#53 Strategic Partnerships sans Dependence, Generative AI Censorship, and Financial Advice for American VC firms.

India-US Partnership in Advanced Telecoms, Defining Dependence-induced Vulnerabilities in Asymmetric Trade Interdependence, American Venture Capitalists, where is your money going?, Censoring AI LLMs

If you would like to contribute to TechnoPolitik, please reach out to satya@takshashila.org.in

Course Advertisement: Admissions for the Sept 2023 cohort of Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Public Policy (Technology and Policy) programme are now open! Visit this link to apply.

Cyberpolitik Explainer : India-US Partnership in Advanced Telecoms

— Bharath Reddy

The telecom sector holds significant strategic importance and has been recognised as a critical sector within the framework of the Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET) initiative by India and the U.S. In a market dominated by a handful of Chinese, European and South Korean companies, India and the U.S. have common interests and can leverage their complementary strengths to achieve them.

During prime minister Modi's visit to the U.S., the broad areas identified for collaboration are:

Research and development on advanced telecom technologies.

Increasing adoption of O-RAN (Open Radio Access Network) to achieve economies of scale.

Welcoming participation of Indian companies in the Secure and Trusted Communications Networks Reimbursement Program, a.k.a. the Rip and Replace Programme.

Let's unpack each of these.

Research and Development (R&D) on Advanced Telecom Technologies

Chinese companies have contributed slightly over a third of the total standards contributions towards 5G. Huawei and ZTE have invested heavily in R&D and have an even bigger lead in 6G development which should start deploying by 2030. Concerns around Huawei's ownership structure and Chinese laws that require companies to assist in national intelligence work raise red flags. These concerns have led many countries, including the U.S. and India, to keep Chinese companies out of their 5G networks.

5G and, to a greater extent, 6G expand communication network capabilities and use cases. With Chinese companies increasingly shaping the standards for these technologies, concerns exist about whether they might be designed to allow greater state surveillance. Broader participation in standards development by diverse stakeholders could address such concerns. Additionally, it will provide an opportunity to accommodate use cases that tackle conditions unique to specific regions that may otherwise be overlooked or unrepresented.

In this context, efforts are ongoing worldwide to ramp up 6G research and development. Hexa-X is a joint European initiative to shape 6G, Next-G is an initiative to advance North American wireless technology leadership, and the recently announced Bharat-6G aims to do the same for India. Although a common standard would be ideal for interoperability and economies of scale, geopolitical considerations might result in a different outcome. We could end up with two diverging paths for 6G standards - one led by the U.S. and Europe and the other by China.

Building Economies of Scale for O-RAN

The telecom equipment industry has high entry barriers and is dominated by a handful of vendors. The top five vendors that account for most of the market are Huawei, Ericsson, Nokia, ZTE, and Samsung. Bans imposed against Huawei and ZTE further limit vendor choice. The lack of competition in the market could lead to a decline in innovation, an increase in prices and the risk of disrupted supply chains.

The companies with the largest RAN market share are full-stack vendors offering tightly integrated solutions. Open RAN promises to reduce entry barriers by disaggregating the RAN ecosystem. This allows smaller vendors to enter the market by building interoperable and modular components. These modular components could then be integrated like Lego blocks to create end-to-end solutions.

However, this comes with the risk of complexities in system integration. The responsibility of a reliable and secure system will shift from a single vendor to system integrators and regulators. This complexity and low maturity levels of O-RAN solutions have delayed their adoption by Indian operators during the recently announced 5G deals. However, financing support from the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and USAID, under the iCET, could give the impetus for the broader adoption of O-RAN.

Participation of Indian Companies in the Rip and Replace Programme

This Programme which took effect in 2020, mandates American companies to remove, replace, and dispose of communications equipment and services that pose a national security risk. These are based on concerns by U.S. agencies that Chinese gear could be used for espionage and to steal commercial secrets.

Much like ripping off a band-aid, the Rip and Replace Programme has been painful for some. The costs have already exceeded $5 billion, more than double the $1.9 billion budgeted under the Programme. It also disproportionately affects smaller operators more likely to have low-cost Chinese equipment. The move welcoming Indian companies as "trusted sources" for telecom equipment can be a win-win for India and the U.S. It provides cost-effective options for U.S. operators and opens new opportunities for Indian telecom equipment vendors.

The United States and India share common interests in how technology is designed, developed, governed, and used. In the current environment that sees technology increasingly enmeshed with geopolitics, these initiatives should strengthen the innovation ecosystem and build resilience in the supply chains for both countries.

Matsyanyaaya 1 : Defining Dependence-induced Vulnerabilities in Asymmetric Trade Interdependence - A Conceptual Framework

— Amit Kumar

** This article stems from a Takshashila Discussion Document accessible here.

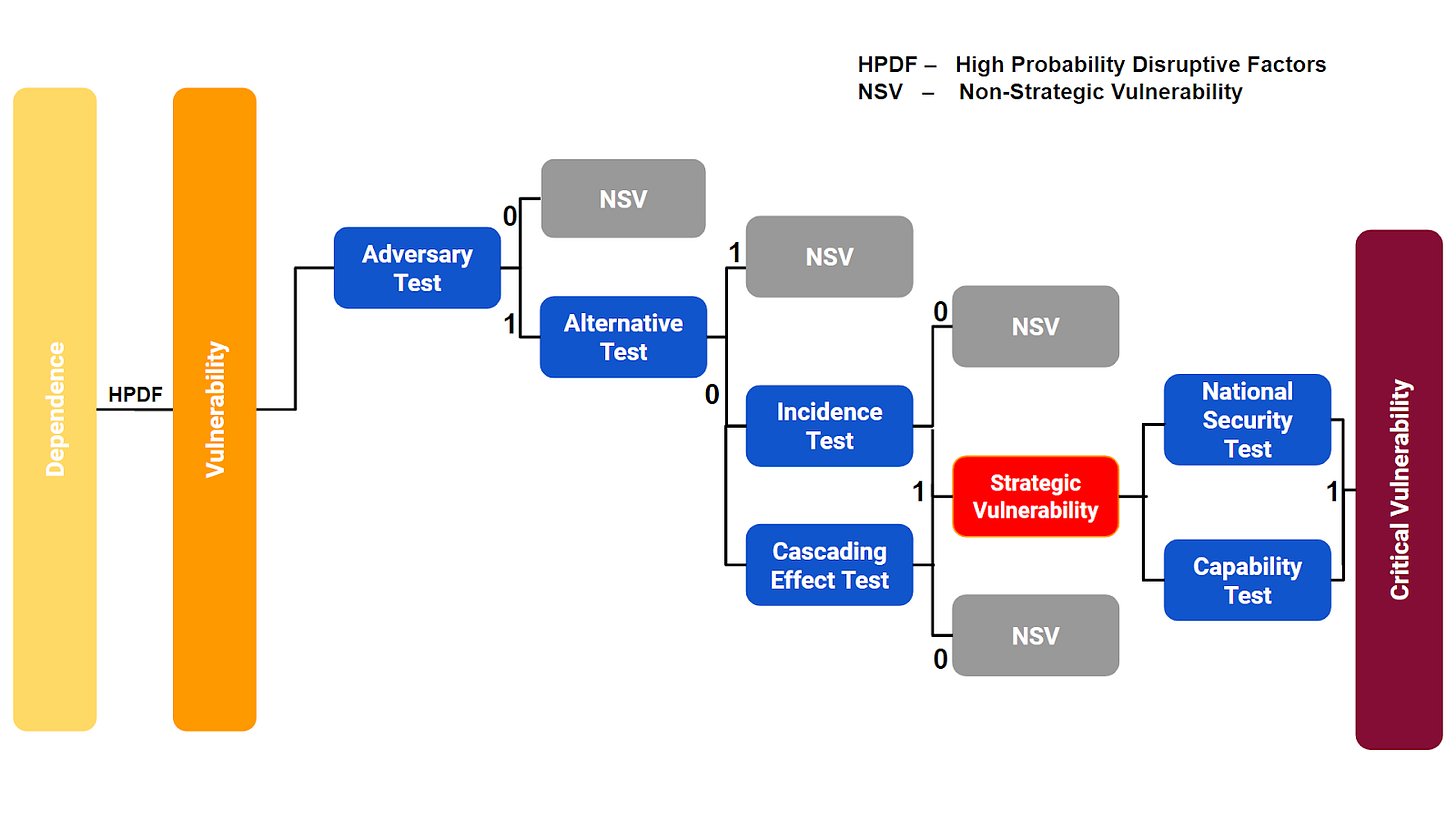

As the world becomes more economically integrated, a complex web of asymmetric interdependences has emerged, allowing some states to wield disproportionate economic power. Consequently, recourse to economic coercion as a tool for compliance, deterrence or co-optation has become much more frequent. Debates around dependence-induced strategic and critical vulnerabilities have thus gained traction with an end objective to reduce or mitigate them. But a lack of conceptual framework underpinning the ideas of dependence, vulnerabilities, and strategic and critical vulnerabilities plagues the present decision-making apparatus, which runs the risk of treating subjects under each category as synonymous. To prevent a one-size-fits-all approach emanating from the lack of conceptual differentiation, this paper presents a framework through a series of tests to understand whether trade in a specific commodity between countries can be classified as a critical vulnerability.

The following flowchart depicts the recommended framework, which passes every case of dependency in an asymmetric trade relationship through a series of tests to identify whether it constitutes a strategic vulnerability, critical vulnerability, or a simple case of dependence/non-strategic vulnerability.

This paper forms the first of a series of outputs on dependency-induced vulnerability in international trade. It shall ultimately serve as the backdrop for future outputs in this series. The framework discussed in this paper will subsequently be applied to various case studies globally, with the central study of interest being the India-China trade relationship.

Read the full paper here.

Matsyanyaaya 2 : American Venture Capitalists, where is your money going?

— Anushka Saxena

On July 19, 2023, the US government House Select Committee on the Strategic Competition Between the United States and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) announced that it had sent letters to four American companies – GGV Capital, GSR Ventures, Qualcomm Ventures, and Walden International – seeking information about their venture capital investments in Chinese entities working on critical technologies such as Artificial Intelligence and Semiconductors. Following are the primary concerns that emerged from the letters drafted by Committee Chairman Mike Gallagher (R-WI) and Ranking Member Raja Krishnamoorthi (D-IL):

American businesses should be wary of how they spend their money, especially when investing in Chinese projects and entities. Because of the authoritarian nature of the Chinese party-state, no company is “truly private”. In this regard, how any venture capital put into Chinese entities is utilised depends on the CCP.

Because the CCP has a history of using AI surveillance networks in collaboration with Chinese tech firms like Intellifusion to violate human rights in the Xinjiang province’s Uyghur Autonomous Region, any investment flowing into such firms from American venture capitalists may lead to the latter becoming a party to the CCP’s human rights abuses. Walden is investing in Intellifusion and other Chinese firms working on AI and semiconductors (such as Biren Technology).

China adopts a civil-military fusion (军民融合) strategy, which essentially blurs the line between research, equipment and facility undertaken/utilised for civilian purposes and deployed in a dual-use manner for military purposes. In the letter, Qualcomm Ventures, which is investing in the China-based firm ‘Zongmu’, specifically in its self-driving vehicles project, was reminded that Zongmu operates out of an industrial park that lists ‘military-civilian integration’ as one of its primary objectives.

Subsequently, the four American firms were required to respond to some questions of national importance by August 1, 2023. These questions broadly include information about dollar-by-dollar investments made to the Chinese entity of concern and if any funding was received in return; the due-diligence process followed by the VC firms; and whether they have any mitigation strategy in place in case the US Commerce Department places the investee firms under sanctions through its ‘Entity List’.

This move by the Select Committee indicates that the US-China contestation threatens sanctions against Chinese firms to cause a course correction in how American businesses function vis-a-vis China and create a threat of sanctions against Chinese firms listed in the letters, to coerce some political outcome.

The US Government is increasingly attempting to force an alignment between national security interests and business interests. This is also evident from the purpose of the CHIPS and Science Act, which has prevented firms like Intel from opening up a new semiconductor fab in China, and instead looking inward to expand its US operations.

These letters are the next stage in a slew of precedent-setting decisions by the US Congress, which indicates a bi-partisan consensus on looking at China from a strictly rivalrous perspective and having American businesses operate from that perspective.

Cyberpolitik Explainer : Why Censoring Generative AI and Large Language Models Is So Hard

— Satya S. Sahu

It’s not difficult to find evidence that Generative AI and Large Language Models (LLMs) pose many ethical and social challenges, such as generating misinformation, fake content, or harmful content. Recently, I was part of the evaluation process for the introductory policy workshop undertaken by the current cohort of Takshashila’s Graduate Certificate in Technology Policy. (Apply here for Sep 2023 intake!) The topic was broadly on AI regulation and governance in the Indian context. A common thread that emerged in almost all the student groups tackling this difficult policy question throughout the exercise was a focus on combating AI-generated misinformation. While policy measures ranging from the now commonly iterated requirement for disclosure of training datasets to more innovative ones involving watermarking of AI-generated content were discussed, it was striking (in a good way!) how censorship of content (an approach that should be familiar to anyone who has studied the way the Indian state has traditionally sought to control mass media) was not discussed. But why is this the case - even when seasoned AI governance experts meditate on ways to stem the flow of AI-generated misinformation? How can we censor these technologies to prevent or mitigate their negative impacts?

Censoring generative AI and LLMs is a challenging task for one. First, there is no clear definition or consensus on censorable content. Stakeholders may have different views and values on what is acceptable or unacceptable, depending on their cultural, political, or moral backgrounds. For example, some may consider certain topics or expressions offensive, sensitive, or taboo, while others may not. (this takes on more significant proportions as societal elements become more polarised) Some may advocate for free speech and creativity, while others may prioritise safety and security.

This creates a dilemma of balancing the competing interests and rights of various parties involved in producing and consuming generative content. Censorship in a legal context will also mean having constitutionally-compliant laws that define what is problematic enough to be censored by a body legally empowered to do so, with an entire concomitant process for appeals and the like. It is substantially costly, time-consuming, and, as mentioned, consensus is difficult to concretise in law.

One possible solution is to adopt a human-centric approach to censoring generative AI and LLMs. This means that the principles of human dignity, autonomy, justice, and welfare should guide censorship decisions. Moreover, the censorship process should involve human oversight, participation, and feedback. For instance, human moderators could review the generated content and flag or remove any inappropriate or harmful content. Alternatively, human users could rate or report the generated content and provide feedback to improve the quality and reliability of the generative AI and LLMs.

Second, no simple or universal way to detect or filter censorable content exists. Generative AI and LLMs are complex systems that can produce diverse and unpredictable outputs. They can also adapt and learn from new data and feedback, making them harder to monitor or control. Moreover, they can generate content that is realistic, fluent, and coherent but also nonsensical, biased, or misleading. This can make it difficult to distinguish between fact and fiction or between genuine and malicious intent. What is the characteristic censorable difference between Google Pixel’s AI-driven algorithms that allow you to cut out distracting elements in that perfect vacation photo and an AI-driven tool used to cut out a crucial contextual element in an image in a fake news article circulated on social media?

Another possible solution is to adopt a transparent and explainable approach to censoring generative AI and LLMs; these could provide explanations or justifications for the generated content, such as the reasoning behind the content, the assumptions made by the model, or the limitations of the model.

Further, censoring these technologies may require significant human and computational resources and legal and ethical frameworks that may not work well across multiple jurisdictions. These resources and frameworks may not be available or adequate in all contexts or domains. For example, some countries may have more stringent or lax laws and norms on censorship than others. Some jurisdictions may have more clear or vague standards and guidelines on censorship than others. Furthermore, censoring these technologies may have unintended or undesirable consequences, such as violating the privacy of users who use the LLM, infringing on the intellectual property of the entity owning the LLM (or maybe, if it comes to pass, the user who generated the content using the LLM!), and limiting innovation etc.

Finally, censorship decisions should be aligned with the best practices and benchmarks in the field, constantly subject to evaluation and audit. For instance, generative AI and LLMs could be tested and validated against various metrics and datasets, such as accuracy, fairness, toxicity, or diversity. Alternatively, independent and qualified authorities, such as regulators, auditors, or ethics committees, could monitor and review generative AI and LLMs. As the adoption of generative AI and LLMs increases exponentially, a correlated increase of independent monitoring personnel is perhaps not even feasible. Further, questions arise about who maintains this intricate system- the state, an independent regulator, or even self-regulating private industry.

These challenges are particularly relevant for India, among the world’s largest data markets and one of the most diverse and complex societies. India is already battling a flood of misinformation worsened by the multiplicity of Indic languages. Generative AI technologies can further accentuate the problem by creating fake content in various languages that can influence public opinion or incite violence. Moreover, India has a rapidly evolving legal and regulatory landscape for digital platforms that pose uncertainties and challenges for censoring generative AI technologies. Sometimes, this environment can enforce censorship of AI-generated content by virtue of providing for an extreme amount of overbreadth in its laws. For instance, India has recently introduced the IT (Intermediary Guidelines and Digital Media Ethics Code) Amendment Rules, 2023. The Rules require social media intermediaries to censor or modify content related to the Union government if a government-mandated fact-checking unit directs them to do so. However, these rules may not be sufficient or adequate to deal with the scale and complexity of generative AI technologies, as we continue to run into the same problems outlined above, only now with negative marks awarded to the country’s plummeting free-speech index.

Therefore, censoring generative AI and LLMs needs to balance the benefits and risks of these technologies and the rights and responsibilities of their providers and users. We need to develop and apply ethical principles and standards for designing and using these technologies, such as human-centricity, transparency, privacy, security, inclusivity, and accountability. All these are factors that are already difficult to incorporate into the training and development of generative AI and LLMs, so censoring the content is a challenge that a) may not address the root causes of increasing misinformation and b) is understandably going to find fewer takers at this time.

What’s on our Radar this Week?

[ Issue Brief ] A Lost Opportunity to Reform the Censor Board, by Shrikrishna Upadhyaya

[ Podcast ] The Road Ahead for India and France ft. Sachin Kalbag and Yusuf Unjhawala

[ Opinion ] Data | The risk of small States’ heavy reliance on the Union government, by Sarthak Pradhan