Matsyanyaaya: The US-Australia Quantum Tech Agreement

— Arjun Gargeyas

The Quantum race has just heated up. November saw an official agreement between the United States and Australia on quantum technology cooperation. An official statement underlined the importance of science and technology in the information age along with the need for collaborative and transnational efforts in the pursuit of scientific discovery and societal benefit. The statement also described quantum technology, as being a critical and emerging technology that could enable the development of faster computers, secure communication networks, and more accurate sensors.

This new agreement comes at a time when the global quantum ecosystem is developing across the globe with increased participation from different states. This includes the realisation of the field’s benefits with the hope of new quantum-enabled economies coming up.

What does the Agreement Entail?

The agreement goes into the prospects of new theoretical and practical applications of quantum technology along with the translation of credible research in the field into potential applications that would be of mutual benefit to both countries. It also emphasizes the need for joint research and development along with critical technology transfers between the two countries.

There is also a focus in the agreement on building a quantum technology market with the help of the private sector and other industry bodies. The agreement is also a step towards diversifying supply chains in this field.

The agreement delves into the need for improvement in the field of quantum education in both countries. Cross border education in the field can help in fast-tracking significant research in the field and can build a competent workforce for the future. The exchange of skills and development can help in the protection of intellectual property along with building safe and secure research environments. Finally, the sharp focus on quantum technology can help the two states collaborate in developing and setting technical standards that foster interoperability, innovation and transparency.

Other than the objectives of the agreement, there was also a mutual decision taken between the two governments in holding the Quantum Policy Dialogue that would involve senior government officials, who are experts in quantum technologies, meeting regularly to flesh out the subsequent agendas for the cooperation agreement. This would eventually help in the identification of practical initiatives that can be taken forward by both governments.

With China pursuing quantum technology, this agreement looks to be a joint effort between two technologically advanced states to counter their common adversary. The applications of quantum technology are broadening with strategic angles to the technology driving forward this focus. There is still a long way to go before computing power or stable communication networks using quantum technologies can be deployed on a large scale. But the race to achieve what is commonly known as ‘Quantum Supremacy’ has definitely begun. It is something worth watching out for.

CyberPolitik #1: Can Digital Communication Networks have benefits?

— Prateek Waghre

This entry is adapted from one of the sections of a forthcoming discussion document by Prateek Waghre and Sapni GK on the opportunities and benefits associated with Digital Communication Networks.

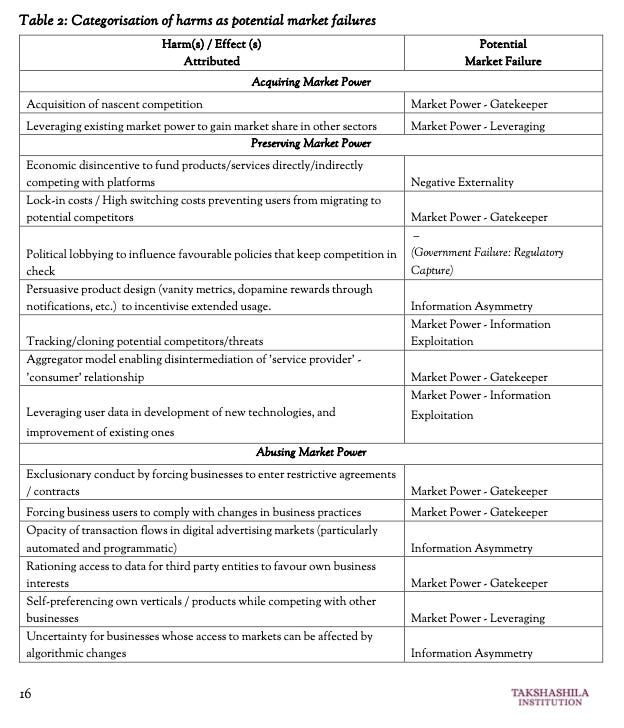

Back in July, we had published a paper categorising the various kinds of harms attributed to Digital Communication Networks as potential market failures, social problems and cognitive biases. I’m including some screenshots from the tables just to give you a sense of it - for the complete tables, do look at the original document.

In the course of writing that paper and a bunch of discussions during and after it on whether benefits are self-evident or not - we also realised that much of the analysis around the benefits/opportunities hadn’t really evolved much since the early/mid-2010s. Maybe we were just looking at the wrong sources… but what we found were either variations of the ‘Democratising Force’/Arab Spring angles or very specific and narrow use-cases.

So we signed off saying:

In subsequent work, we plan to identify the benefits that DCNs enable, assess overlaps and contradictions between proposed/enacted DCN governance measures, and explore the role of global internet governance mechanisms with the aim to define appropriate frameworks to govern DCNs.

This was back in July, mind you, long before the Facebook Files/Papers/Documents sent our heads spinning. Nevertheless, as Dean Eckles points out in his testimony to the US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, and Transportation (on Pages 1 and 5); or as Rebekah Tromble said in this episode of the TechPolicy.Press podcast; or as Rebeca Mackinnon noted in this episode 2 of the Internet of Humans podcast - we don’t have a grasp on the benefits.

So, in a forthcoming paper, we try to list out potential opportunities and benefits in the context of markets and societies. In this section, I’ll write a bit about how we approached their role in imparting social benefits.

One of the things we did in the harms paper was to define the concept of Digital Communication Networks (DCNs).

DCNs as composite entities consisting of:

Capability: Internet-based products/services that enable instantaneous low-cost or free communication across geographic, social, and cultural boundaries. This communication may be private (1:1), limited (1:n, e.g. messaging groups), or broad (Twitter feeds, Facebook pages, YouTube videos, live streaming), and so on.

Operator(s): Firms/groups that design/operate these products and services.

Networks: The entities/groups/individuals that adopt/use these products and services, and their interactions with each other.

And while the term may not ever catch on, its usage was deliberate.

The purpose of introducing a new frame is to encourage the study of DCNs from the perspective of their effects on societies as a whole rather than a specific focus on a specific set of firms, technologies, sharing mechanisms, user dynamics, and so on.

In the context of societies, we tried to focus on the role of capabilities and networks, and not the firms themselves - though, it isn’t possible to always ignore them.

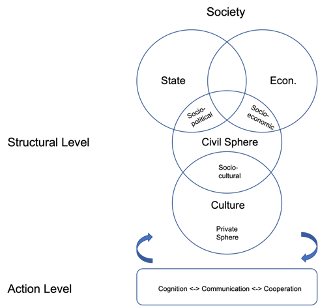

First, we had to try and visualise what societies look like. When attempting something like this, there will always be layers of abstraction - and no model (no matter how good) can perfectly capture systems as complex as modern societies. Nevertheless, we found that the model that Christian Fuchs and Daniel Trottier propose in Social Media, Politics and the State could be a useful one. Some key points from it:

It contains the following subsystems: overlapping state and economic spheres, a cultural sphere, and a civil sphere that mediates the cultural and overlapping state and economic spheres.

The civil sphere is composed of socio-political, socio-economic, and socio-cultural movements.

These movements are struggles for different ends by various social roles within the subsystems.

The Movements are:

Socio-political: For the “recognition of collective identities via demands on the state.”

Socio-economic: For the “production and distribution of material resources created and distributed in the economic system.”

Socio-cultural: Have “shared interests and practices relat[ed] to ways of organising one’s private life.”

The Roles:

Trottier and Fuchs use the tripleC framework to explain that DCNs allow actors to perform tasks of creation (cognition), share them with others who can respond (communication), and modify them (cooperation) in an integrated manner, and that they can all occur in the same social space (capability built by DCN operators).

Then, building on this model, we identify five types of actions that DCNs enable. Note that these are not mutually exclusive. And, in most cases, they overlap. We had to use a non-exhaustive set of examples in the paper to show where DCNs played a role in minimising harms or enabling benefits through a combination of one or more of these actions, since many of these effects could not be quantified.

Information Production/Consumption: Low entry costs and capabilities for users to generate and share content enable participation in DCN Networks at scale. Under this action, we refer narrowly to the ability to transmit information or receive information.

Interaction: Interaction involves receiving and then responding to information. This can manifest itself in various ways. It can mean mutual communication between two or more actors belonging to any of the societal subsystems. This communication can also be directed at a completely different set of actors and may or may not include the original set of actors. Responses need not be limited to communication / sharing on DCN networks but can also include actions taken off them such as physical actions, internalising information, or any of the five kinds of actions identified in this section.

Identity Formation/Expression: Identity formation and expression are complex processes. User profile-centric DCN services provide a natural home for the performance of identity, which itself can lead to the accumulation of social capital. Identities also evolve as actors across the subsystems consume information, interact with information and other actors across DCN networks. These identities (individual or collective) may then be further expressed using DCN capabilities and features.

Organisation: A combination of DCN capabilities and networks reduces barriers for groups of people to cooperate and act towards achieving common or similar goals. They can also aid the scaling phase of self-organising or spontaneous movements. It should be noted that the mere existence of DCN capabilities and networks is not sufficient. The networks also need to include motivated actors with incentives to do so.

Financial Transactions: In this context, we refer to transactions where DCNs play a connective role, and not where the DCN operators are themselves a party to the financial transaction (ad revenue sharing, creator pay-outs, create their own tokens, news partnerships, funds for research and civil society organisations, and so on).

We don’t have a link yet but we’ll include one in the edition right after the document is published.

In the meanwhile, if you want to talk to me about it / see a draft - you can reach out via Twitter DMs (@prateekwaghre) or email me (<FirstName> AT takshashila.org.in

If you like the content of this newsletter consider signing up for our Post-Graduate Programme in Public Policy (PGP). The course is targeted at dynamic individuals who wish to enter the growing professional sphere of policy, public affairs, governance and leadership, while pursuing their current occupations. The PGP equips participants with a core set of skills in policy evaluation, economic reasoning, effective communication and public persuasion.

Siliconpolitik: India’s Semiconductor Strategy Needs to Focus on Five Areas

— Pranay Kotasthane & Arjun Gargeyas

(An edited version of this article first appeared in Hindustan Times on 2nd December 2021)

With a short-term approach of securing a deal to establish a manufacturing facility in the country, the conversation currently solely rests on the path of India’s foray into semiconductor manufacturing. Setting up one fab manufacturing facility won’t significantly reduce India’s strategic vulnerability in the domain.

There is a clear need for a shift in the government approach and a change in mindset at the highest decision-making level to improve India’s position in the entire semiconductor ecosystem. Looking at the experiences of other leading countries in the domain, the time taken to build robust domestic semiconductor industries remains a marathon process. A similar strategy needs to be envisioned for India right now.

First, India needs one 20-year semiconductor roadmap. This needs to begin with an audit of the chips that form the core of key defence equipment and critical infrastructure. Once this vulnerability assessment is done, the government needs to ensure that over time, such equipment should have chips produced end-to-end within the trusted semiconductor ecosystem.

Second, the 20-year roadmap needs a 20-year financial support plan. The roadmap needs to sequence semiconductor initiatives depending on the government’s financial wherewithal. For instance, focusing on getting a leading Taiwanese or South Korean ATMP player to India could be considered immediately, at a lower opportunity cost. Co-investing in a chip production unit at a trailing-edge, speciality chip fabrication unit could then be the next big step for the government. Concurrently, the government can focus on funding new semiconductor materials research, new design architectures for critical equipment, intellectual property protection, and technical standards. Over a two-decade period, this could well give the confidence to global investors to co-invest in a leading-edge fab here.

Three, plurilateral strategic cooperation on semiconductors is a necessity for India, not a choice. The Quad Semiconductor Supply Chain Initiative, announced in the first in-person leadership summit meeting in September 2021, is a good starting point. India now needs to push for a Quad Supply Chain Resilience Fund with the goal of ensuring redundancy in this supply chain to immunise it from geopolitical and geographic risks. For instance, while the US focuses on restarting manufacturing at leading-edge nodes (5 nanometres and below), the group should be able to fund specialised analog, memory fabs operating at trailing-edge nodes (45 nanometres and above) in India, Japan or Australia. Over time, this initiative can coalesce other major semiconductor powers such as Taiwan, South Korea, the EU, and Israel.

Fourth, favourable trade policies are critical for building a plurilateral semiconductor ecosystem. Over the past few years, the union government has been increasing import duties using the rhetoric of Aatmanirbharta. Such policies have major implications on the semiconductor industry globally. For example, even Taiwan, which produces over fifty per cent of contract manufactured chips needs specialised equipment that needs to be imported. Unsurprisingly, a reduction in tariffs was reportedly a major issue of contention in talks between India and Taiwan over a semiconductor collaboration earlier this year. Similarly, considering the nascent domestic market for semiconductor chipsets, foreign entities manufacturing chips in India will primarily be exporting their products. In essence, a fab in India will still be deeply connected with the world — buying equipment from some countries and selling chips to others.

Finally, the 20-year roadmap needs a robust infrastructure plan. Significant quantities of reliable water and electricity supplies are non-negotiable requirements for fabs. It is not possible to meet these specialised requirements all across the country. Fabs will be clustered in a few states that have the risk appetite to get into this sector. Hence, it’s important that the union government works with interested state governments to build the necessary infrastructure.

CyberPolitik #2: Norms for AI - UNESCO’s Recommendations

— Sapni G K

The 41st General Conference of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) concluded on 24 November 2021 with a major step on the global development of norms on the use and regulation of Artificial Intelligence (AI). 193 member states of UNESCO signed and adopted the draft AI Ethics Recommendation. It can be touted as the first globally accepted normative standard-setting instrument in the realm of AI. The voluntary, non-binding commitment is a major point of cooperation in identifying principles of ethics in the regulation of AI systems. This is one step further in conversations that presume the inevitability of AI systems’ involvement in decision making. Consequentially, it could be a first in outlining the foundations of global AI governance. Given the encouragement for multilateral and intercultural efforts, these recommendations appear to be a good starting point for engaging further in the discussions for rulemaking and governance. The structure of the document, dividing the recommendations into values and policy actions facilitates the same.

Values and Value-based Policy

In addition to furthering UNESCO’s longstanding values, the recommendation also suggests policy actions to translate these principles into globally accepted normative standards. It calls for establishing compliance mechanisms to ensure human rights and rule of law are upheld, in consonance with the constitutional provisions of the signatories. It urges the signatories to incorporate ethical impact assessments as part of operationalising AI systems. It nudges states to include a transversal gender impact assessment as part of such ethical impact assessments, which is a welcome suggestion that is seldom raised in conventional conversations around AI ethics. As recommendations spanning the field of AI systems and applications, future policies on the regulation on AI in various specific scenarios, including DCNs, military, and welfare applications can draw from these recommendations.

Geopolitical Significance

Barring China, there is little broad-based regulation of AI that can affect a sizeable population of the world. The United States of America is not a member of UNESCO, which leaves it outside the list of signatories to the recommendation. The European Union’s proposed AI Act hopes to set the norm, repeating the feat achieved by the General Data Protection Regulation in 2017. The new recommendation could be reflected in the path that the AI Act chooses, essentially becoming the normative standard for decades to come. As far as India is concerned, being a passive observer of these developments might not augur well for establishing its interests in the regulation of emerging technologies.

Our Reading Menu

[Paper] International Cooperation in Space Activities amid Great Power Competition by Ludmila V. Pankova, Olga V. Gusarova, Dmitry V. Stefanovich

[Article] Quantum USA Vs. Quantum China: The World's Most Important Technology Race by Paul Smith-Goodson

[Article] Semiconductors – the Next Wave

Opportunities and winning strategies for semiconductor companies[Opinion] AI Strategic Competition, Norms, and the Ethics of Global Empire by Joseph Bouchard