data processing with ease.

Third, looking at the need to increase computing power from a military and strategic perspective can improve the computing technology being used currently. In an age of information warfare and cybersecurity threats, increased computational capacity is a necessity and a risk mitigation tool. Advanced computing facilities at strategic environments like naval bases, air command control centres and border outposts can help in the faster analysis and real-time data processing that contains critical military intelligence. India must focus on its computing strategy keeping in mind the defence and national security angle. Countries like the US and China are looking at advanced computing systems to simulate military operations and gain key advantages. India needs to leverage its computing capabilities effectively for defence and cannot afford to remain complacent in this domain.

(An edited version of this article came out in the Hindustan Times on 10th June 2022))

Antariksh Matters #2: The UK Wants to be a Big Spacefarer

— Aditya Ramanathan

On 23 June, the UK’s minister for science, announced four sets of proposed plans that he said were intended to encourage sustainable use of space. The minister, George Freeman, unveiled the UK’s Plan for Space Sustainability during a talk at the latest edition of the Summit for Space Sustainability, which is hosted by the US-based Secure World Foundation and the UK government.

The first of Freeman’s proposed plans is to strive “to lead in the global regulatory standards for orbital activities”. The second is to pursue international cooperation in the sustainable use of space. The third is to create what Freeman called “simple, accurate metrics” to gauge space sustainability. The fourth is to create a debris removal programme.

The UK’s Outsize Ambitions in Space

The UK has been a particularly active participant in international debates around space governance, sustainability and security. Last year, it released a national space strategy and in February of 2022, it published a defence space strategy. It was an early signatory of the US-led Artemis Accords that seeks to lay out ground rules for lunar exploration and commercial use. The UK was also a key driver behind the setting up of an Open-Ended Working Group (OEWG) on space threats, which completed its first meeting in May.

Commercial concerns are at the heart of the UK’s activism. Freeman’s own remarks at the Space Sustainability Summit made clear the UK’s ambitions:

“As it was with shipping in the 17th century and cars in the 20th, the key will be regulation which enforces good industry standards and reduces the cost of insurance and finance for a satellite launch which can show it is compliant. With London as a global capital of insurance and venture financing, we have an opportunity to use our historic role in space science to now harness responsible finance for sustainable space.”

While Freeman’s comments implicitly evoked the legacy of the UK’s historic maritime power, they are in line with the goals of the national space strategy, which set out five goals:

“Grow and level up our space economy

Promote the values of Global Britain

Lead pioneering scientific discovery and inspire the nation

Protect and defend our national interests in and through space

Use space to deliver for UK citizens and the world”

The UK’s own space industry is small but growing. According to a report commissioned by the UK government, space-related companies and organisations generated income of £16.5 billion in 2019-2020, a third of which came from exports. Space applications constituted the biggest share of this income, at £12.2 billion, followed by space manufacturing which accounted for £2.27 billion.

The UK evidently hopes to see this industry grow much larger, but there will be some challenges ahead. While the UK will benefit from its special relationship with the US and traditional ties with Europe, it will face commercial competition from both geopolitical friends and foes. Its ambitions to set regulatory and legal standards are also likely to be contested by China and Russia. And even small-sized rivals like Luxembourg could market themselves as more attractive destinations for the registration of space companies. Notwithstanding these challenges, the UK’s activism also offers a model for other states like India. Freeman is yet to provide details of the proposals he outlined, but there’s no reason India cannot develop proposals of its own, outline a national space strategy, or actively participate in ongoing talks on space security.

Our Reading Menu

[Opinion] How India Can Take a Leaf Out of China’s Playbook on Battery Swapping to Form a Robust EV Ecosystem by Rohan Pai.

[Report] Boost-Phase Missile Defense: Interrogating the Assumptions by Ian Williams, Masao Dahlgren, Thomas G. Roberts and Tom Karako.

[Research Article] Echo Chambers, Rabbit Holes, and Algorithmic Bias: How YouTube Recommends Content to Real Users by Megan A. Brown, James Bisbee, Angela Lai et. al.