#102 The US’ Options to Counter Chinese Legacy Chips

This edition is a cross-post of a paper written by Satya Sahu and Amit Kumar that asses the policy approaches available to the US to counter China's influence in the legacy chips supply chain.

— Satya Sahu and Amit Kumar

Introduction

Even as China has made satisfactory gains in developing its homegrown advanced semiconductor ecosystem, Beijing’s efforts are likely to face hindrances in the long term. However, China’s advances in capturing the market share of legacy or trailing-edge chips have sparked concerns in the US.

Legacy chips are semiconductors fabricated on mature nodes - 28 nm and above and are critical to the functioning of automobiles, power grids, industrial and medical equipment, military systems, navigation, IoT applications and several other consumer electronics. China harbours around 30% of the global mature node fabrication capacity behind Taiwan’s 49%. Projections estimate that Beijing’s share will increase to 39% by 2027. Further, reports indicate that China’s output of legacy chips soared by a massive 40% in the first quarter of 2024 - thrice the units produced in Q1 2019.

Several advantages could enable Beijing to emerge as the predominant player in the legacy chips domain. To begin with, the existing US export control measures do not restrict China’s access to mature fabrication technologies as they aren’t regarded as a national security threat.

Second, legacy or commodity chips are relatively cheap to produce as compared to advanced ones. This makes it easier for China to match capital investments against its competitors consistently. Also, profitability in this segment depends on shipping huge volumes, and trailing-edge foundries operate with razor-thin profit margins. Chinese companies are better equipped to capture this market. This is due to cost advantages stemming from economies of scale created by catering to a burgeoning domestic market and massive state subsidies. Other factors include robust backward supply chain linkages to essential inputs like materials and chemicals, etc.

Third, the Chinese have homegrown capabilities in mature node fabrication and are not heavily dependent on foreign support. This makes similar export restrictions an unviable option. Alternatively, import tariffs on Chinese legacy chips could massively raise the costs of intermediate components for downstream industries in the West. Therefore, sanctions and denial regimes to reduce dependence on Chinese legacy chips are unlikely to be effective either.

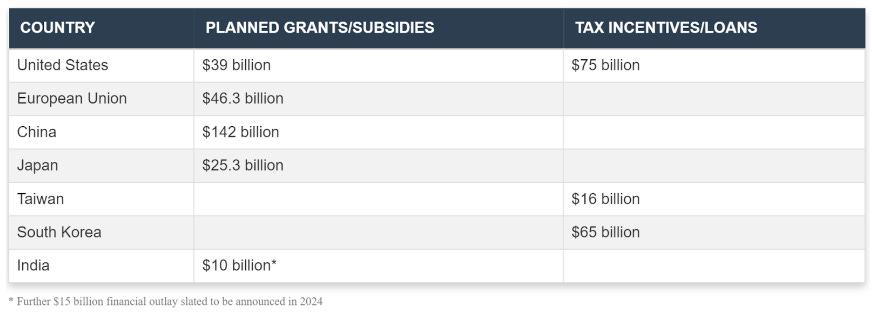

Finally, China’s Big Fund III plans to infuse US$ 47.5 billion into its semiconductor capabilities. With American attention largely focused on extending the capability gap vis-a-vis China in the advanced chip segment, extending the same level of attention to the legacy chip segment may prove costly.

Given this context, the most immediate danger that the US faces from China’s emerging dominance in the legacy chip value chain is the geoeconomic leverage it provides the latter against the former’s dominance in the value chain for advanced chips. Just as the US has used export controls on advanced chips to limit China's advancement in AI and military technologies, China could restrict legacy chip supplies to Western industries that rely on these components.

A significant percentage of Chinese legacy chip output is exported, which gives the buyers some countervailing leverage. Therefore, even though it does not constitute a strategic vulnerability, in the short term, this creates supply chain vulnerability for the US and its allies. The other long-term goal of the US would be to systematically reduce the risk of chip-based hardware backdoors and other supply chain risks in the legions of legacy chips used across critical infrastructure, defence equipment, and consumer electronics.

Assessing USA’s Options

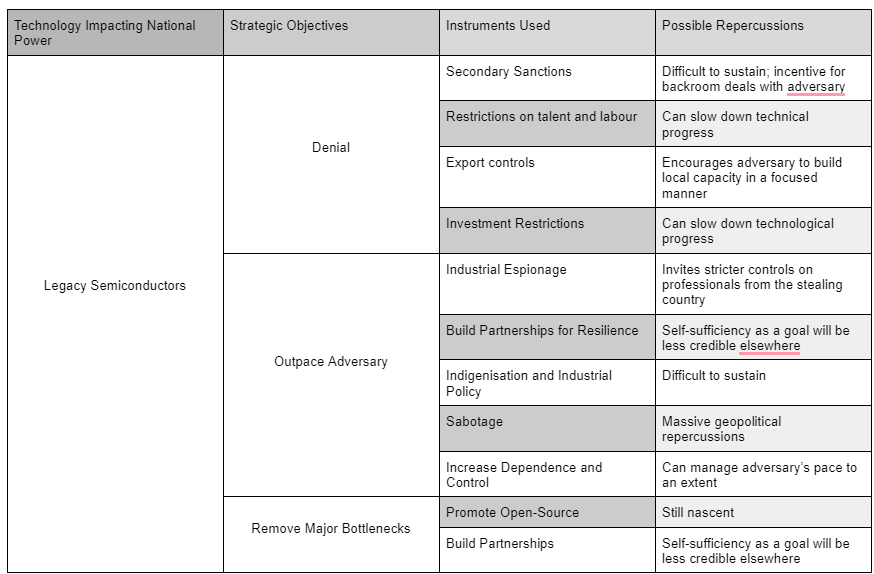

The following framework provides a useful lens through which to analyse the range of instruments available to the US to address its dependency on Chinese legacy chips, both in the short and long term.

Despite their nomenclature, “legacy” or “trailing-edge” semiconductor chips are also, if not more, meta-critical to innumerable critical and emerging technologies than “advanced” or “leading-edge” chips.

First, the US can either seek to deny or limit China’s access to certain technologies needed for producing legacy chips and to potential markets. However, as recent reportage on the current export controls on leading-edge chips indicates, a denial regime is difficult to sustain and can be circumvented.

As mentioned earlier, China's homegrown foundries like SMIC have developed strong internal capabilities in mature node chip fabrication that will not be heavily reliant on foreign assistance. Consequently, using export controls and sanctions similar to those on advanced chips and chipmaking equipment as part of a US denial strategy against China would likely prove ineffective.

Attempting to devote the same amount of focus and resources to duplicating this regime for legacy chip manufacturing capabilities will be very expensive and challenging to implement effectively over time. It would necessitate ongoing monitoring for smuggling and other diversion risks, as well as careful analysis of potential negative unintended consequences affecting its own industry.

Moreover, imposing import tariffs on Chinese legacy chips as an alternative approach could lead to significant cost increases for critical downstream industries (consumer electronics and automotive, for example) in Western countries that depend on these chips. This would negatively impact their cost competitiveness.

Therefore, neither extending export controls nor levying extensive tariffs will be a particularly useful policy tool for decreasing reliance on legacy chips from China. These options have significant drawbacks and limitations in their effectiveness.

Second, the US can focus its significant technological and economic resources on outpacing China in the legacy chip segment. However, consider that the October 2022 and 2023 export controls have (as the framework points out) provided a major impetus for Beijing to build local capacity in almost every segment of the semiconductor value chain. The recently announced Big Fund III plans to invest a further US$47.5 billion. The relatively lower cost of production and thin profit margins in this segment plays to the strengths of Chinese firms that benefit from the country’s comparatively lower labour costs and substantial government subsidies.

Continued financial injections, combined with the country's existing advantages in the legacy chip space, put China in a strong position to emerge as the preeminent player in this crucial segment of the semiconductor value chain. Again, the relative independence of Chinese legacy chipmaking capabilities from foreign assistance also makes it difficult for the US to deploy policy instruments that can effectively manage/slow down the former’s pace of development here.

While government subsidies are helpful, the economics of legacy chip production make it challenging for U.S. companies to compete on cost. At higher US production costs, domestic legacy chips would still be more expensive than Chinese ones. US buyers in cost-sensitive downstream industries would likely prefer to have the option to purchase technologically inferior but cheaper Chinese chips.

In the global market, US-made legacy chips would be even less competitive on price, as US companies face 30-45% higher manufacturing costs compared to the rest of the world. Even with subsidies absorbing initial capital costs, the US would struggle to match China's combination of low labour costs, massive state support, and the ability to scale production rapidly.

Many US chipmakers like Intel (and Taiwan’s TSMC) are focusing investments on current and future generation advanced process nodes (ranging from 10nm to 2nm), which could provide some degree of domestic resilience if China were to disrupt legacy chip supply suddenly. However, these facilities will still produce advanced, higher-margin chips (<12 or 7nm, their traditional comparative advantage).

Federal and state incentives also aim to promote leading-edge chip R&D and production. Pivoting to much older (>28nm) legacy chips at scale, therefore, is misaligned with the trajectory of the US chip industry. The US may be considering and even be prepared to absorb the costs of drastic large-scale decoupling from China when it comes to legacy chips. In the short term, subsidies and some level of domestic production may help tide over the disruption caused by Chinese restrictions. That, however, will not be economically sustainable for long.

Finally, the US has the option to remove major bottlenecks in the value chain for legacy chips, allowing it to achieve a more significant presence in it without needing to build massive local capacity. Acquiring this foothold will also enable Washington to establish and implement auditing mechanisms throughout the value chain to ensure the trustworthiness of the chips being procured.

Friendshoring as the Solution

The US possesses a significant strategic advantage over China through its extensive alliances and partnerships with geopolitically aligned countries (for instance, South Korea and Japan) that are key players across the semiconductor value chain. To effectively reduce reliance on China for legacy chip production in an economically sustainable manner, the U.S. should leverage these relationships to share the costs and risks of diversifying supply chains.

Each country has unique strengths in the semiconductor ecosystem, such as R&D, design (US, Taiwan), manufacturing (Taiwan, South Korea), or specialised equipment (Singapore, The Netherlands). The U.S. benefits from enabling these countries to optimise their respective comparative advantages to build legacy chip production capacity in an economically sustainable way.

In this light, friendshoring supply chains for legacy chips to like-minded countries emerges as the most feasible long-term solution. Vietnam, Malaysia, and India emerge as the primary contenders in the contest for reshoring. However, from the American perspective, India would appear to be the safest bet for four reasons.

Firstly, reshoring to Southeast Asian (SEA) countries is marred with challenges of keeping the supply chains resilient. Given that the port access of these countries opens into the South China Sea, which is increasingly susceptible to Chinese PLA aggressions, the Sea Lines of Communications (SLoCs) connecting the port facilities of SEA countries remain vulnerable.

Further, SEA countries have become increasingly reliant on Chinese trade, allowing the latter to possibly disrupt SEA-linked chip supply chains through economic coercion. Indian coastline and the Northern India Ocean, in this respect, are far more secure from Chinese aggression. Moreover, India is perhaps the most geopolitically aligned partner of the US among all the contenders, thereby limiting political risk. Thus, India’s geography and geopolitics make it a much more favourable contender for reshoring.

Secondly, India’s willingness to support chip manufacturing units through generous subsidies is a huge plus. The government’s current policy aims to provide upfront fiscal support of up to 50% of the project cost or capital expenditure across various categories (without making the contribution contingent upon production targets).

None of India’s geopolitical rivals in competition for US friendshoring have pledged comparable financial support. Given that India is willing to shoulder the significant upfront capital costs of setting up production facilities from scratch in the legacy segment, the US-led geopolitical West could feasibly accelerate India’s efforts to compete with China in producing competitive and affordable legacy chips for global markets. This frees up crucial resources for the US and its allies, which can then be directed towards sharpening their industrial policies to maintain their technological lead over China in developing cutting-edge semiconductor technologies.

Third, the Union government’s keen interest in supporting a domestically robust semiconductor ecosystem and direct oversight confers an added advantage of circumventing unnecessary bureaucratic delays, thereby ensuring the swift processing of viable projects.

For example, Micron's $2.75 billion semiconductor assembly and testing plant in Gujarat, which received swift approvals and substantial fiscal support from both the Union and state governments, broke ground within just three months of the initial announcement and is set to become operational by late 2024. Similarly, Apple and its contract manufacturers have significantly benefited from the $4.66 billion production-linked incentives scheme for mobile devices, leading to a doubling of iPhone exports from India to $12.1 billion in FY 2023-24 and the company capturing nearly 50% of Indian smartphone exports in Q2 2023.

Lastly, India’s cost advantages in labour combined with upstream linkages to its large pool of skilled chip design and engineering talent and downstream linkages to multiple slated assembly and packaging facilities will ensure that global clients looking for end-to-end services for their legacy chip requirements will find an entire ecosystem that can cater to their needs.

Average labour wages in India are already the lowest among the China+1 alternatives. For instance, in 2023, average labour wages in India (USD 196) were less than 2022 wage rates in the Philippines (USD 278), Vietnam (USD 323), Thailand (USD 458), Malaysia (USD 605) and China (USD 1208). Incidentally, India’s wage rates in 2023 were comparable to that of China’s wage rates in 2000 (USD 150).

Potential Remedies

While the US and its allies are considering gradually cutting down on legacy chip imports from China over the next few years, there are a few ways in which the US could help accelerate India’s journey to become a chip fabrication hub. These can be undertaken as part of the Initiative on Critical and Emerging Technologies (iCET) and the MoU on Semiconductor Supply Chain and Innovation Partnership.

On the demand side of things, establishing an incentive program for US chip companies and OEMs to source their required legacy chips from India-based production facilities would be an excellent first step.

A mix of executive action or legislation providing tax credits or other financial benefits tied to the use of Indian-made chips would create an assured market for newly operational Indian chip manufacturers. This, along with the demand from India’s own burgeoning market for legacy chips, will help accelerate the iteration and innovation process needed for Indian foundries to become better at chip manufacturing.

Alongside this, the US government can provide guidance to India-based foundries to establish best practices, standards and processes that can enable them to be designated as “trusted sources” of semiconductors.

The CHIPS Act itself has allocated $500 Million to the Department of State to create the International Technology Security and Innovation (ITSI) Fund to “coordinate with foreign-government patterns on semiconductor supply chain security”. As of September 2024, the Department of State has partnered with the India Semiconductor MIssion through the ITSI fund and will initially conduct a comprehensive assessment of India’s extant semiconductor ecosystem and its workforce and infrastructure needs. This collaboration can begin with a focus on identifying and building capacity for chips relevant in a narrow range of critical sectors such as defence (which can be done based on requirements set by the CHIPS Program Office for “secure and assured microelectronics”).

Further, the US could also ensure that imported Indian-made legacy chips are a duty-free product category by restoring India’s status as a beneficiary of the Generalised System of Preferences (GSP) program. The erstwhile Trump administration revoked India’s status in 2019 on grounds of non-reciprocity in market access. Renewed negotiations between both governments on this front and reinstatement of GSP eligibility for duty-free treatment of chips would create additional incentives for US OEMs to prefer sourcing from Indian fabs.

In addition to demand-side incentives, supply-side support from the US could take the form of low-interest loans or loan guarantees to domestic firms interested in helping build India’s legacy chip foundries or other segments of its semiconductor ecosystem (such as for the provision of materials, chemicals and gases to Fabrication and Outsourced Assembly and Testing facilities).

Taking a leaf out of the Quad’s trilateral Supply Chain Resiliency Initiative (between India, Japan, and Australia), the US could also do much to promote technology and policy coordination between India and other allies like South Korea and Taiwan. Advocating for India’s inclusion in plurilateral semiconductor supply chain initiatives like the “Chip 4” alliance, involving the above countries, would help align trade policies, address regulatory barriers, and industry collaboration along the entire breadth of the legacy chip value chain.

This would possibly reduce the time needed for India’s semiconductor ecosystem to become technologically competitive vis-a-vis China (ensuring that Western buyers of these chips get quality chips at competitive prices).

To recap, whilst the US seeks to curb China's growing dominance in the legacy chip segment, it must also realise that the opportunity cost of building indigenous capacity is prohibitively high. Instead, the US would find far better value for money and resilience in its supply chains by supporting India's journey to become a global legacy chip hub. India's generous incentives, geopolitical alignment, cost advantages, and robust linkages to other segments of the semiconductor ecosystem make it an ideal partner.

What We're Reading (or Listening to)

[Opinion] India Must Match China’s Speedy Moves in Bangladesh’s New Political Landscape by Rakshith Shetty

[Podcast] Will synthetic biology produce the next pandemic? By Aditya Ramanathan and Shambhavi Naik

[Takshashila Issue Brief] Implications for India from West Asia’s War, by Aditya Ramanathan and Adya Madhavan