#148 Budget Analysis: Space

In this edition of Technopolitik, Ashwin Prasad analyses the implications of the Union Budget 2026-27 on the space sector. This is part 3 of the Budget Analysis.

🔗 Budget Analysis: AI, R&D, and Innovation

🔗 Budget Analysis: Semiconductors, Cloud Services, and Rare Earth Minerals

This newsletter is curated by Anwesha Sen.

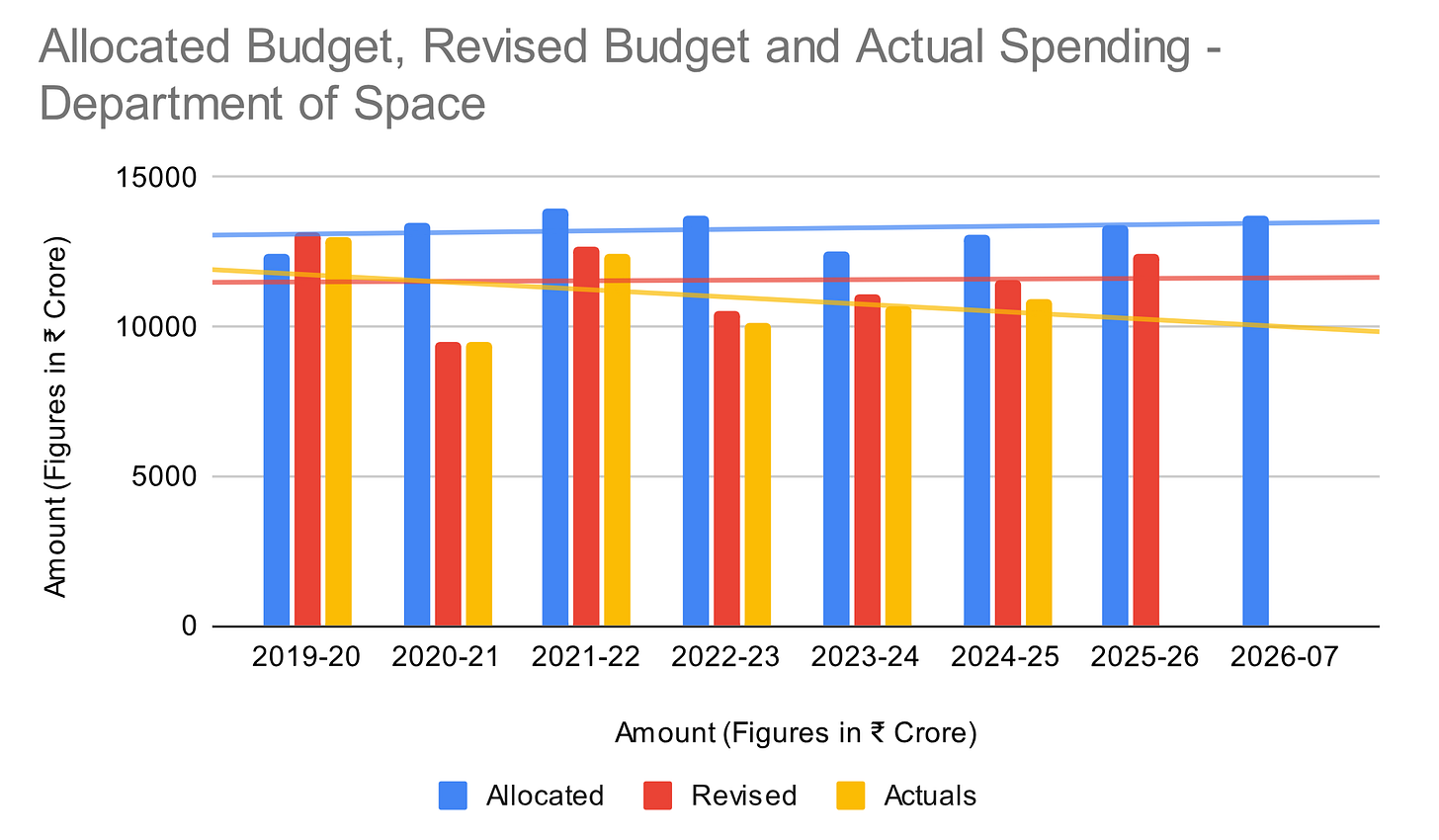

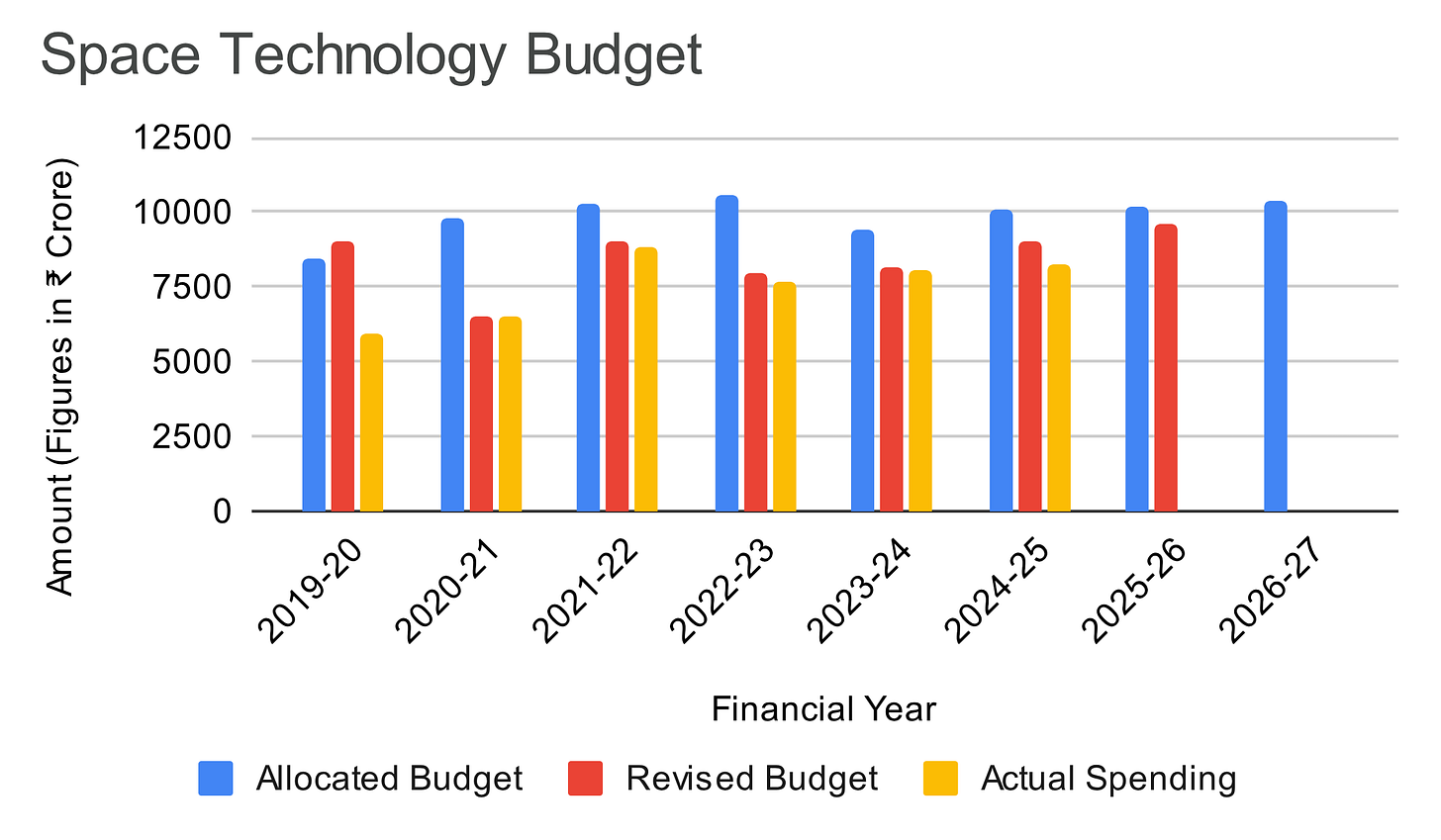

The Department of Space (DoS) has been allocated ₹13,705.63 crores for FY 2026-27. This sits within the ballpark of recent budgets. A deeper look reveals a persistent “under-spending” problem. In fact, since 2020, the DoS has failed to spend even its revised budgets, leaving over ₹12,000 crores unspent. This is effectively an entire year’s worth of funding.

Source: Past budget documents.

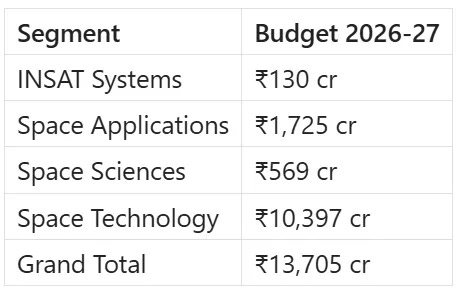

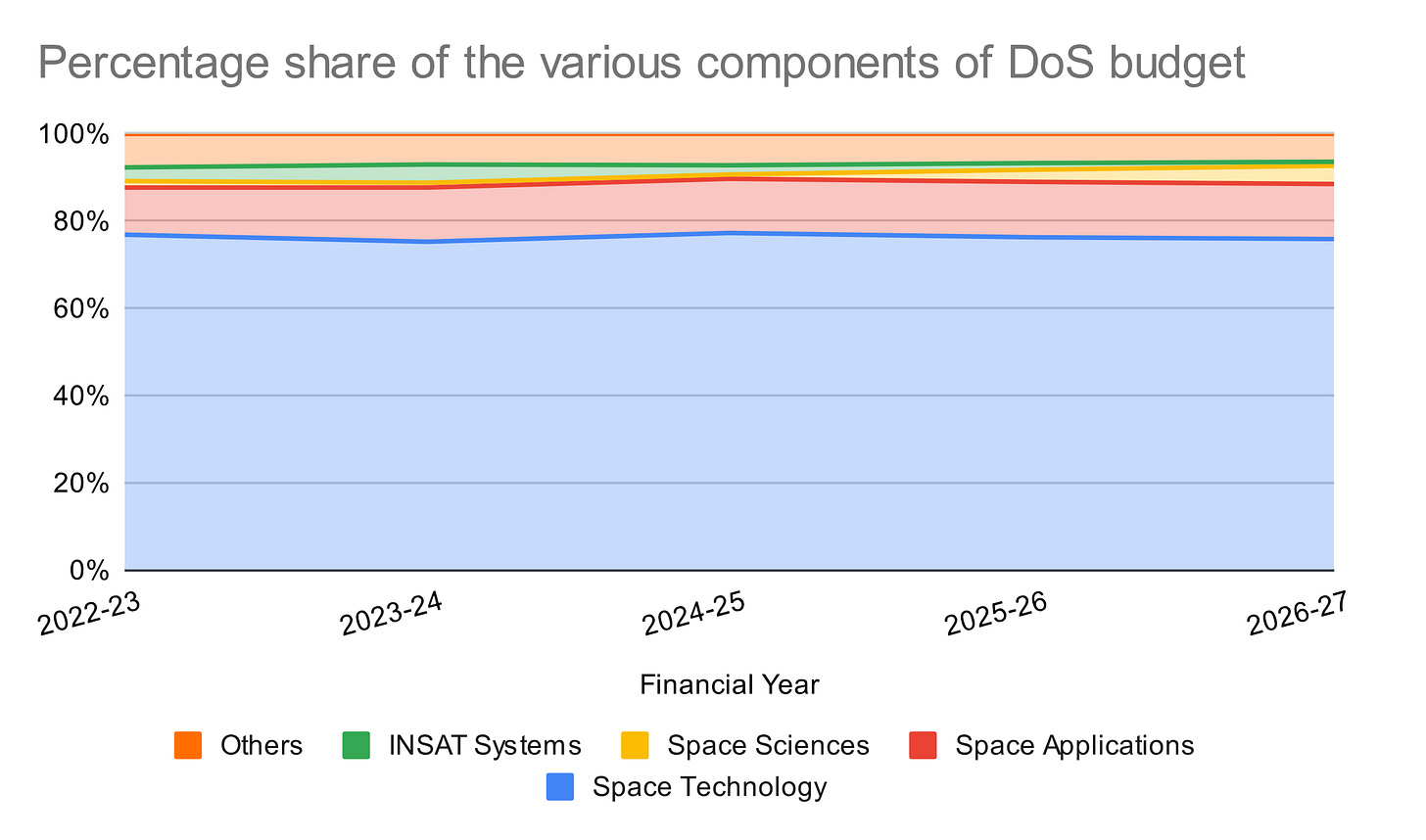

Segment Breakdown

To understand these trends, we can look at the four primary funding verticals:

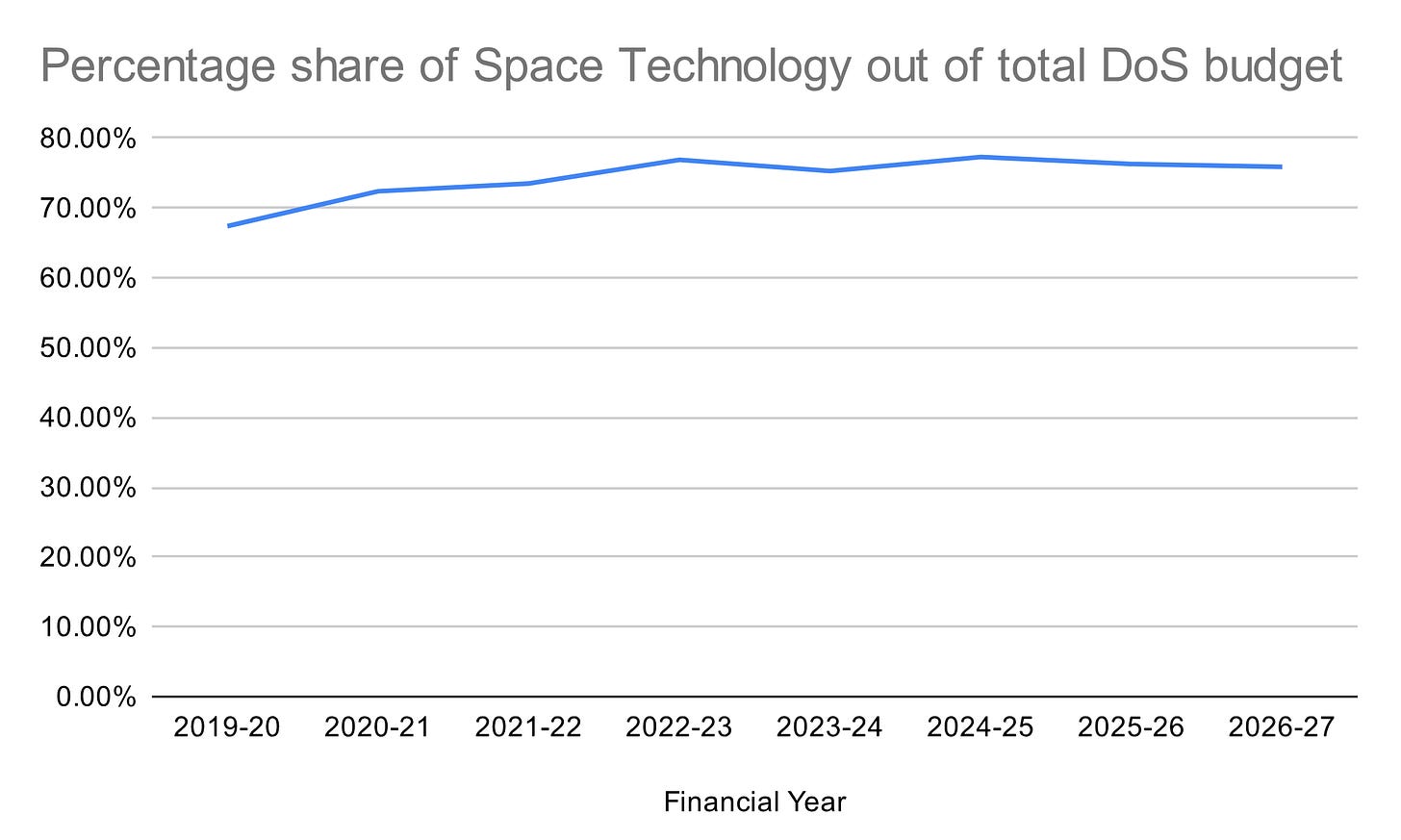

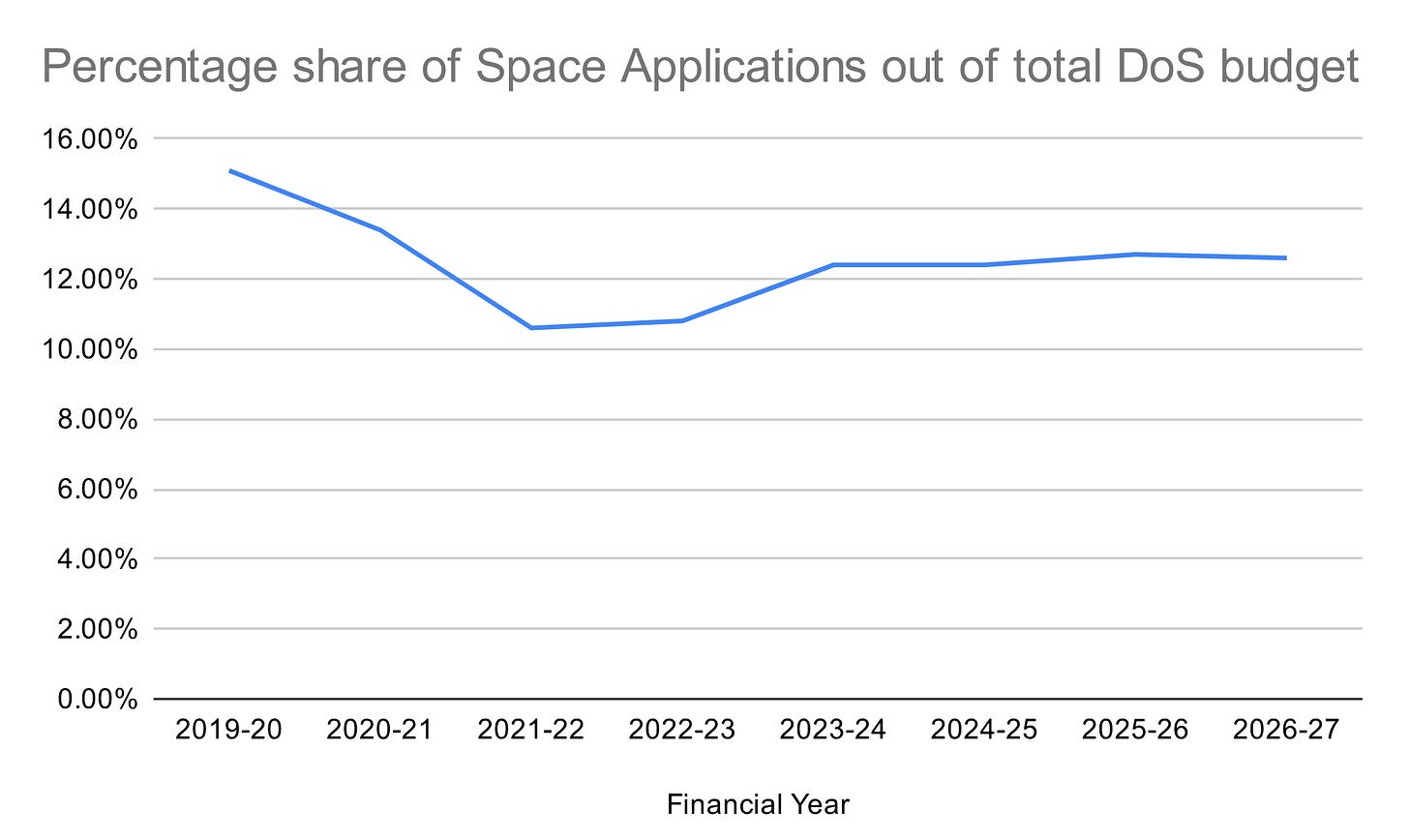

Space Technology (₹10,397 crore)

Consuming 76% of the budget, this is the bedrock of India’s space access. It covers launch vehicle development (LVM3, SSLV, NGLV), human spaceflight (Gaganyaan), and infrastructure maintenance.

Source: Past budget documents.

Despite its criticality, it sees the steepest mid-year cuts due to delays in hardware realisation.

Source: Past budget documents.

Slow pace of technology development has led the Finance Ministry to slash the budget at the revision stage for key projects. For instance, the Gaganyaan budget was cut from ₹1,200 crore (allocated) to ₹847 crore (revision) in 2024-25 due to delays in hardware realisation. The semi-cryogenic engine budget was cut from ₹190 crore to ₹115 crore. GSLV Phase-4 was cut by over ₹100 crore. So, this is a recurring pattern. The repeated mid-year cuts represent delays in crucial R&D activities. It means a slow down in indigenous innovation and delay in Indian space ambitions.

This is keeping in mind this segment’s successes that justify its high funding. The successful commercial deployment of 72 OneWeb satellites using LVM3; developing new capabilities like the SSLV to be transferred to the industry, the RLV(Re-usable Launch Vehicle) as a critical step towards reducing launch costs represent clear headway. There is the Gaganyaan progress also like the Test Vehicle (TV-D1) flight that demoed the Crew Escape System and the qualification of the LVM3 rocket for human rating.

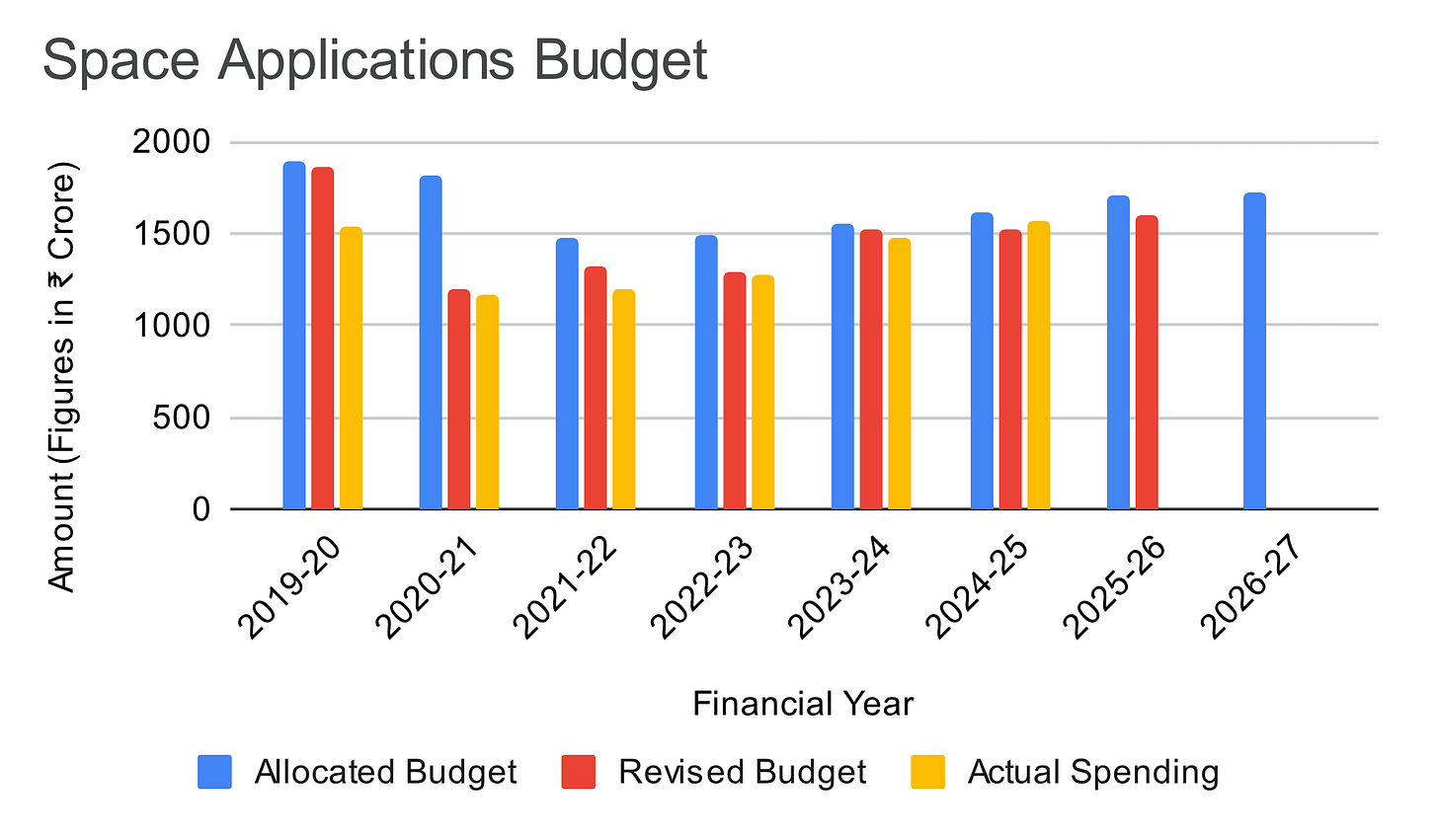

Space Applications (₹1,725 crore)

This downstream sector focuses on using satellite data for remote sensing, disaster management, and urban planning. It receives stable funding (~13% of total), primarily for day-to-day operations of centers like the NRSC and SAC.

Source: Past budget documents.

Government presumably wants the private sector to take over this part of the space operations in India. This explains the lack of growth.

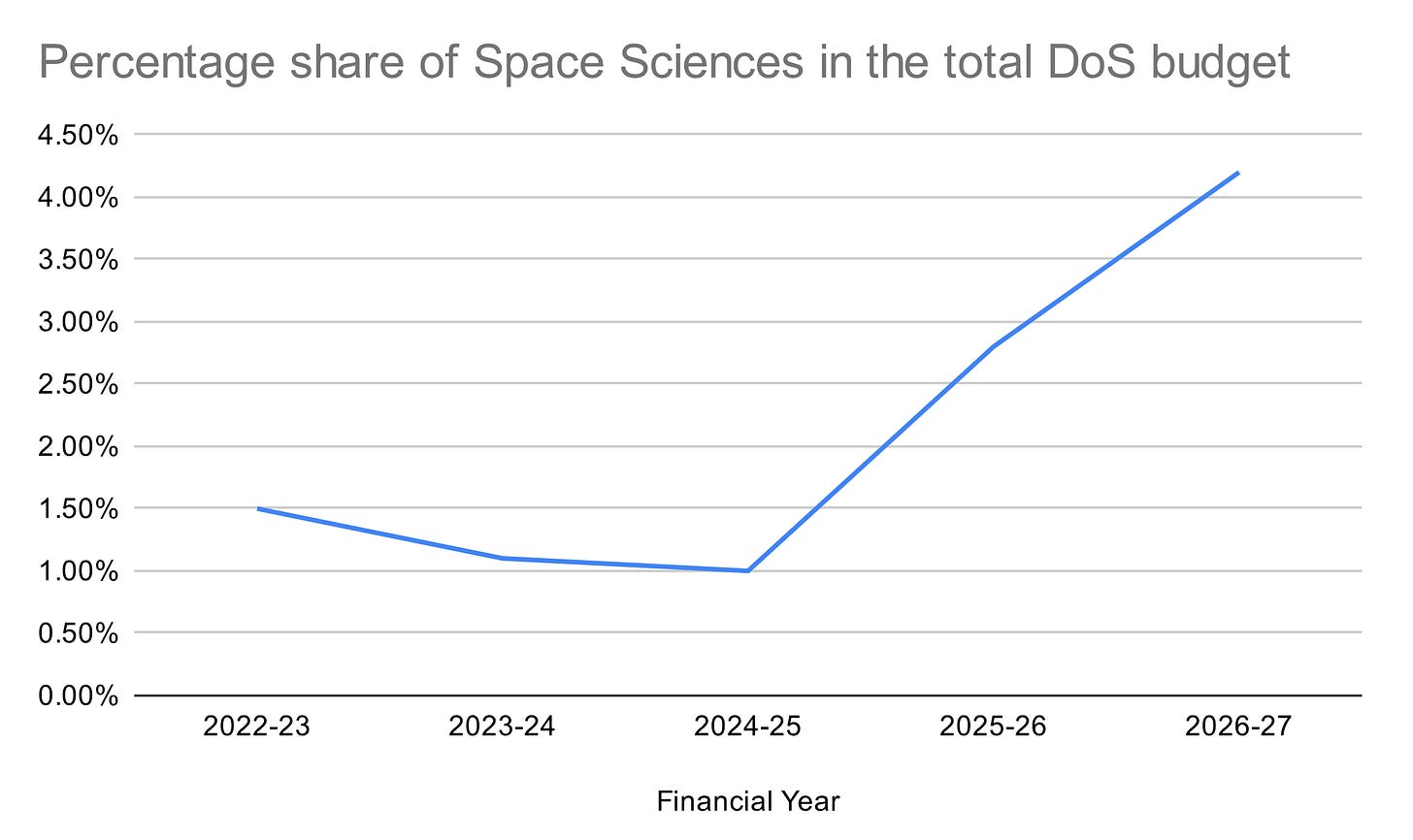

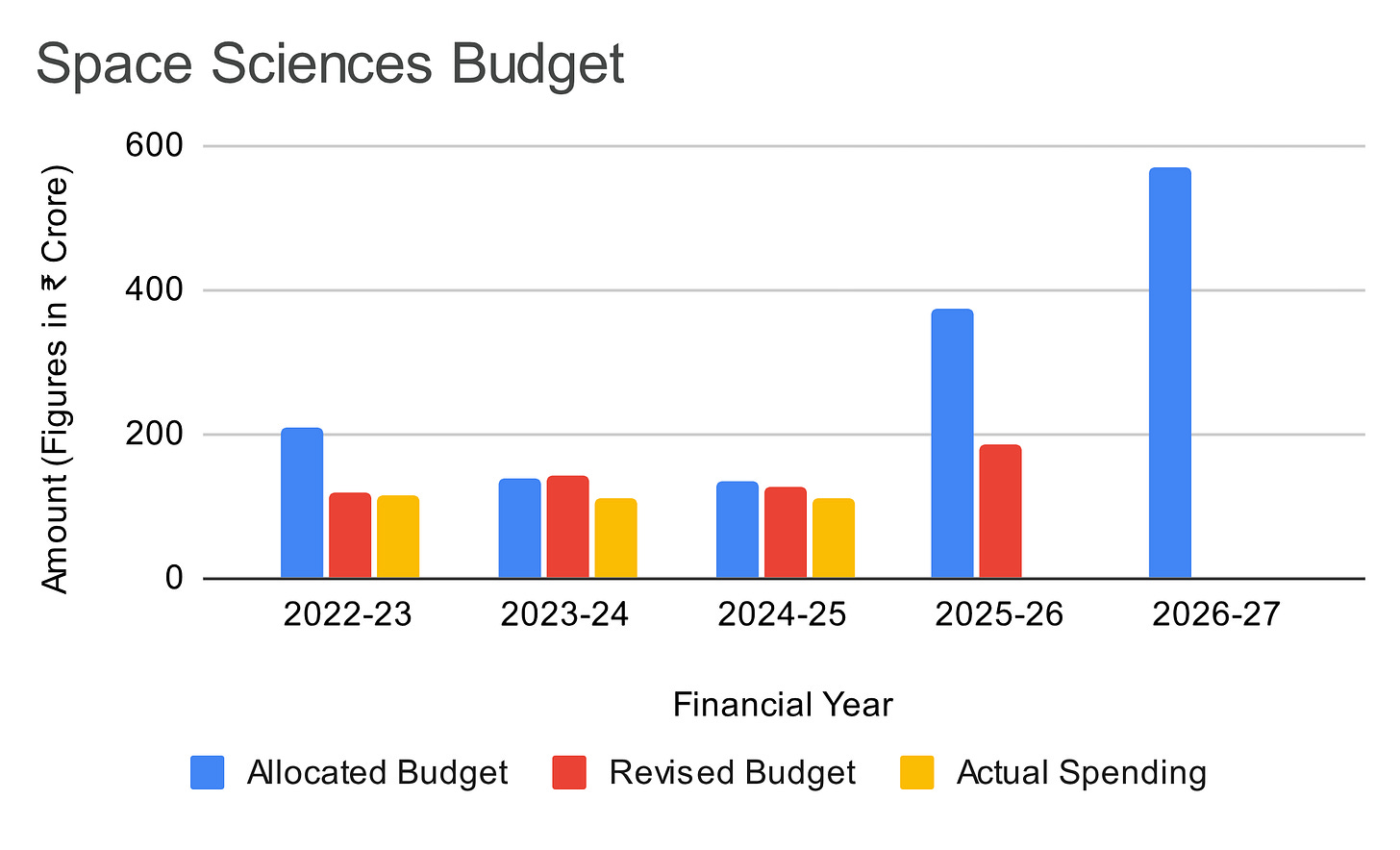

Space Sciences (₹569 crore)

This is the exploration arm funding planetary missions like Chandrayaan-4 and Shukrayaan. It is the fastest-growing vertical this year, seeing a 4x increase in funding, though it still accounts for only ~4% of the total budget.

Source: Past budget documents.

New project approvals for missions like the Chandrayaan-4 and Shukrayaan are driving the increase in budget. Chandrayaan-4 aims to bring back moon rocks. Shukrayaan will be India’s first mission to orbit Venus. There are other projects on the horizon too like the Chandrayaan-5.

Source: Past budget documents.

Space sciences is ISRO’s core mandate under the new space policy. A lot more funding and spending has to be realised here. It can only happen through a collaborative approach with ISRO involving scientists and other institutions in the country who are the primary stakeholders in these scientific endeavours.

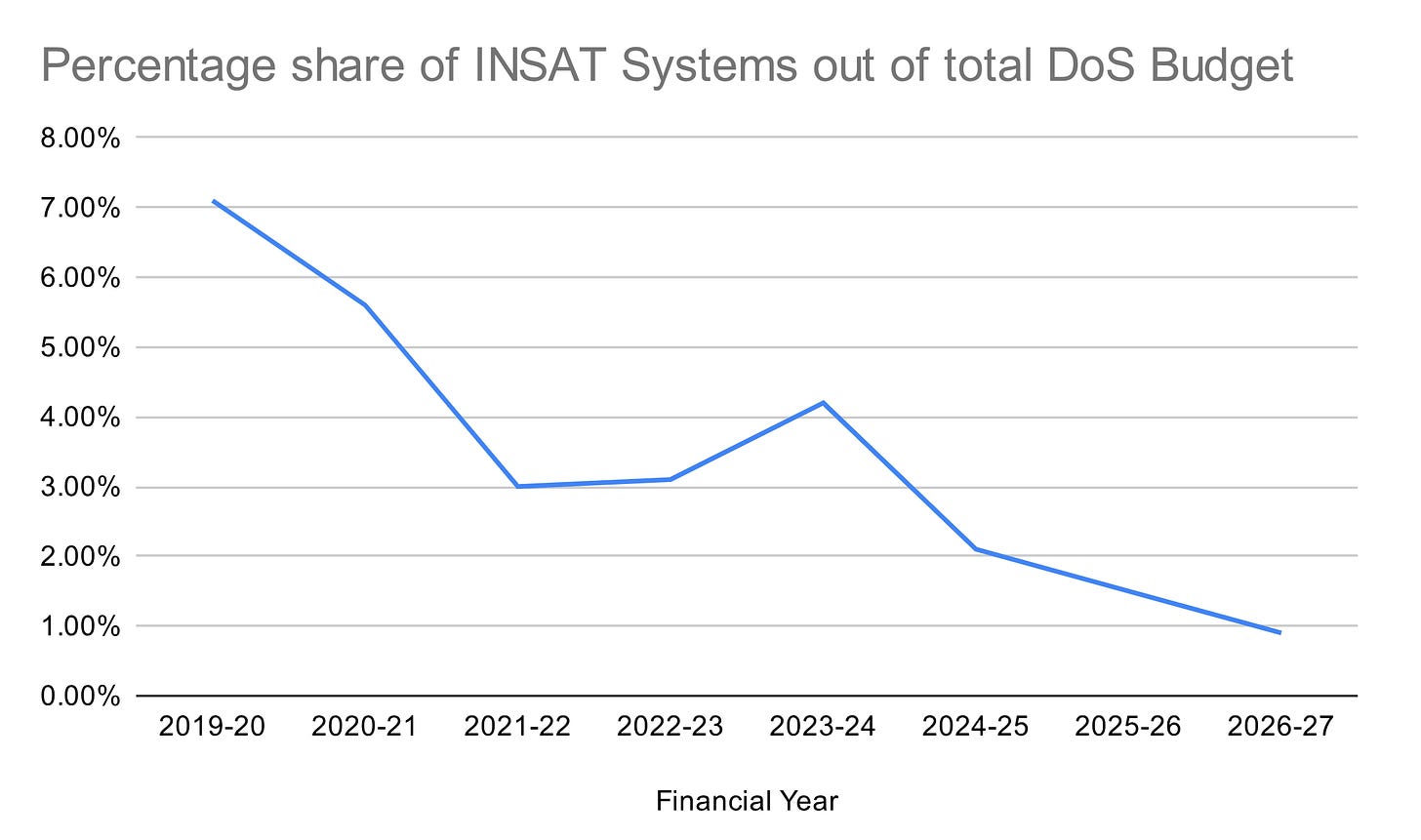

INSAT Systems (₹130 crore)

Now the smallest segment (0.9%), funding for communication satellites is being phased out of direct tax-payer support as operations transfer to the commercial arm, NewSpace India Limited (NSIL).

Source: Past budget documents.

The Capacity Bottleneck

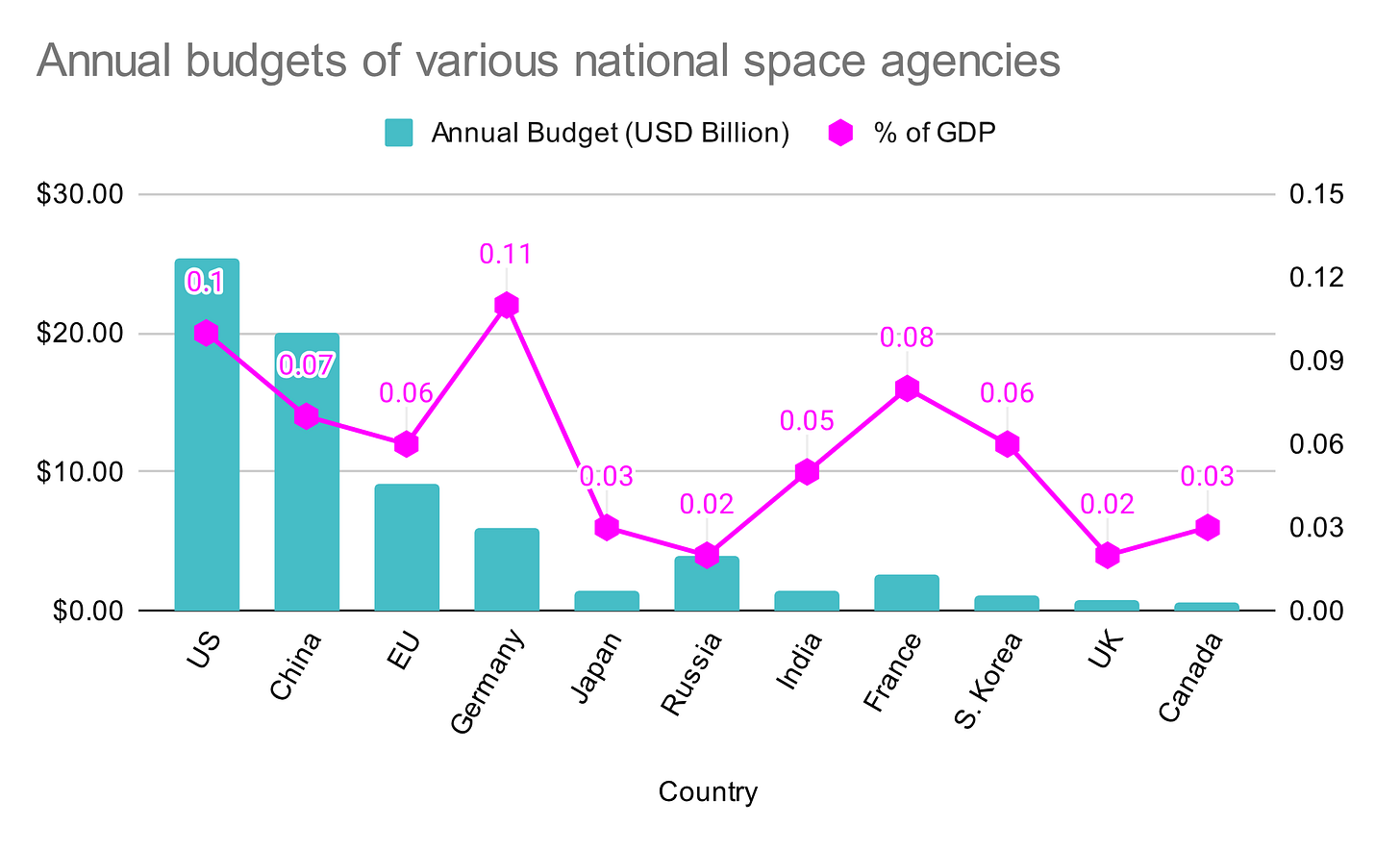

India’s space budget remains at approximately 0.05% of its GDP, which is significantly lower than other major space powers.

Source: apollo11space.

The private sector cannot do the things ISRO is tasked to perform. Planetary exploration, lunar missions, and human spaceflight aren’t just for scientific prestige. They come with geopolitical logic and are hard necessities for a space power today. Nations around the world have renewed focus and accelerated spending on their national space programs in pursuit of these goals. If India fails to keep up in these technological races, it will have to bear political costs. It will lose its seat at the table that will decide the norms, rules, and benefit sharing of humanity’s endeavours in space.

Bridging the gap between intent and outcomes

Another consistent trend we notice across all the segments and have already discussed is that the actual spending is significantly lower than allocations. Project delays are leading to unspent funds being returned. This high surrender ratio is pervasive within the broader category of scientific departments that includes space, biotechnology as well as science and technology.

This is a state capacity problem and not one of political will. The government has been consistent in allocating over ₹13,000 crores over the last few years. The political intent and support shows. The leadership wishes and expects ISRO to achieve its objectives. The bottleneck is ISRO’s absorption capacity. This is particularly evident in ISRO’s capital expenditure. A large portion of the unused budgets often comes from the capital side which includes infrastructure, equipment and facilities—all critical for long-term growth. In fact, DoS’ surrender ratio is higher compared to sectors like Defence or Road Transport which also have capital-intensive activities. Those ministries have used their capital budgets more aggressively in recent years.

This issue can be addressed by positioning the government as an anchor customer for space technology. There are over 300 startups and traditional companies in the country alongside ISRO. Most are nascent with few avenues for funding and fewer avenues for early commercialisation. There is enormous scope for the government to act as a customer through service contracts with these companies.

The anchor customer model

An anchor customer relationship is where the government commits to buying services (launch, imagery, analytics) from a private firm at meaningful scale and over multiple years. This allows the firm to justify upfront capital expenditure and attract private capital. The secret ingredient that unlocks these things is the credible demand.

This is not entirely new to the Indian experience. The first instances of government acting as a customer in the space sector began with component contracts between ISRO and industry. Vendors supplied components and subsystems to ISRO’s missions. They were build-to-print contracts. ISRO designed everything. The private sector built it according to these specifications. ISRO absorbed all the risk as well as all the credit or blame. The vendor was rewarded for delivery and not for market success. They had no incentive to innovate on architecture, business model or other downstream services.

The more recent instance of the sector moving closer to anchor customer model comes from NSIL. The space reforms have positioned NSIL as ISRO’s commercial arm. ISRO has transferred the ownership of its Earth observation and communication satellites to NSIL. Other government ministries, foreign, and domestic customers approach NSIL for space technology services. NSIL provides these services by leveraging ISRO assets and by outsourcing the work to Indian industry whenever it can. For example, the Ministry of Defence is paying ₹3,000 crores to NSIL for the GSAT-7B communication satellite to fulfil the army’s needs. NSIL will pull in the industry to build and operate the asset. Another instance is NSIL using the HAL-L&T consortium to build PSLVs. This PPP model is structurally very close to an anchor-customer model, but not quite there yet. Because the demand is still not credible enough. It is coming from outside and can be inconsistent. For instance, foreign customers may prefer to launch via SpaceX over NSIL since SpaceX offers more reliable launch schedules or cheaper costs.

In a true anchor customer model, private firms design and own the satellites, launchers, analytics platforms and offer them as services to the government. Government buys outcomes, not ownership of hardware. If the government commits to a multi-year offtake, it will have de-risked capital expenditure and the private firm will attract private equity or debt that it otherwise would not be able to. At the end of it, the firms will own their IP and can go on to export the same service globally. Many globally successful space companies like SpaceX, AWS, and Northrop Grumman emerged from this model.

India is already in the early stages of doing this systematically. There is currently an Earth observation-PPP project where a consortium of companies are investing over ₹1,200 crores to design, build, own and operate a constellation of satellites (government as an anchor customer de-risking capital expenditure). They will use this asset to sell imagery and analytics to government and armed forces in India. Though they call it a PPP, this is functionally the government acting as an anchor customer for EO services. In another instance, Telangana government has signed a contract with a private company to digitise farmlands to replace manual crop surveys. As a result, these companies have attracted new private investment (government as an anchor customer unlocking private investment).

Clearly, the anchor customer model is taking shape in the country. But the instances are few and far in between. Government should fund more contracted service payments to Indian firms that can grow and add to India’s space prowess.

This post is a condensed version of the original analysis found here: Anatomy of India’s 2026-27 Space Budget

The Post Graduate Programme in Public Policy is a comprehensive 48-week hybrid programme tailored for those aiming to delve deep into the theoretical and practical aspects of public policy. This programme emphasises both academic knowledge and hands-on experience, blending conceptual learning with policy simulation exercises. Beyond the online webinars, students also get the added advantage of engaging with Takshashila’s esteemed subject matter experts and its vast alumni community.

Overall, this intensive programme will arm you with all the essential skills for policymaking, analysis, persuasion, and communication, preparing you for your chosen career path in public policy.

And before you go-

Check out Grammar of War, a newsletter by Adya Madhavan, that looks at advanced military technologies!