Cyberpolitik #1: China’s actions create common ground for cooperation

— Aditya Pareek

China does not shrink from using asymmetric means to achieve its political and geostrategic goals. Cybersecurity is an important emergent asymmetric domain where Chinese, North Korean and Russian grey zone activities have inflicted considerable damage.

Japan finds itself an adversary of China ,North Korea and at least less than an ally to Russia.

Cyberattack on JAXA involved the PLA SSF and a CCP Member

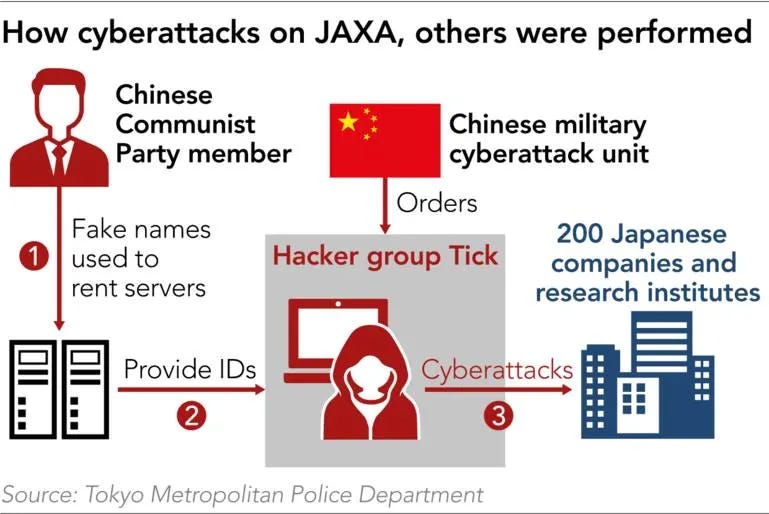

According to this report in Nikkei, Japan recently found itself on the receiving end of cyberattacks that targeted Japan’s space agency JAXA between 2017-2019. The Tokyo Police Department attributes the attacks to a “Chinese IT systems engineer who is also a member of the Chinese Communist Party”. Tokyo Police also believes that the perpetrator registered web servers under a false name in Japan to carry out the attack and that he likely had the aid of China’s People's Liberation Army. During a press conference the Commissioner-General of Tokyo Police specifically mentioned a Chinese hacker group called “Tick” and the PLA’s Strategic Support Force(SSF)’s Unit 61419.

The attackers are believed to have used malware that was enabled by a zero-day exploit. A zero-day exploit amounts to the attacker utilising previously undiscovered and unpatched vulnerabilities in the security of target systems to gain access to secured areas. Once in, the attacker can install malware, alter or steal login credentials or information on the target systems and even possibly sabotage them.

New Japanese Cybersecurity Strategy is in the making

Another recent report in Nikkei mentions that the Japanese government is preparing a new cybersecurity strategy to safeguard critical infrastructure, in light of attacks in various countries.

According to Japan’s chief cabinet secretary Katsunobu Kato, who is incharge of formulating the strategy, the main points were deliberated and summarised in a recent meeting held at Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s office. The Japanese cabinet is likely to approve it in fall 2021. The strategy will be the primary cybersecurity guidance to Japan’s functionaries for at least the next three years.

India’s ISRO has also been subject to Cyberattacks from China and North Korea

China and North Korea have both targeted ISRO with cyberattacks on various occasions. ISRO maintains that none of these cyberattacks have jeopardized the sanctity of its data or had an adverse effect on any of its operations or major assets.

With cybersecurity emerging as an important domain, Indo-Japanese co-operation can be furthered in the Quad framework

It is interesting to note that India and Japan last year discussed and finalised the text of a major bilateral cybersecurity co-operation agreement but are yet to sign it. During a recent meeting of the Quad, the focus was on cybersecurity as well as semiconductor supplies, since supply chain dependencies carry their own risks.

In an opinion piece in Outlook Dr. Jaijit Bhattacharya, President, Centre for Digital Economy and Policy Research, advocates cybersecurity cooperation between Quad states. Bhattacharya uses an analogy of neuron connectivity in the human body to explain the importance of digital connectivity for a country.

Another interesting point he highlights is the folly of believing an “air-gap” will save critical systems from cyber-sabotage. An “air-gap” in cybersecurity refers to the lack of any internet connectivity on the critical system.

Dr. Bhattacharya quotes the example of the 2010 cyberattack on Iranian nuclear centrifuges, which were not connected to the internet either but were reportedly sabotaged by malware inserted via a physical USB flash drive on an “air-gap” secured local system.

In conclusion Dr. Bhattacharya postulates that “Australia too has the institutional structures required to build an international cybersecurity alliance. It is a similar story with the US and Japan also”.

The Fog of Tech War: China-US tech war and implications for India

— Pranay Kotasthane

I spoke with Nirmala Ganapathy from the Strait Times on the implications of the China-US tech war on India. My responses to three key questions were as follows:

Q: Do you see Chinese firms maintaining their edge in many sectors?

No, I don't see Chinese firms being treated the way they were until a couple of years ago.

Every Chinese company and investment is now seen from a strategic lens rather than a purely economic one. What this means is that Chinese companies will continue to face more scrutiny in technology areas that have longer lock-in periods or need agreement with Chinese standards. For example, a couple of days ago, India released a list of companies participating in 5G trials — a list that had no Chinese companies. Chinese companies might continue to maintain their edge in the less-controversial areas such as physical infrastructure, electrical machinery etc.

Q: The China-US tech war and how it will benefit India

The greatest benefit of this tech war is the acknowledgement by other countries that the only way to overcome the China challenge is if they provide better alternatives themselves. Very often, this requires multilateral or bilateral cooperation and therein lies the opportunity for India. The Quad Working Group on Critical and Emerging Technologies is a good example of this trend where the four countries are now willing to coordinate on technology standards development, principles on technology design, and critical technology supply chains.

Q: Why is the Indian market important for both countries?

Apart from the potential of the huge end-consumer base, India also has a formidable producer base. India affords technology companies the opportunity for cutting-edge technology development. Take the example of semiconductors. Except Apple, virtually every notable semiconductor company has a development or R&D centre in India. That's because India has a large talent pool of chip designers. This also holds true for other software development.

Internet Ka Boss: One earth, many internets

— Prateek Waghre

Whether it is the Indian state's renewed face-off with Twitter, or Russian threats to throttle Google's traffic - such events always raise questions about models of internet governance and power balance (or imbalance) between various participants.

In 'Four Internets' Kieron O’Hara and Wendy Hall identified five types of digital governance models; Silicon Valley's Open Internet driven by technology; Brussel's Bourgeois Internet with its focus on peace, prosperity and cohesion through rules; Beijing's Authoritarian Internet with its emphasis on control and surveillance; and Washington DC's Commercial Internet, which places the interest of private actors at the center. Moscow's spoiler model exploiting an open, decentralised internet is featured as an addendum.

Eighteen months later, in India, Jio, and the Four Internets, Ben Thompson highlights an 'increased splintering in the non-China model' with a 'U.S. Model' (similar to a combination of O'Hara and Hall's open and commercial internets), a European model (similar to the bourgeois internet), and an Indian model characterised by 'unencumbered' foreign participation in 'digital goods' and a 'tighter leash' over the physical layer. Jack Balkin's 2018 essay 'Free Speech is a triangle' depicted dyadic interactions between states, corporations and societies and their interactions via an inverted triangle. The ability to speak is an outcome of the power struggle between these participants.

A recent paper by Demos provides a framework to visualise these models and relative power. It identifies four powers that will shape the rules governing the internet - states, corporations, individuals and machines with each of them enjoying some degree of control/power.

These models do not exist in a vacuum, the reality of the internet as a 'network of networks' and a 'borderless entity' also implies each model and its four powers will interact with other models/powers and influence them. Though such models are not a perfect representation of reality, they provide useful frameworks to think about the future of the internet.

Cyberpolitik #2: Disentangling Civilian & Cyber infrastructure

— Suchir Kalra

Cyber attacks inflicted costs on India during the China-India LAC standoff in 2020. As can be seen in a report published by Insikt Group, the power sector victims of the Red Echo Cyber Attacks were spread all over India.

This not only created additional costs for the power sector firms, but the long power cut on October 12th last year could have potentially led to losses of lives in small hospitals where patients were struggling without regular ventilator supplies. Mainly, Mumbai experienced an extremely long power outage , with the railways systems halted and transport servers supposedly hacked. A long power cut of this intensity might have led to hindrances in the COVID-19 healthcare management. Whether any lives were lost due to the cyber attack is still uncertain, however the potential inconveniences and hurdles that civilians likely faced were undoubtedly severe. Though the government has not clearly admitted this was cyber sabotage, other reports speculate that there is a link between the Mumbai power outage and the RedEcho Cyber attack but it still “remains unsubstantiated”. However, the recently released February 2021 report by Insikt confirms the “coordinated targeting load dispatch centres” and other network access.

The Github repository (screenshot below) released by the Insikt Group additionally shows some of the indicators of the Red Echo Attacks, which mentions keywords such as “Ship”, “Railway” etc, suggesting the targets of Red Echo. These keywords notably link to various elements of the civilian infrastructure.

This is not the first time, nor the last

The first iteration of the internet was created for military purposes in 1969 , known as the “Arpanet”. It soon evolved into the internet as we know it now. The internet has overlaps between military and non-military(civilian) infrastructure even today. Thus, an attack such as Red Echo, which might have started by targeting military assets, can easily and conveniently spread into something that is causing civilian harm. It’s possible to argue that such attacks violate International Humanitarian Law (IHL).

Therefore, researchers Robin Geiß and Henning Lahmann have often argued that there is a major need for a “Disentangling of military and civilian cyber infrastructure”, where they explicitly lay out strategies and policy framework amendments that need to be implemented to ensure a safer cyber space for both the military and civilians. To quote from one of the strategies that they put forth in their paper on Cyber Warfare in 2012:

“..at least certain highly sensitive civilian networks and infrastructure pillars, the functionality of which is essential for the civilian population, could be physically removed and disconnected from other networks and the general cyber infrastructure.”

— (Pg 392, CYBER WARFARE: APPLYING THE PRINCIPLE OF DISTINCTION IN AN INTERCONNECTED SPACE).

They also propose the creation of digital safe havens, which are dedicated civilian spaces similar to demilitarised zones. Overall, in gist, the researchers Geiß and Lahmann are trying to reiterate the urgent need for a disaggregation between the military and civilian cyber spaces, failing which there could be dire consequences.

Our Reading Menu

The geopolitics of ‘platforms’: the TikTok challenge - Internet Policy Review

The Geopolitics of Deep Oceans - Book covering the geo strategic dimension of oceanography

Singularity University has put out a paper on algorithmic bias -https://go.su.org/algorithmic-bias-preview

Cyber Deterrence is Overrated by Matthias Schulz

Is Cyber Deterrence Possible? by Timothy McKenzie

Exposing One of China’s Cyber Espionage Units by Mandiant

Stateless Attribution Toward International Accountability in Cyberspace by John S. Davis and others

Non-proliferation Regime for Cyber Weapons. A Tentative Study by Cristian Barbieri, and others

On Netwars by Jeffrey Barlow