** A modified version of this post was published on Firstpost here and was cross-posted from the Takshashila Institution’s blog series.**

The India Semiconductor Mission’s (ISM) ambitious goal to establish a robust domestic chip design and manufacturing ecosystem is gradually achieving fruition. The Union government recently approved three semiconductor units, including India’s first fabrication plant by Tata Electronics Private Limited, in partnership with Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation in Dholera, Gujarat.

Foundation stone laying ceremony of the TATA-PSMC fab project (Source: The Indian Express)

India’s presence in the chip design stage of the global value chain (GVC) is sizeable and well-established, playing host to global semiconductor design houses such as AMD and Qualcomm. There’s a slight glitch in the matrix, though: despite a large pool of skilled design engineers and a growing domestic market, India has struggled to establish a robust homegrown chip design and product ecosystem.

New Delhi has launched initiatives like the semiconductor Design-Linked Incentive (DLI) and Chips 2 Startup (C2S) schemes, which aim to provide select startups and universities with affordable access to Electronic Design Automation (EDA) software tools essential for designing all modern chips. (We have previously written about the issues surrounding the extant version of the DLI scheme here.)

However, a key hurdle for startups and academia is the lack of standardised and affordable access to collaborative research facilities and critical chip design toolkits inextricably linked to the fabrication stage of the supply chain that India is focused on: Process Development Toolkits (PDKs).

Figure 1: Different elements of a PDK (Source: Cadence)

A PDK is essentially a suite of files, libraries, and documentation provided by a semiconductor fabrication facility that contains detailed information about the manufacturing process, rules for design, models, and other technical specifications required to reliably design millions of chips.

Consider these as standardised building blocks adhering to the manufacturing constraints and capabilities of a foundry’s specific process node (130nm, 65nm, etc.), which designers use to construct more complex chip layouts. Adhering to these rules is critical for fabless firms to achieve high yields and reliability in the final manufactured chips.

Foundries worldwide invest significant resources in developing and optimising their manufacturing processes. Their PDKs contain sensitive and proprietary information, so they are closely guarded and provided only to design firms under strict non-disclosure requirements and hefty licensing fees.

The proprietary nature of PDKs has some obvious drawbacks for a nascent industry and for academia’s efforts to cultivate homegrown talent. It adds to the high costs of chip design and can create entry barriers for smaller design firms and startups who may not have the resources or relationships to access PDKs from commercial fabs.

Just designing a chip from scratch for a mature 65nm node alone costs almost $25 to 30 million. This can also limit collaboration and innovation in the design ecosystem, as designers are restricted in their ability to iterate and build upon each other’s work if the prior work relied upon a specific fab’s PDK. In academic institutions, students may study the theoretical foundations of advanced chip design but not gain practical expertise in manufacturable process flows that would make them valuable talent for design and fabrication facilities worldwide.

Proprietary/closed-source PDKs are a stumbling block for the proliferation of open-source hardware, as well as for the open-source community and researchers that develop accompanying EDA tools for such silicon. They pose a security question because countries want to ensure that chips for strategic and military purposes are sourced from trusted foundries; not being able to audit the code determining the layout of those chips is a potential vulnerability, as it could be an avenue for inserting hardware backdoors.

Industry and academia worldwide have recognised these drawbacks, and some recent efforts to develop open-source PDKs are underway. SkyWater Open Source PDK, for example, was released in 2020 as a collaboration between Google and SkyWater Technology Foundry. It aims to provide anyone with free access to a manufacturable PDK for SkyWater’s 130nm process. Open source initiatives like this and Germany’s IHP Open PDK have begun widening access to chip design by providing low-cost entry points to students, researchers, and small startups.

India’s existing semiconductor research facilities in academic institutions like the Indian Institute of Science’s (IISc) National Nanofabrication Centre, the Indian Institute of Technology, Bombay’s (IIT-B) Nanofabrication facility, and the state-owned Semiconductor Research Laboratory (SCL) could provide startups and researchers everywhere with open access to their PDKs. Inexplicably, this has not happened.

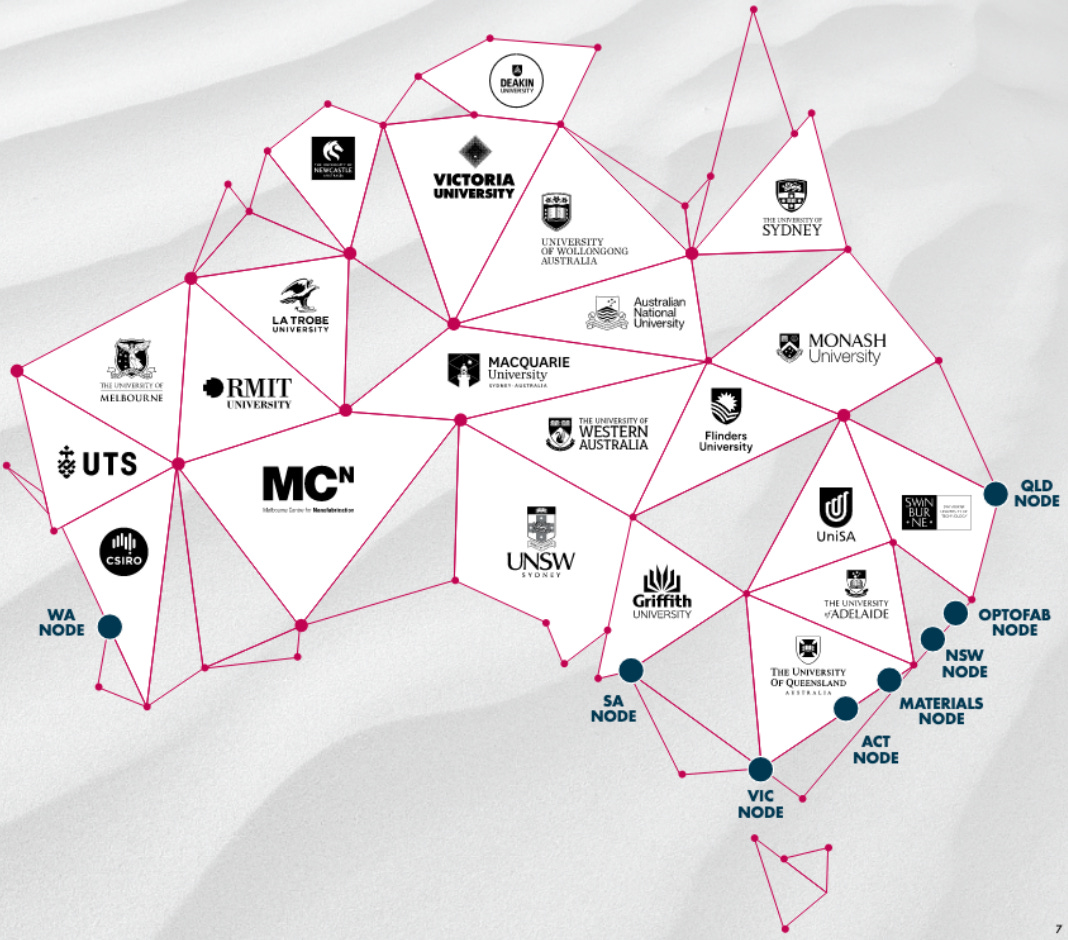

A potential open and collaborative model is Australia’s National Fabrication Facility and the Canadian CMC Microsystems.

Figure 2: ANFF has 8 Nodes spread across 21 institutions.

Like IISc and IIT-B, Australia’s National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) also has state-of-the-art tooling and characterisation facilities. While it does not open-source its PDKs, it provides open access to its specialised fabrication and research facilities for prototyping, skill development, and training to all Australian researchers and industry clients for a fee. Similarly, Canada’s CMC Microsystems is a non-profit that provides shared access to state-of-the-art design tools, prototype fabrication, testing capabilities, and expertise to researchers and industry worldwide via its National Design Network.

Figure 3: Source - CMC’s Annual Report (2022-23)

CMC provides EDA tools and open-source PDKs to Canadian clients but also couples those with subsidised access to fabrication services through eight different partner foundries worldwide.

An equivalent model in India could function as a hub-and-spoke network with institutions like IISc and IIT-B functioning similarly to ANFF’s nodes, offering open access to research facilities and R&D fabs (with open-source PDKs) to Indian researchers and industry. A consortium of such institutions could aggregate client designs and manage the fabrication process with SCL functioning as the foundry hub of the model. The union government's recently unveiled INR 10,000cr plan to invest in SCL to transform it into an R&D centre could make this model a reality. Taking a page out of CMC's book, this model could look towards onboarding more trusted foundries from friendly countries like Singapore.

This effort can be subsidised under an existing or new ISM initiative or the recently announced Indian Semiconductor Research Centre.

Such a model would accelerate semiconductor product development in India. It would enable researchers to verify novel concepts, startups to reduce time to market, and students to gain hands-on experience in manufacturable chip design—all while fostering a sorely needed culture of collaboration and innovation.

**Satya and Pranay are researchers with the High-Tech Geopolitics programme at the Takshashila Institution, Bangalore. For the latest research updates from Takshashila Institution, visit https://takshashila.org.in/**

PDK is an IP. I don't see any incentive for companies to make it open source.