#68 Model Misconduct: The NYT's Challenge to OpenAI's License to Learn

On the Rights of Writers - NYT vs OpenAI, Cosmic Courtesy and Friendly Restraint - India’s Lunar Diplomacy

Today, Rijesh Panicker highlights the tough task before the court in NYT vs OpenAI, as it decides a case pivotal to the future of Generative AI’s impact on Intellectual Property Rights.

Aditya Ramanathan then prescribes a possible path forward for India to advocate for its lunar ambitions diplomatically on a stage dominated by the US and China.

Also,

We are hiring! If you are passionate about working on emerging areas of contention at the intersection of technology and international relations, check out the Staff Research Analyst position with Takshashila’s High-Tech Geopolitics programme here.

CyberPolitik: On the Rights of Writers - NYT vs OpenAI

— Rijesh Panicker

Generative AI faces a copyright conundrum.

In a detailed rebuttal against The New York Times's lawsuit, Open AI points out that the examples showing plagiarism by the NYT require extensively formatted prompts that effectively call on the model to search and retrieve the exact document, that "regurgitation" - which they define as the exact or close to the exact reproduction of training documents is a rare bug that is being driven down to zero over time. They also state their belief that the use of copyrighted material for AI training is fair use, and they are actively collaborating with partners like Springer and Associated Press to license data,

OpenAI does have a point about the examples submitted by the New York Times. The examples provided in the document clearly use very detailed prompts, often long stretches of text from the original article, to get a response from ChatGPT that looks like plagiarised content. One could make the case that the average user seeking responses from chatGPT based on simple prompts or small sets of sentences is unlikely to get plagiarized content. OpenAI's notion of "regurgitation" is based on this exact idea - that the average user is unlikely to generate copyright-violating material and that guardrails can be retrospectively created to bring this rate down to zero.

However, the New York Times lawsuit is based on the claim that Open AI has used a very large number of its articles as part of the training process for GPT-4 thus violating copyright. Further, In a submission before the House of Lords Communications and Digital Select Committee into Large Language Models, Open AI has admitted that it is impossible to train AI models today without accessing copyrighted material due to the pervasive nature of copyrighted content. They further claim that models made only using public domain information, limiting them to very old textual data, would be useless today.

This problem is not restricted just to chatGPT. In an interesting review for the IEEE Spectrum, Gary Marcus and Reid Southen have showcased how AI models like MidJourney and DALL-E generate images that violate copyright with simple, generic prompts. As our digital tools continue to integrate these AI models, the risk of end users inadvertently infringing copyright increases significantly. The simplest solution involves retraining large AI models with appropriately licensed or only open-domain data. The second is to try and build guardrails around trained models that prevent violations. As the IEEE article documents, guardrails are easy enough to break with most models.

Ultimately, courts will need to decide if the training of large AI models on copyrighted material falls under the "fair use" doctrine. If, indeed, LLMs and other large AI models are capable of generalizing from information and creating original ideas, there is a case to be made that the gains to society are so large that copyright protection should be diluted. As a recent example, courts have ruled that Google's digitisation of copyrighted books constituted fair use.

In the long run, either outcome creates its own set of problems. Should the New York Times win, we could see a situation where data creators end up imposing high licensing costs on AI model developers, driving consolidation in favour of large, well-funded firms. In such a scenario, we should expect that models from OpenAI, Google, etc, will dominate. If Open AI wins, we could end up creating a long-term disincentive for the creation and propagation of original content, ultimately destroying the quality of content and ideas being generated, both by humans and machines.

India is set to host the Quad Leaders' Summit in 2024. Subscribe to Takshashila's Quad Bulletin, a fortnightly newsletter that tracks the Quad's activities through the Indo-Pacific.

Your weekly dose of All Things China, with an upcoming particular focus on Chinese discourses on defence, foreign policy, tech, and India, awaits you in the Eye on China newsletter!

The Takshashila Geospatial Bulletin is a monthly dispatch of Geospatial insights for India’s strategic affairs. Subscribe now!

Antariksh Matters: Cosmic Courtesy and Friendly Restraint - India’s Lunar Diplomacy

— Aditya Ramanathan

India’s landmark decision to sign the Artemis Accords in June 2023 surprised seasoned observers who have been critical of the US-led initiative. The Artemis Accords are a set of non-binding guidelines for human activity on the Moon. Detractors, including Russia and China, see the accords as an attempt to build a new set of customary space laws that favour US interests. Nevertheless, as of December 2023, a total of 33 states had signed the Artemis Accords.

India’s signature is best understood as a high-level political decision that may have involved quid pro quos with the US. Nevertheless, India’s choice makes two things clear. One, India sees other Artemis signatories as its most important partners for space exploration rather than its traditional collaborator, Russia. Two, India sees few downsides in signing the Artemis Accords since it considers the immediate prospects for a new multilateral lunar treaty to be poor.

Indi was a signatory to the Moon Treaty, which came into effect in 1984. That treaty failed to impress any major spacefaring states, which saw it as overly restrictive and forced them to share the fruits of lunar exploration with less developed states. Presently, the Moon Treaty has only 17 ratified state parties and four other signatories. Yet, as a fledgling spacefarer in the 1970s, it was in India’s interest to join an effort to constrain the actions of more advanced states that were looking to the Moon.

Much has changed over the past half-century. India’s successful Chandrayaan-3 mission was followed just months later by the announcement that it planned to land one of its nationals on the Moon by 2040. As a middling spacefarer, India will have to adopt a more calibrated approach than when it helped negotiate the Moon Treaty. However, since India is likely to achieve its lunar goals later than the US and China, its primary goals will be to:

1. Retain freedom of action for its own ambitions, including uncrewed and crewed lunar exploration and resource extraction.

2. Place reasonable restraints on leading spacefarers to ensure a conducive environment for the newcomers to lunar exploration.

How India achieves these goals will depend on the evolution of US and Chinese lunar capabilities.

Navigating a Path Towards Lunar Governance

There are four potential scenarios for US and Chinese lunar capabilities:

Neither the US nor China make much progress in lunar exploration.

US capabilities evolve faster than Chinese.

Chinese capabilities evolve faster than those of the US.

Both US and Chinese capabilities evolve rapidly.

Scenarios for Lunar Governance 2024 - 2045

In the figure above, we see that mutually weak capabilities result in weak governance since there are few incentives to create a new legal architecture for the Moon. On the other hand, major disparities in capabilities lead to contested governance, making it harder to reach a widely accepted agreement. Finally, when the capabilities of both the US and China are strong, there is a greater incentive to accept mutual restraints. While it is far from certain that strong capabilities will result in strong governance, it is the scenario in which such an outcome is most likely.

Two of the four scenarios mentioned can be dismissed as low probability: mutually weak capabilities and China gaining a lead over the US in the next two decades. That leaves us with either (1) strong US-China competition for lunar exploration, creating the potential for strong governance or (2) a US lead in lunar exploration, creating the potential for contested governance.

In both these scenarios, India must adopt a strategy of ‘friendly restraint’, meant primarily to ensure that the US is encouraged to act responsibly. To create conditions for friendly restraint to work, India must do the following:

Publicly acknowledge India’s preference for a new, widely accepted, legally binding multilateral lunar governance treaty.

Support the creation of a consultative mechanism among Artemis signatories to enable open discussion on key issues such as deconfliction, heritage sites, and resource utilisation.

Support the creation of new working groups under the UN’s Committee for the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space to create concrete proposals on lunar governance. It is proposals such as these that stand some chance of eventually becoming part of a new, widely accepted lunar treaty.

Ultimately, lunar governance will be about more than a new treaty. It will require norms, guidelines, and best practices to supplement a formal legal architecture. India needs to begin pushing for it now.

Bengaluru Event Alert!

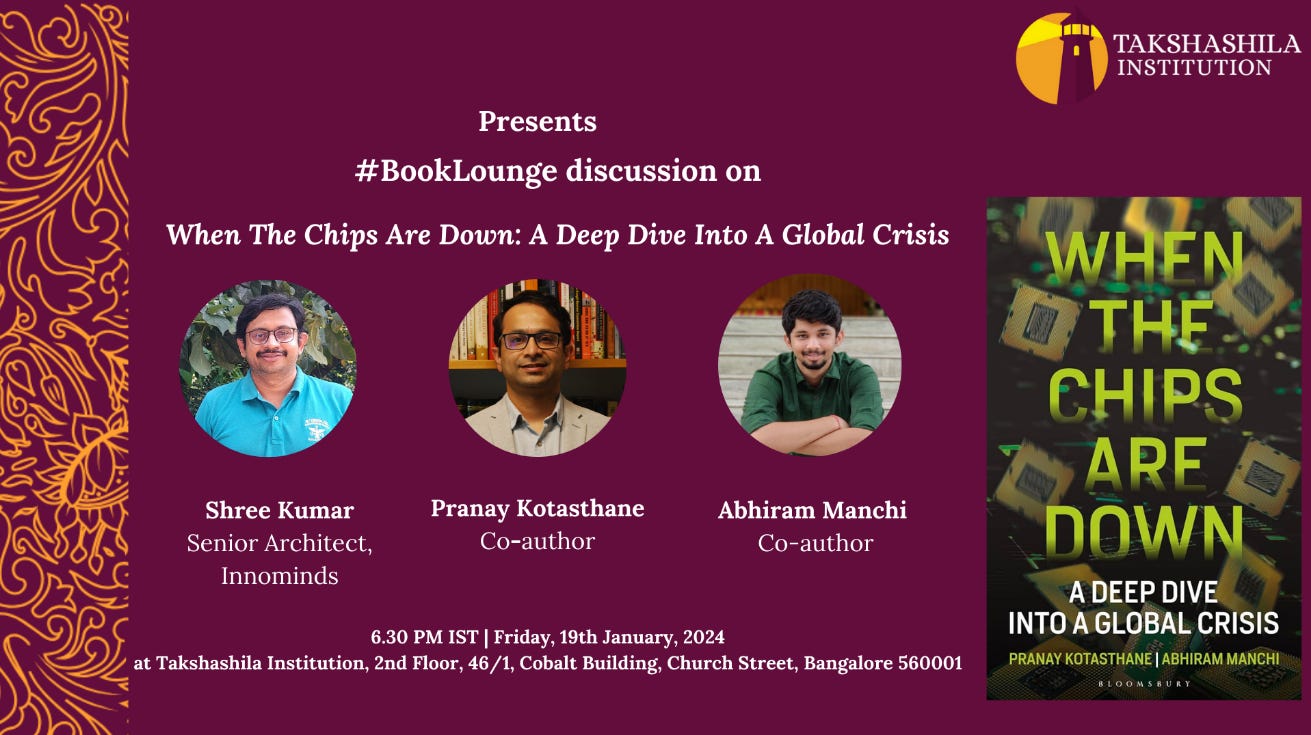

Takshashila presents #BookLounge discussion on the latest hit, “When The Chips Are Down: A Deep Dive Into A Global Crisis”, authored by Pranay Kotasthane and Abhiram Manchi.

Shree Kumar, Senior Architect, Innominds, will host the conversation.

Click here to read more about the book and here to purchase a copy. The event is open to all. You can find our location here.

RSVP at contact@takshashila.org.in

What We're Reading (or Listening to)

[Podcast: All Things Policy] Siliconpolitik: Making Imaging Sensors for Space Telescopes ft. Vish Madhugiri

[Book] Party of One: The Rise of Xi Jinping and China's Superpower Future, by Chun Han Wong

[Opinion] Poonch incident should encourage military justice review. Bring one law for three Services, by Lt.Gen. Prakash Menon

[Opinion] Analysis: Trump and the art of electoral endurance, by Sachin Kalbag

Copyright issues of writings have been an issue for long.

These require understanding& education of info process. Publishing, writing, peoples ability in expressions& intersection of market/ politics/weaponized/activism issues. World is filled with different governance models ranging from lack of freedom in speech/communication, feudal dictatorships, military to democracy with freedom. But internet access is there for all. How does it translate?