Cyberpolitik: Invasion and Infektion

— Prateek Waghre

In a recent edition of The Information Ecologist, I had referred to the activity around the IStandWithRussia and IStandWithPutin hashtags that seemed to include a number of accounts associated with India.

The second India subplot is the presence of seemingly India-associated accounts in Twitter trends such as ‘IStandWithRussia’ and ‘IStandwithPutin’. See this thread by @NovelSci and these threads by (1,2) by @MarcOwenJones.

Since then, we’ve had more investigations looking into this aspect.

A DFR Lab investigation observed [Jean Le Roux - DFRLab]:

The Top 12 most retweeted tweets belonged to accounts with low follower counts. Despite this, they seemed to gain very few followers. In some cases, accounts started sharing some of these tweets within minutes of their creation (an example in Jean Le Roux’s post references an account that shared 3 of the top 12 tweets within 2 minutes of being created) even though they didn’t follow any of these accounts. If you head over to the post and look at the collage of these tweets, many of the handles appear to have ‘Indian-sounding’ names.

“A large portion of the sampled accounts appeared to originate in India”. How? (one should bear in mind that OSINT analysis often requires making a lot of educated guesses)

Language cues, tweets about local sports and politics, early follows (likely region-based suggestions), and the time zone in which the accounts were most active all pointed towards India as the origin of many of the accounts in the network.

And that a “large proportion” of the accounts were created this year, and Feb 24th and Mar 2nd were the dates on which the most accounts were created.

Let’s revisit the ‘appeared to originate in India’ aspect.

While Marc Owen Jones’ sample of 20000 tweets referenced India as a frequently appearing user-reported location (though, in that sample, it wasn’t right on top), he cautions that just because a location is reported does not mean it is accurate.

Last week, the New York Times published an investigation based on data from Marc Owen Jones (I assume more data was collected since the article mentions a 2-week period) [Kate Conger, Suhasini Raj - NYTimes]. (emphasis added, I also wish there were fewer blues, it was hard to differentiate between the other countries)

Users who said they were from India made up nearly 11 percent of the hashtag trend in the two weeks after the invasion. Just 0.3 percent were from Russia and 1.6 percent from the United States during that time.

Around the time Technopolitik 21 went out, Carl Miller posted a network map which indicated that many replies/mentions were directed at accounts in India (if you zoom in, you’ll see accounts of some minsters, Indian embassies, opposition figures and media houses). Worth noting that this map appeared to be account-specific and not hashtag-specific.

Aside 1: One of the network maps on Jean Le Roux’s post did mention Indian and Russian diplomatic accounts (image link).

About 10 days later, Carl Miller posted a map that sub-categorised them based on language clusters, followed by a white paper on March 25th.

Aside 2: If you’re wondering why I was sketching out a timeline, it is because there was a minor subplot developing. Both the tweets I’ve included here reference an information operation. However, researchers like Shelby Grossman (tweet) and Emerson Brooking (replies) pointed out that they provide no evidence of a coordinated information operation.

The white paper, when it came out, didn’t call it a single information operation, either. However, it did make for an interesting analysis. It also highlighted that the information ecosystem is a couple of degrees more complex than we assume and that the way we answer questions like ‘who is winning the information war?’ are influenced heavily by who is asking and what part of it they’re looking at (like the parable about the visually challenged people and the elephant).

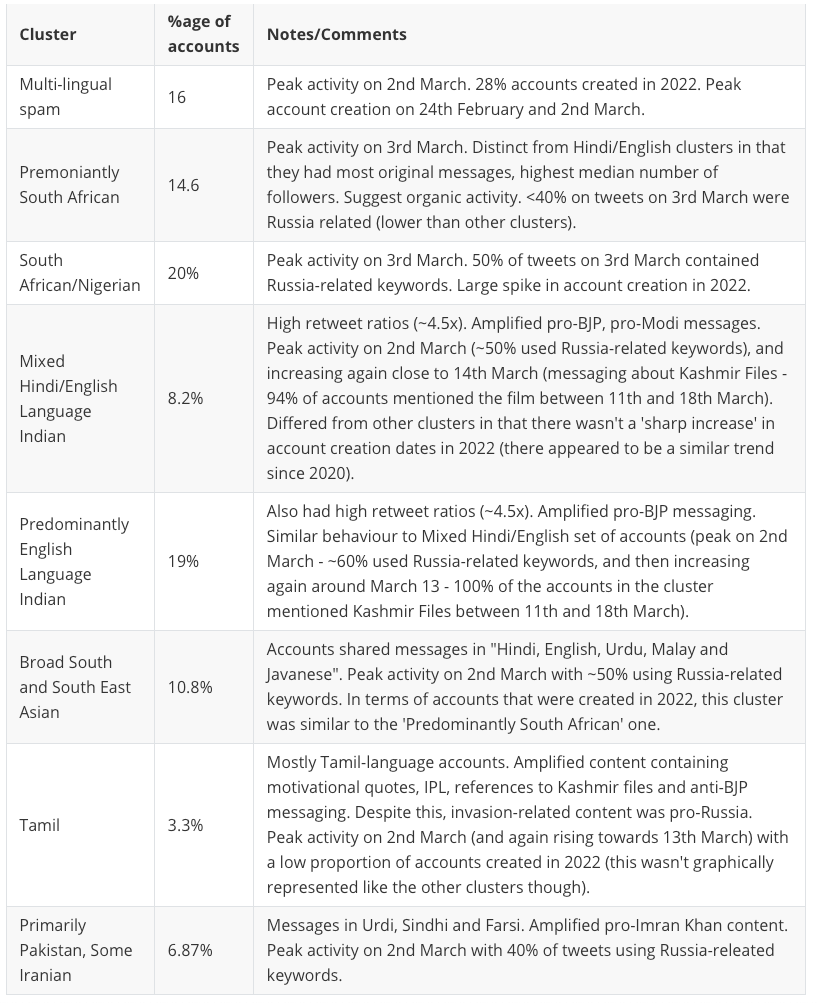

While I can’t speak authoritatively about the research methodology and the clustering of accounts based on linguistic similarities, I’ve included an image with some of my notes from the white paper.

Two dates pop up frequently, 24th February (the day the invasion began) and 2nd March (the date of the UN General Assembly vote and ultimately a resolution which “demand[ed] that Russia ‘immediately, completely and unconditionally withdraw all of its military forces from the territory of Ukraine within its internationally recognized borders.’” [UN.org])

Here’s what the white paper said about the mixed Hindi/English cluster.

We also observe that Russia-related message decreases sharply after the UN vote, but overall volumes of messaging does not. Our speculation is that many of the RED accounts are members of a ‘paid to engage’ spam network that can be rented to supply amplification to a number of different clients, and has over our time of study been used to amplify BJP politics, a commercial cinema release and also the invasion of Ukraine.

This is not surprising. It still doesn’t answer the question of who paid, of course, which would require a tremendous amount of investigative work to establish a clear money trail.

Do friends target friends with information operations?

While we may never find who paid for the Indian-language clusters’ amplification of pro-invasion messaging, it is worth taking a queue from Mike Caulfied’s tweet thread and looking at history.

Chapter 22 of Thomas Rid’s Active Measures references a Soviet Active Measure trying to create the narrative that AIDS was a bio-weapon created by the US (that should sound familiar for many reasons) that had an Indian connection. As per the source material he cites, it was, at some point, code-named Operation INFEKTION by the HVA (the foreign intelligence branch of East Germany’s Ministry for State Security).

“AIDS may invade India: mystery disease caused by U.S. lab experiments.” So read the sensational first-page headline in Patriot, an Indian newspaper, on July 16, 1983. Patriot, under a picture of five smiling girls, printed an anonymous letter from a “well-known American scientist and anthropologist.” There was no name in the byline, only “New York.”

The Patriot letter was a masterfully executed disinformation operation: comprising about 20 percent forgery and 80 percent fact, truth and lies woven together, it was an eloquent, well-researched piece that gently led the reader, through convincing detail, to his or her own conclusion.

He points out that The Patriot had been funded by the Soviet Union, when it opened in 1962, “for the explicit purpose of circulating Soviet-friendly stories and publishing disinformation”. And while the article did not seem to have any direct impact (Rid notes that neither was it picked up in India, nor was it noticed in Europe and the US), it did play a role later:

In KGB's efforts to further a narrative in coordination with partners code-named Denver (in 1985).

The point of departure of the planned active measures campaign, as the KGB told its Soviet bloc partners, was the “factual” article published in Patriot. The KGB then instructed its partners to help spread the theory that AIDS was U.S.-made to “party, parliamentary, social-political, and journalistic circles in Western countries and the developing world.” The “facts” published in the Indian press offered the blueprint

In October 1985 - it was attributed as a source in another article that, as per Rid, would prove to be consequential in the future.

On October 30, Literaturnaya Gazeta ran the headline “Panic in the West: or, What Is Hiding Behind the Sensation Surrounding AIDS.”23 The paper was the KGB’s “prime conduit in the Soviet press for propaganda and disinformation,” according to Oleg Kalugin. The piece that relaunched the DENVER campaign closely mirrored the earlier measure in the Indian press. Its author, Vitaly Zapevalov, accurately cited details about the new disease and its spread in American cities over the past two years, basing his analysis on authoritative U.S. news reports.

“Why,” he asked ominously, would AIDS “appear in the USA and start spreading above all in towns along the East Coast?” Next, the Gazeta piece outlined several covert American biological warfare programs, again based on verifiable public sources. Zapevalov also cited accurate details about Fort Detrick. The author then referred to the two-year-old Patriot forgery to connect the dots. “All of this information, taken together with the AIDS mystery, leads to serious considerations. The solid newspaper Patriot, published in India, for instance, openly expressed an assumption that AIDS is the result of similar inhuman Washington experiments.”

I’ve just quoted specific sections here, I recommend reading the complete chapter (and perhaps the whole book).

So, do friends target friends with information operations? As my colleagues Nitin Pai and Pranay Kotasthane will tell you - there are no friends in international relations, only interests.

Antariksh Matters: Russia, Ukraine & Space Entanglement

— Aditya Ramanathan

Russia’s war with Ukraine is testing a key feature of any state’s military space strategy: entanglement.

Entanglement or intertwining is the act of relying on domestic or foreign civilian space assets to conduct military operations. Days after the war broke out, Ukraine pleaded with commercial satellite operators to share their imagery, especially those from synthetic aperture radars (SAR). In a letter later made public, Ukraine’s minister for digital transformation, Mykhailo Fedorov, wrote that his country “badly needed the opportunity to watch the movement of Russian troops, especially at night”. The minister’s letter made four specific requests:

“Provide high-resolution satellite imagery in the real time to Armed Forces of Ukraine;

Provide data from synthetic aperture radar, or SAR, satellites in the [sic] real time to Armed Forces of Ukraine;

Cooperate with EOS Data Analytics and Max Polyakov as our representative for data processing and analytics;

Stop other types of activities that may support military operations of Russian and Belarus government.”

According to later reporting by The Washington Post, five private companies have already begun sharing such data.

A more stark example of entanglement comes from SpaceX’s Starlink satellite internet constellation. Following a tweet from Fedorov, SpaceX’s Elon Musk made arrangements for Starlink to go live in Ukraine and began supplying the country with thousands of antennas. It has since emerged that Ukrainian forces are using Starlink to facilitate communications and coordinate attacks against Russian forces. As The Telegraph of London reported:

“Drone teams in the field, sometimes in badly connected rural areas, are able to use Starlink to connect them to targeters and intelligence on their battlefield database. They can direct the drones to drop anti-tank munitions, sometimes flying up silently to Russian forces at night as they sleep in their vehicles.”

For Russia, Starlink embodies the dilemmas of entanglement. If this civilian satellite-based communication system is being used for military purposes, does it become a legitimate target? After all, it’s reasonable to argue that, in this case, Ukrainian forces have failed to separate themselves from civilian infrastructure.

There are, of course, practical reasons for Russia not to target Starlink. It is obviously not going to use kinetic weapons such as ASAT missiles against a US-owned target. Even lower-order options like cyber capabilities may either not be feasible, may take weeks or months to develop, or contain escalatory potential that Russia seeks to avoid. For the moment at least, Russia is apparently limiting itself to jamming Starlink signals where possible.

In the years to come, other states may face Russia’s entanglement dilemma, perhaps in starker form. If the Russia-Ukraine war sets a precedent of impunity - essentially leaving space alone as some sort of ‘sanctuary’ - it could encourage other spacefaring states to deepen their own entanglements and share those capabilities with other states at war.

If you enjoy the contents of this newsletter, please consider signing up for Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy(GCPP) Programmes.

Click here to know more

Matsyanyaaya: Can Crafty Fintech help De-Dollarise

— Aditya Pareek

Unprecedented sanctions, restrictions and export controls are inflicting enormous costs on Russia’s economy in the wake of the ongoing conflict. As many large Russian banks have been cut off from SWIFT and conducting business in the US dollar, there is a lot of buzz around the prospects of a new de-Dollarising nexus emerging between Russia and China. In a recent research note, Anupam Manur and I explored the question if Central Bank Digital Currencies(CBDC)s can help them circumvent and cushion the blow of US sanctions.

Russia and China have both sought to ban and discourage the use and mining of private cryptocurrencies, citing both financial stability and security concerns. The two have instead chosen to adopt blockchain technologies for their central bank-issued-and-regulated digital currencies. These Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDC)s have no inherent advantage compared to electronically transferred denominated sums in paper fiat currency counterparts as far as international trade is concerned. As a tool to circumvent sanctions, CBDCs could be theoretically effective in avoiding the US banking system. However,the willingness of another party to accept the CBDC may not always be certain. The value of a currency,whether it be digital or paper,comes from it being widely accepted, which is an uncertain variable at this juncture.

Furthermore, holding CBDCs issued by an isolated and sanctioned nation may not be a desirable prospect. The pariah status of the sanctioned states limits the holder of the CBDC to only conducting transactions with either the issuing states or a small number of other states who might also accept it. Depending on the international political environment, the holders and accommodators of the pariah nation’s CBDCs could also be at the receiving end of secondary sanctions by the international community, further reducing their desirability. The exchange rate volatility and other associated risks will still apply to Russian and Chinese or any other CBDCs, thus, they make little sense in revolutionising the paradigm of international trade in their current form. The CBDCs could be used to settle a limited set of transactions, for instance,India’s defence deals with Russia, which are not a regular day on day or month on month feature.

Furthermore, even if fintech solutions and alternatives exist to some problems, cooperation between Russia and China has always been lopsided, benefiting China above and beyond.

A clear example of this lopsided cooperation is the adoption rate of China’s payments messaging service Cross Border Interbank Payments System (CIPS),to which over 23 Russian banks have subscribed. Meanwhile, only one Chinese bank has signed up for Russia’s equivalent System for Transfer of Financial Messages (SPFS). China is also likely to insist on conducting the transactions and any financing predominantly in the Yuan, as a key strategic goal for China is to make Renminbi a reserve currency alongside the US Dollar.

To know more about how a de-dollarising nexus between Russia and China may be a mirage, check out the full text of the research note here.

Our Reading Menu

[Report] Secure World Foundation’s Annual Global Counterspace Capabilities Report

[Report] CSIS’s Space Threat Assessment 2022 report

[Report] Arms control in outer space: Status, timeline, and analysis By Jessica West and Lauren Vyse

[Opinion] Charting a course for India’s Arctic engagement by Aditya Pareek and Ruturaj Gowaikar who are also contributors to this newsletter

Share this post