Dissecting the 2024 US-India iCET Joint Factsheet

Tracking the iCET after the New Delhi Meeting

Today, Ashwin Prasad and Satya Sahu curate an analysis made by the Takshashila team as they compare the 2023 Joint Factsheet with the new one released on 17th June 2024.

If you like the newsletter, you will love to read our in-depth research and analysis at https://takshashila.org.in/high-tech-geopolitics.

On June 17, the second US-India initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET) meeting took place in New Delhi. The iCET is a collaborative framework established by the United States and India to strengthen cooperation in key technology areas. After the announcement in 2022, the inaugural meeting between top bureaucrats of both nations, chaired by the National Security Advisors, took place in 2023. The recent meeting marks this partnership's second chapter and drives it forward.

The iCET aims to bolster the two countries' economic competitiveness while complementing the innovation ecosystems. The partnership hopes to build interoperability, trust, and confidence between the two nations, which see their interests aligned across various points in recent years. It acknowledges the important role India needs to play in the Indo-Pacific and the advantage it stands to gain from the partnership with the US in this world order. This cooperation at a broader level is happening with other like-minded countries in the form of the Trilateral Technology dialogue with South Korea and QUAD cooperation with Australia and Japan.

The initiative aims to form interconnections in the two countries' industries, academia, and bureaucracies to ease barriers, expedite roadmaps, and drive collaborative innovation through funding, co-development, and co-production. The framework attempts to do this across various critical technology fields.

In this edition, the Takshashila team compares the 2023 factsheet with the new one and tracks the progress of previously announced plans and the recent expansion of the iCET framework’s scope to cover newer technology areas.

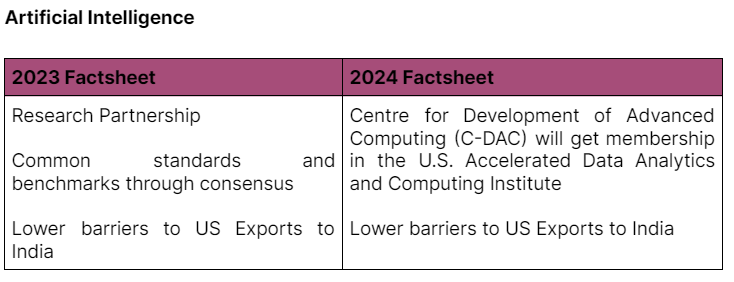

C-DAC joining the U.S Accelerated Data Analytics and Computing Institute will likely help India’s ambitions to develop extensive high-performance computing infrastructure and perhaps lead to better collaboration opportunities.

The Indian C-DAC will join other eminent institutes from the US, Switzerland, Japan, Australia, etc., to explore potential future collaborations. Each of these member institutions manages High-Performance Computing centres and supercomputers that provide key HPC capabilities to academia, government, and industry.

It is pertinent to note that the US had classified India as a “tier 3” country in its HPC export control tiers and policies in 1996. This meant that stringent export licences for HPC exports above certain computational thresholds were instituted for any entity based in India. However, in 2017, in order to implement portions of the 2016 US-India Joint Statement recognising each other as major defence partners, the US Department of Commerce amended the Export Administration Regulations (EAR) and its Validated End User (VEU) program to facilitate high-technology civilian trade between the US and VEU-eligible countries (India and China). The amendments allowed for exports to India for a wide list of military and dual-use items, but it is unclear whether HPCs are covered in this list and to what extent HPC exports to India are still restricted. Indian entities are still able to import advanced GPUs and other chips at the cutting edge to build compute clusters, and Cray supercomputers have been deployed by government departments before.

At the iCET announcement last year, the US National Security Advisor, Jake Sullivan, mentioned that “legacy technology transfer restrictions that limited India’s access…made sense in their time, but makes less sense in the year 2023”. The reiteration of this commitment to lowering barriers for US HPC exports indicates that restrictions still exist. This bodes well for India as it suggests that high-tech collaboration and cooperation in certain strategic sectors covered under the iCET can navigate complicated export control regimes like the International Traffic in Arms Regulations (ITAR).

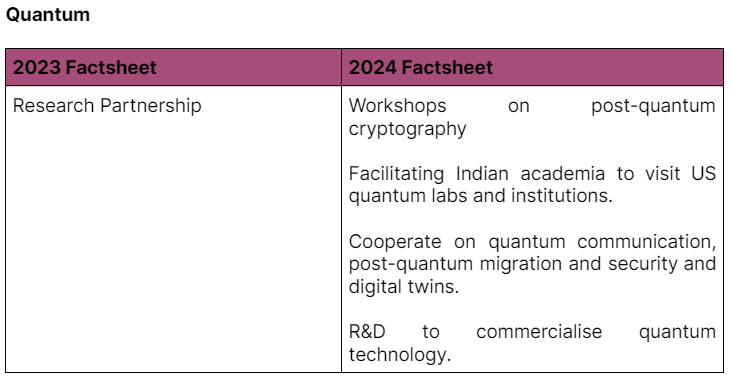

This will hopefully lead to increasing collaboration in key areas such as quantum computing and communications going forward.

The workshop on post-quantum cryptography (PQC) is the perfect place to start such a partnership. PQC will be key for both the U.S. and India in terms of managing key national security and cyber security interests, especially given China's focus on quantum technology. The increased cooperation on quantum communications and post-quantum migration also speaks to this.

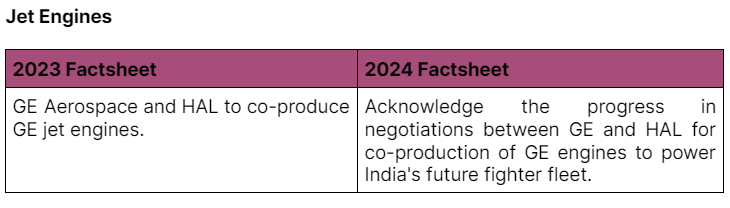

The intricacies of this complex deal matter since they will ultimately decide if there is sufficient transfer of know-how to India to lay the foundations for a domestic jet engine design and manufacturing ecosystem.

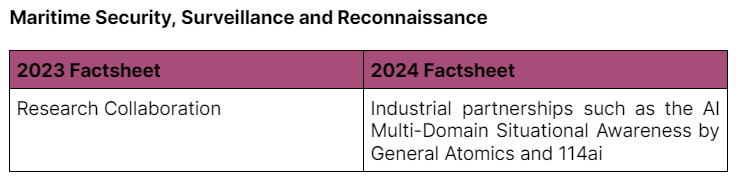

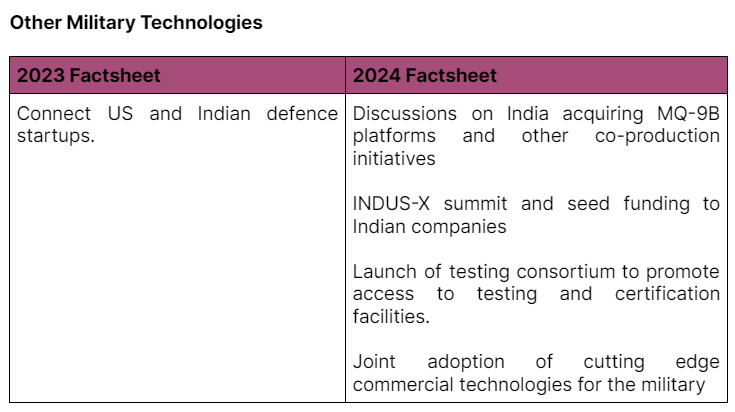

This project could potentially feed into the capabilities onboard the MQ9-Bs to be acquired by India.

The initiatives towards pooling testing and certification facilities can remove important barriers for start-ups.

INDUS-X serves as a link between entrepreneurs, investors, and government officials. Initiatives like it could also help reduce information asymmetries between start-ups and large companies.

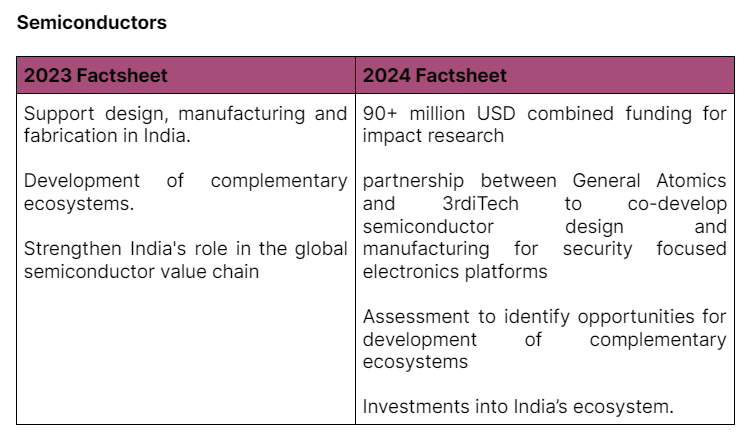

General Atomics and 3rdiTech had announced their strategic partnership in 2022, having worked closely since 2021 on co-developing semiconductor technologies. The specific partnership area was not clear at the time, so the announcement in yesterday’s statement helped greatly in that respect. It makes sense that the initial focus will be on semiconductor design since India has a sizable presence in that segment in the global semiconductor value chain.

The readiness assessment can be found here. The assessment is a largely favourable development for India since it endorses the potential for India to have a greater foothold in the global semiconductor value chain. It will go a long way to remove doubts for many US-based companies about investing in the Indian chipmaking ecosystem.

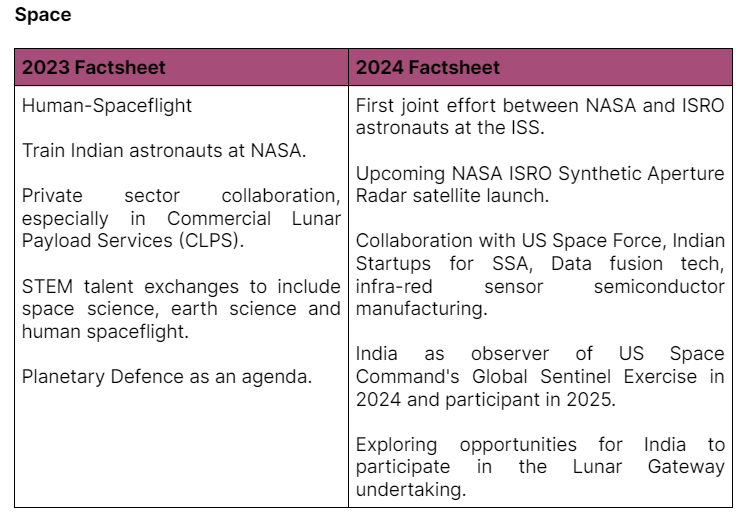

In June 2023, India and the US agreed to put an Indian on the International Space Station (ISS) in 2024.

The NISAR satellite plans to map the whole of Earth’s surface every 12 days. This kind of collaboration can yield outcomes in tracking and combating climate change. This is an example of the potential that these critical technologies hold that justifies the investment of public funds for India and warrants international collaboration.

India’s gradual inclusion in the annual multinational exercise may indicate better cooperation between the two militaries on outer space issues.

The intention to partner in CLPS and Lunar Gateway extends the objectives of the framework to the moon. CLPS is an opportunity for Indian private space firms to develop capacity in lunar operations, which has been limited so far. The Indian private space ecosystem needs anchor customers at this nascent stage, and NASA, as an anchor customer, can drive demand well.

If India chooses to participate in the Lunar Gateway, it could be a first step towards becoming a partner in the Artemis lunar exploration programme. India had signed the related Artemis Accords, a non-binding agreement on lunar governance, in June 2023.

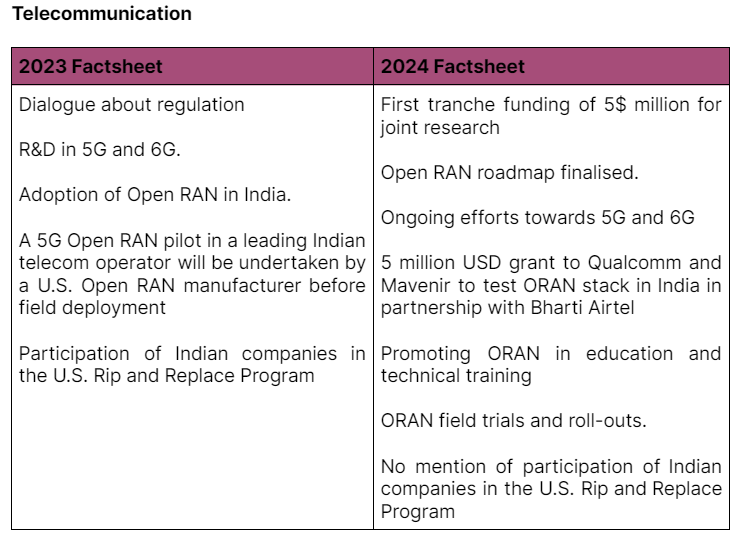

Open RAN deployments are more expensive in the near term than conventional systems and more complex to deploy. For these reasons, market trends also indicate a slow uptake. The incentives offered to deploy Open RAN compliant networks and demonstrate performance and scalability in live deployments are a great way to build confidence in the technology. Similarly, the Open RAN training and education initiatives can help build technical and regulatory capacity.

The deployments being planned seem to be single-vendor Open RAN compliant solutions by Mavenir. The complexity of multi-vendor Open RAN will be greater, and this is where the technology's benefits are realised. These deployments should also be targeted in the roadmap.

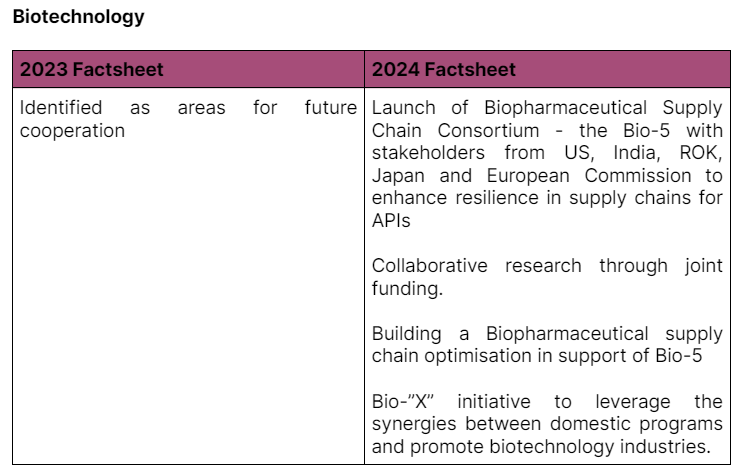

The initiative targeting supply chain resilience in biopharmaceuticals is promising and in India's national interest.

In operationalising this initiative, there is a need for investment in infrastructure for manufacturing and access to global markets for manufacturing at competitive scales and prices.

The other major policy change is the formation of Bio-X to foster biotechnology cooperation. This initiative sounds similar to INDUS-X, which was started last year for defence cooperation. However, defence cooperation is guided by a common purpose of national security. Biotechnology is a vast field with multiple goals across the agriculture, health, and energy sectors. The prevalent competition and potential areas of competition are sector-specific, and therefore, targeted interventions may be required to foster cooperation.

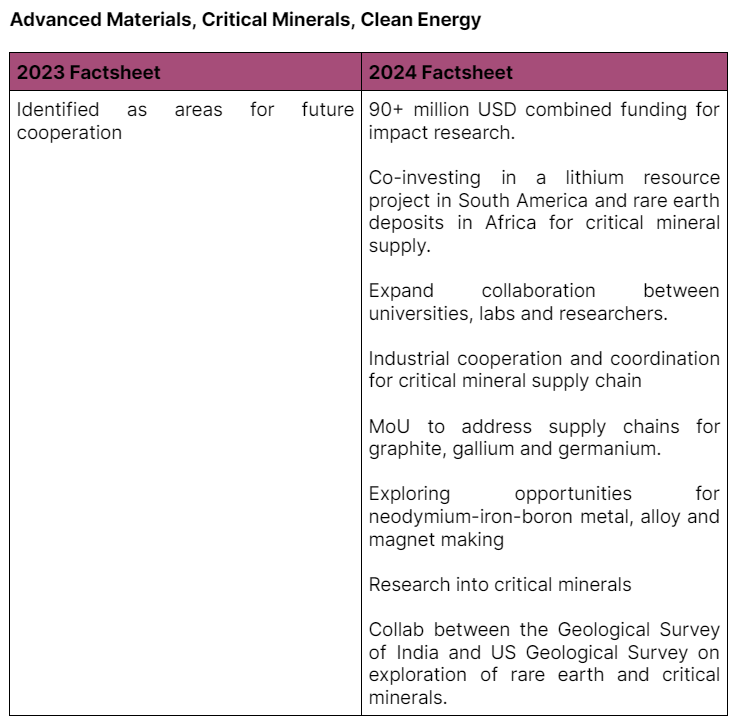

Critical minerals continue to be closely linked to clean energy transition. The US and India would like to reduce dependence on China for critical mineral supply chains.

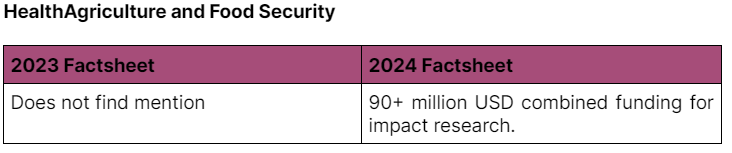

Health and food security are priority areas for India in its broader national objectives. Their inclusion into the iCET framework hints at Indian efforts to align iCET with its focus.

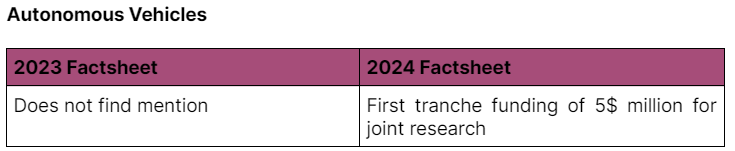

Expanding the scope to include autonomous vehicles in the framework of iCET signals the emergent nature of this technology. It is proven to be a disruptive technology that will gain market dominance in the coming years. With China’s competitive advantage in this regard, the US and Indian governments have felt the need to build capacity in this area.

The effectiveness of the iCET initiative ultimately rests on the successful implementation of the plans and collaborations outlined. By addressing challenges and maintaining a commitment to the partnership, both countries can maximise the potential of iCET and realise the intended benefits for their respective technological, economic and geopolitical landscapes.

This analysis was a joint effort from the Takshashila team.

Aditya Ramanathan has written about India and Artemis Accords here.

Satya Sahu was in conversation with the Information Technology and Innovation Foundation’s Stephen Ezell (who authored the aforementioned readiness assessment) on a podcast to discuss these findings.

Bharath Reddy's analyses of the challenges and pathways for Open RAN adoption can be accessed here and here.

Shambhavi Naik’s recommendations for Bioeconomy can be found here.