CyberPolitik #1: When can Governments Snoop on your Personal Data?

— Sapni G K

Over the past couple of weeks in this newsletter, we have covered the varying aspects of benefits that DCNs bring us. In earlier editions, we covered the harms that are associated with DCNs. Personal data and its governance has been a recurring theme within both these analyses. In addition to the dynamics of private entities dealing with data, it is important to consider government access to data. After all, open-source intelligence (OSINT) already gives away a lot of sensitive information to private, state, and non-state actors. In this context, the might of the state must not be misused to exploit the availability of large quantities of personal data.

There are no agreed international standards on government access to data yet. Broad principles such as respecting the privacy of individuals and the business interests of companies are acknowledged. In 2020, the OECD embarked on an initiative to formulate common principles on the basis of which governments could access personal data held by private companies for national security and law enforcement purposes. Such conversations becomes crucial as invasive products such as the Pegasus snoopware become widely avaialable.

Theodore Christakis, Kenneth Propp, and Peter Swire wrote about the developments in this sphere in Lawfare. It highlights practices employed by governments to access personal data held by private companies. Practices such as the purchase of personal information from data brokers are inimical to trust in government processes. The use of direct access methods, such as hacking, also weakens legal provisions. The challenge, therefore, is to identify reasonable steps that can help maintain the rule of law and provide some protection to citizens.

The group tasked with identifying principles appear to have broadly come to a consensus on the following seven principles:

Legal bases: that law enforcement acts only within a clearly established legal framework.

Pursuit of legitimate aims: that such a legal framework ensures that the scope of data acquisition and use is consistent with narrow, specified purposes echoing the idea of proportionality.

Requirements for approval: that such framework has procedural safeguards for government access requests that respect individual rights.

Handling of personal data: that the handling of personal data is commensurate with principles of minimisation, maintenance of data integrity and security, and minimal retention.

Transparency: that such framework be as transparent as is feasible.

Oversight: that a range of oversight mechanisms be provided to abate non-compliance and provide remedies for the same.

Redress: that effective redress in the form of independent courts and impartial entities be provided by the legal framework.

The conversations at the OECD are currently stalled due to disagreements between two factions. One faction, which included the US, is arguing for immediate consensus on all concerns barring direct access. The other faction, led by the EU, wants more comprehensive coverage by including direct access methods such as hacking and espionage. Even if a consensus is reached, it will remain non-enforceable, as OECD instruments are non-binding. However, when multiple countries across the globe are thinking of revaluating their surveillance and personal data protection regimes, these developments are worth noting.

CyberPolitik #2: In Apple, CCI Antitrusts?

— Prateek Waghre

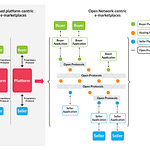

Back in September 2021, a non-profit called Together We Fight Society (TWFS) had filed a complaint against Apple for its app store practices, with the Competition Commission of India (CCI). The specific charges were unknown at the time, but Medianama (paywall) had a deep dive into the complaint. On the eve of 2022, CCI issued an order in the case, instructing the Director-General (DG) to carry out a more detailed investigation. As actions from antitrust regulators/watchdogs around the world continue to pick up steam (aside: Channele2e attempts to track them by country and company), it is instructive to look at the this initial ruling by India’s antitrust regulator. It is worth noting that CCI is also currently investigating Google/Alphabet and Whatsapp. But we’ll look at those cases in future editions of Technopolitik.

While these investigations are fairly intensive processes, at a high-level an antitrust complaint should do the following:

Define a relevant market.

The complaint defined 3 markets. Medianama’s deep dive notes:

1. The market for non-licensable smart mobile device operating systems in India: This market includes smartphone operating systems that cannot be licensed by third-party original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). Apple’s iOS falls under this. It is different from the licensable smart mobile devices operating system market under which Android falls. This key distinction makes it easier for the complainant to establish market dominance.

2. The market for app stores for Apple iOS in India: This market comprises all the channels through which developers distribute their apps to iOS device users.

3. The market for apps facilitating payment through UPI: This refers to the market for apps that enable UPI payments, but the complainant does not provide any rationale as to why this market is of interest in this particular antitrust case.

Make the case for the firm’s dominance in that market. The 1st and 2nd market definitions in the complaint essentially narrow down the market to Apple’s App Store, where it is the only firm.

Prove that the firm has abused its dominance.

Broadly, the complaint alleged that:

Review guidelines on the App Store are arbitrary.

The 30% commission that Apple charges on in-app purchases (IAP) is excessive.

Developers are forced to use IAP as the only method for payment processing, along with a number of other restrictions.

Notably, Apple had contested these relevant market definitions on the grounds that they are too narrow. They also cited market research data from IDC which put Apple’s share at 0-5% of the smartphone market in India, to counter any assertion that they were dominant. The CCI, however, accepted the definition “The market for app stores for Apple iOS in India” drawing a distinction between the markets for consumers (where Apple’s use of smartphone market share data would have been relevant), and developers. It also said that a prima facie case violating various clauses of The Competition Act, 2002 existed (paraphrased in the table below), which needed to be investigated in detail.

The DG’s investigation will be worth watching out for. Rohan, Sapni and I had also discussed these developments on an episode of All Things Policy that went out earlier this week.

Incidentally, back in September 2021, Reuters had reported that a CCI investigation concluded that Google had abused its dominance in Android.

Antariksh Matters: China tells UN its Space Station Narrowly Dodged Starlink Satellites

— Aditya Pareek

In early December, China apprised the United Nations(UN) and the international community of two separate instances involving near misses between its space station “Tiangong” and US private sector owned communications satellites.

The satellites in question, which were being de-orbited after reaching end of their service life, belong to one of Elon Musk’s SpaceX Starlink mega constellations.

Starlink satellite constellations are generally spread out at altitudes of about 550 km.

Starlink-1095 approached an orbit of 382 km, converging with “Tiangong” in July 2021. Starlink-2305 followed a similar collision course with Tiangong around 21st October 2021. The Tiangong which currently has only its core module “Tianhae” in orbit will be coupled with two more laboratory modules “Wentian” and “Mengtian” which are yet to be launched, by the end of 2022.

Starlink hopes to be a worldwide wireless internet service provider with a constellation made up of tens of thousands of individual satellites.

There are provisions for redressal if any actual damage is caused, under the Outer Space Treaty(OST) of 1967 and the UN convention on International Liability for Damage Caused by Space Objects.

Nothing is specified in any international law or treatise for near misses beyond keeping the UN Secretary General apprised.

In the communiqué to the UN, China has also highlighted that any damage caused by a space object would be the responsibility of the state to which it belongs. Even if the object is owned and operated by a private entity like SpaceX, the responsibility and financial liability would fall solely on the state in which the private company is headquartered.

The UN General Assembly and an Open Ended Working group constituted by it is currently engaged in figuring out “norms, rules and principles of responsible behaviors relating to threats by States to space systems.”

The stated purpose of this process is to create a set of norms that would be accepted by all space faring states. These norms are supposed to bolster co-ordination between states and help avoid close passes and convergences in orbit.

Elon Musk has rejected criticism about the mega constellations SpaceX is deploying in low earth orbit, which already houses a vast number of artificial space objects.

China’s state-backed outlet Global Times has published a unique take on the issue, with Chinese experts opining that the move was meant as a test of China’s Space Situational Awareness(SSA) and collision avoidance capabilities.

Siliconpolitik: The TSMC Question

— Pranay Kotasthane

Taiwan has been front-and-centre of the current moment in semiconductor geopolitics. Last week, there was some more action on this front. An article in the US Army War College Quarterly titled Broken Nest: Deterring China from Invading Taiwan argues that:

China can be deterred from invading Taiwan short of a full-scale war

One of the items in a deterrence package should include an explicit threat that Taiwan would self-destroy TSMC should a Chinese invasion occur.

This is not the first time this argument has been made. Nevertheless, the authors go further than others in developing it. Detailing #2, the authors argue:

If Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company’s facilities went offline, companies around the globe would find it difficult to continue operations. This development would mean China’s high-tech industries would be immobilized at precisely the same time the nation was embroiled in a massive war effort. Even when the formal war ended, the economic costs would persist for years. This problem would be a dangerous cocktail from the perspective of the Chinese Communist Party, the legitimacy of which is predicated on promises of domestic tranquility, national resilience, and sustained economic growth.

This is an interesting thought. Since the purpose is deterrence, two lines of enquiry are relevant here. The first is "would such a threat be a credible one?". The second is "even if such a threat is credible, would it alter China's decision making?"

The authors have tried to address the first question in some detail:

Chinese decisionmakers must absolutely believe Taiwan’s semiconductor industry would be destroyed in the event of an invasion. If China suspects Taipei would not follow through on such a threat, then deterrence will fail. An automatic mechanism might be designed, which would be triggered once an invasion was confirmed. In addition, Taiwan’s leaders could make it known now they will not allow these industries to fall into the hands of an adversary. The United States and its allies could support this endeavor by announcing plans to give refuge to highly skilled Taiwanese working in this sector, creating contingency plans with Taipei for the rapid evacuation and processing of the human capital that operates the physical semiconductor foundries.

In a section aimed at the Taiwanese people and government, the authors recommend:

No doubt the Taiwanese will have grave concerns about threatening China with a defensive war that likely cannot be won. The prospects of implementing scorched-earth and guerilla-warfare tactics will be similarly unappealing. It will therefore be a major challenge to make these threats credible to China, though perhaps not as difficult as convincing Beijing that Taiwan and the United States are willing to risk a great-power war over Taiwan’s political status. Paradoxically, however, it is only by making these threats credible that they will never have to be carried out. In any case, the threats outlined above—even if carried out to the maximum extent—will be far less devastating to the people of Taiwan than the US threat of great power war, which would see massive and prolonged fighting in, above, and beside Taiwan.

I am interested in the second line of enquiry — even if the credibility-enhancing steps suggested are followed, would it change China's decision-making calculus? I don't think so, for two reasons.

Invasion directly implies TSMC's downfall. If such an action is being debated, the costs of losing TSMC will be assumed by China, regardless of a scorched-earth strategy. That's because a China-controlled TSMC would still be dependent on ASML for EUV machines, on Japanese companies for photoresists, and on many US firms for other critical manufacturing equipment. In case of an invasion, all these lines are highly likely to be cut off. Thus, China's decision to invade will rest on the assumption that TSMC becomes a diminished entity in the semiconductor space. If anything, the status quo works better for China where it can poach TSMC engineers to build its own manufacturing industry. A scorched-earth strategy doesn't change China's payoffs from invasion.

TSMC is neither irreplaceable nor indelible in the long run. TSMC's credentials are impressive indeed. But many countries, including China, can replicate its success over time if it were ever to be destroyed. The monetary and opportunity costs would be huge, no doubt. But given a few years, others can catch up. The key ingredients are access to adequate human capital, humungous capital investment, and most crucially continued access to global vendors and customers. And so, an invasion can't be deterred because the economic loss of such an action is temporary and reversible.

For more, read this two-part (1,2) series in The Diplomat by John Lee and JP Kleinhans.

Our Reading Menu

[Article] Three Takeaways From China’s New Standards Strategy by Matt Sheehan, Marjory Blumenthal and Michael R. Nelson.

[Opinion] India Can Take Lessons From China’s Technical Standardisation Strategy by Arjun Gargeyas who is also a contributor to this newsletter.

[Book] Routledge Handbook of Space Law Edited by Ram S. Jakhu and Paul Stephen Dempsey

[Article] Norwegian Undersea Surveillance Network Had Its Cables Mysteriously Cut